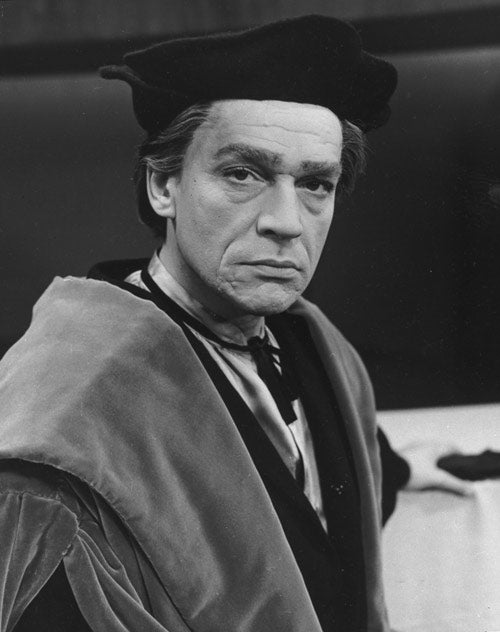

Paul Scofield: Oscar-winning actor whose phenomenal range was unmatched in his generation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."It isn't difficult to leave King Lear or Macbeth", reflected Paul Scofield late in his career, adding "but once you have gone back to yourself, you want it to be the same self you have always been".

Scofield happily accepted a CBE ("an honour with a hint of hard work about it"), but declined a knighthood. This was fundamental to one who shunned the flim-flam of fame – even when international stardom came his way with the film A Man for All Seasons. He enjoyed a profoundly happy marriage to Joy Parker – they met as young actors – for more than six decades, and for most of his life remained in the Sussex village where he had been born.

Even a brief selection of the roles tackled by Scofield indicates a phenomenal range, unmatched by any other great actor of his era. In several of those parts – Hamlet and Lear (under Peter Brook, the director with whom he was most crucially associated), Timon and Borkman – Scofield was supreme. He excelled at riven men, or when playing two men simultaneously (the twins of Ring Round the Moon or, on television, both upright old Martin and malign Antony, the Chuzzlewitt brothers in Martin Chuzzlewitt). These "double" roles seemed to liberate Scofield to reach the highest planes of acting; especially dazzling was his Khlestakov, the shabby-genteel clerk spiralling into self-mythism in the mistaken identity of Gogol's The Government Inspector (Aldwych, 1966).

Discovering at an early age his love of acting – as a schoolboy Juliet he divined a turning-point in his life "because thenceforward there was nothing else I wanted to do" – he never deviated from the kind of actor he aimed to be:

I enjoy the loss of myself, of discovering a writer's human creation . . . Effective acting wasn't what I wanted to do. I didn't want to make effects; I wanted . . . to leave an impression of a particular kind of human being.

This was the deepest Scofield would go into analysis of the alchemy of his secret art, that sense of mystery which informed many of his "particular human beings" with their special nimbus.

Scofield's Sussex childhood was happy but somewhat bifurcated; his mother was a Catholic and his father's headmastership of Hurstpierpoint's Church school meant "some days we were little Protestants and on others devout little Catholics" – and his father was "sir" at school and "dad" at home.

Leaving school at 17 Scofield trained briefly at the Croydon Rep – crossed toes (later used to considerable effect for several distinctive stage walks) exempted him from call-up – and at the London Mask Centre, where Eileen Thorndike spotted his gift. She took him into her semi-professional company in Bideford, Devon, where he was soon being cast in leading parts.

During a period based mostly in Birmingham, Scofield worked for the Travelling Repertory Company under Basil C. Langton, a saturnine Canadian who cast Scofield as Horatio in Hamlet (Joy Parker played Ophelia), Sergius in Arms and the Man (Birmingham, 1942), and, in London, as a heroic young miner in John Steinbeck's The Moon is Down (Westminster, 1943).

Birmingham saw the earliest Scofield glory years when Sir Barry Jackson, one of the theatre's great talent-spotters, brought him into the company at the Birmingham Rep at the start of its revival as the country's leading regional house. The company's directors included the wunderkind Peter Brook, at 20 already displaying precociously dazzling invention.

Scofield played a much-praised Tanner in Man and Superman (Birmingham, 1945) for Brook, who worked with him on his demanding speeches, infusing them with the authentically Shavian bristling energy; the Scofield voice, dark velvet with an arresting rift and stamped by a ringing upper register, was already unmistakable.

When Jackson took over the Stratford Memorial Theatre he took Scofield and Brook with him. For Love's Labour's Lost (1946) Watteau was Brook's inspiration for a romantic landscape of stately parks; Don Armado was played by a Scofield, who gave an astonishingly mature tragi-comic portrayal of meditative detachment (he was compared with "a beautiful old borzoi").

For some, even more memorable than Armado, was the following season's Mephistopheles in Marlowe's Doctor Faustus (1949); Scofield's quiet delivery of: "Why, Faustus, this is hell, nor are we out of it" breathed the torments of eternity, freezing the blood. Back with Brook he tackled Mercutio in a controversial Romeo and Juliet (1947) – the director threw out most of the scenery during a dress-rehearsal to create a sun-baked "empty space" – giving another revelatory portrayal. He delivered the "Queen Mab" speech lying on his back; it was described by Peter Ustinov as sounding "like an elusive nocturne from a man who didn't like to be referred to as a poet, talking in his sleep".

A third Stratford season gave him the chance to give his first Prince in Hamlet (1948). J. C. Trewin, most trustworthy of Hamlet-spotters (85 covered in his critical career), noted perceptively: "I have not met a performance less externalised, able to communicate suffering without emotional pitch and toss; he had that within which passeth show." This performance mined the pathos of Hamlet as spiritual fugitive.

The powerful commercial management H.M. Tennent under Hugh ("Binkie") Beaumont cast him in the leading role of Alexander the Great in Terence Rattigan's Adventure Story (St James, 1949), but his big West End breakthrough came with his twin turn as faithless Hugo and modest Frederick in Fry's version of Jean Anouilh, Ring Round the Moon (Aldwych, 1949) with Brook directing in a Oliver Messel set, perfectly pitched for a particular public hungry for romantic