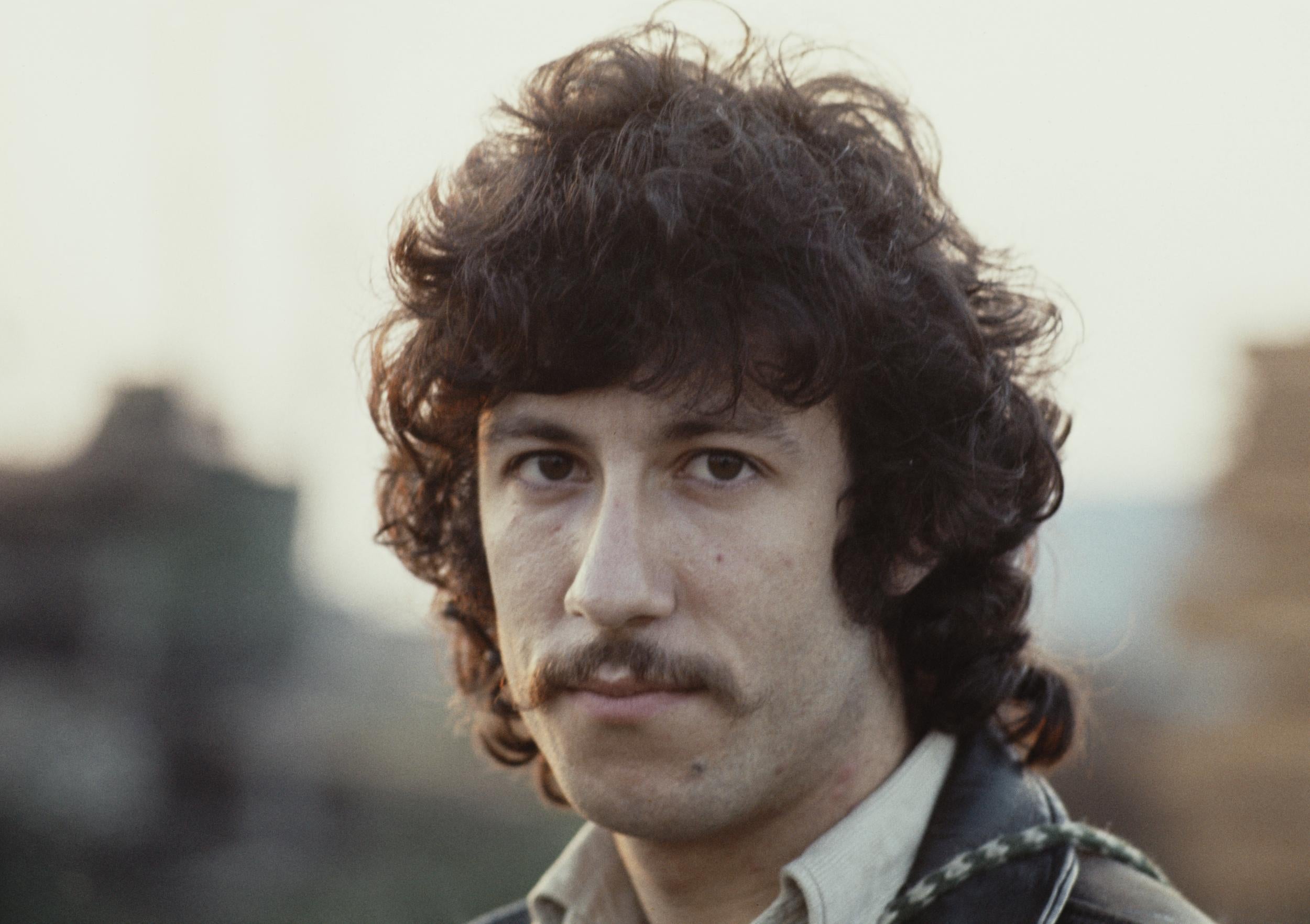

Peter Green: Sixties guitar hero and co-founder of Fleetwood Mac

His early leadership of the group was so powerful that, when they released their first album in 1968, the record label billed it as ‘Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Peter Green was a founder of Fleetwood Mac and was considered one of the greatest guitarists of his era before becoming a tragic casualty of the rock world, beset by drug problems and mental illness.

He has died at the age of 73. Swan Turton, a law firm representing his family, announced the death in a statement. Further information, including the exact date, place and cause of death, was not released.

Green was revered as perhaps the finest rock guitarist of his generation, ranked on the same level as Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page.

He was a charismatic figure at the forefront of a fast-moving rock-and-roll revolution, as the music evolved in the late 1960s from its blues-based origins to a more ornate and theatrical style, with overtones of spiritual striving.

He replaced Clapton in one of the seminal British groups of the time, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, and in 1967 was a co-founder of Fleetwood Mac. Green named the band after two of its members – drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie – but at the beginning, he was its undisputed leader and creative dynamo. The music press dubbed him the “Green god”.

“Peter could have been the stereotypical superstar guitar player and control freak,” Fleetwood told The Irish Times in 2017. “But that wasn’t his style. He named the band after the bass player and drummer. The reason there’s a Fleetwood Mac at all is because of him.”

Rolling Stone magazine named Green one of the top 100 guitarists in rock history. One of his idols, Delta blues master BB King, reportedly said Green “has the sweetest tone I ever heard. He was the only one who gave me the cold sweats.”

Green’s early leadership of Fleetwood Mac was so powerful that, when the group released its first album in 1968, the record label billed it as “Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac”. In addition to classic blues tunes by Robert Johnson and Elmore James, the album contained five songs by Green and three by its second guitarist, Jeremy Spencer. (A third guitarist, Danny Kirwan, later joined the group.)

Two other albums, Mr Wonderful and Then Play On, followed in 1968 and 1969, respectively, both featuring Green’s compositions, singing and guitar wizardry. Music polls in Britain rated Fleetwood Mac ahead of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones.

Some of Green’s most dazzling work, however, could not be heard on the band’s first albums. “Black Magic Woman” was released in 1968 as a 45-rpm single and appeared on a 1969 compilation album before becoming a hit for Santana in 1970.

Green’s lyrical instrumental ballad “Albatross”, also from 1968, became a No 1 hit on the strength of his sublimely controlled touch on his Les Paul guitar. His 1969 song “Oh Well”, which reached No 2, opened with Green’s snarling electric guitar riff and an unforgettable opening line:

Can’t help about the shape I’m in

I can’t sing, I ain’t pretty and my legs are thin

But don’t ask me what I think of you

I might not give the answer that you want me to.

After rocking out for more than two minutes, the band dramatically shifted to an elegant, cinematic mode in the second half of the song, with Green playing an almost mournful extended solo on an acoustic Spanish-style guitar, with echoes of Andres Segovia.

His final major contribution to the Fleetwood Mac canon came in 1970, with “The Green Manalishi”, a song about the evils of money that contained menacing lyrics – “The night is so black that the darkness cooks” – and even more menacing guitar lines.

During his time with Fleetwood Mac, Green grew more eccentric in his manner and dress, sometimes performing in robes, with a large cross around his neck. His experiments with hallucinogenic drugs came to a head during a European tour in March 1970, when the band arrived in Munich.

Green was met at the airport by a mysterious couple – a young woman in wire-rim glasses and a man wearing a cape. He ended up spending several days with the couple, apparently taking LSD at a castle outside Munich. When other band members tried to retrieve Green from what they described as a cult, they found him playing guitar in a frenzied fashion.

Even before then, his songs were becoming more apocalyptic, and he had implored his bandmates to give away their money and other material possessions. Fleetwood and McVie persuaded Green to rejoin the band, but he left after two months.

“To this day,” Fleetwood said in 1996, “John [McVie] and I always say that was it. Peter Green was never the same after that.” Kirwan, Green’s fellow guitarist in the band, also took hallucinogens at the German castle, and his behaviour soon became so erratic that he was forced out of the group.

Green briefly played with Fleetwood Mac in 1971, but refused to sing, then quit the band for good. He gave away his royalties, sold his guitars and began staying with friends and on doorsteps.

During the 1970s, he worked at a petrol station, as a hospital attendant and as a gravedigger. In 1977, after he was arrested for threatening his accountant with a shotgun, Green was treated at a psychiatric hospital.

Meanwhile, he made a few solo records that went nowhere. In the late 1970s, Fleetwood arranged a record deal for Green that would have earned him nearly $1m for a series of albums. At the last minute, Green refused to sign the contract.

He vanished into silence and continued treatment for mental illness. He had a short-lived marriage in the 1970s, then later lived with members of his family. His fingernails grew so long that he could not finger the chords on a guitar.

By 1995, Green was staying in the English countryside with old friends, including musician Nigel Watson. When Watson handed Green a guitar, it was the first time he had touched the instrument in a dozen years.

Slowly, some of his old facility returned. In the late 1990s, Green started a new band, called the Splinter Group. He recorded an acoustic album, The Robert Johnson Songbook, in 1998, and a few other albums.

He went on low-key tours of Europe and the United States, looking nothing like his old self. Once slender, with dark, curly hair and a moustache, he had become bald, clean-shaven and portly. He often strummed rhythm guitar while others performed the majestic solos he had been known for in earlier years.

In interviews, he was gentle, self-effacing and rambling.

“I was very critically ill for a while there, you might say,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1998. “I’m not really back yet.”

Peter Allen Greenbaum was born on 29 October 1946 in London. His father was a tailor who later worked for the postal service. The family adopted the name Green in the late 1940s.

While growing up in a working-class area, Green was often subjected to antisemitic taunts. He became engrossed in music at age 10, after an older brother brought home a guitar.

By 15, Green had left school to become an apprentice butcher, but his real focus was on music, inspired by blues and early rock and roll. He played bass and guitar in several bands before joining Mayall’s Bluesbreakers in 1966. A year later, with Mayall’s blessing, Green invited Fleetwood and later McVie to leave the Bluesbreakers and form Fleetwood Mac.

Over the years, Fleetwood Mac changed personnel and their musical style, becoming more of a pop-oriented band with two female singers, Stevie Nicks and Christine McVie. They became one of the most successful groups of the 1970s and 1980s, selling more than 100 million records. When Fleetwood Mac was named in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1998, Green was present for the ceremony but did not perform.

Survivors include a daughter from his marriage to Jane Samuels, which ended in divorce, and a son from another relationship.

For years, Green remained a subject of enduring mystery and tragedy. He seemed to be a cautionary tale of the rock-and-roll life, like the burnout cases of Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett or the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson.

Musician and writer Martin Celmins published a biography of Green in 2003, and the BBC produced a documentary about his life in 2009.

After 2010, Green stopped performing in public. When Mick Fleetwood produced a star-studded London tribute concert in Green’s honour in February, he did not attend.

“I’ve been kind of dead for a long time,” Green said in 1998. “I couldn’t function at all. I really haven’t got it all together yet, but I’m working on it. I certainly feel a lot better when I play music, however.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments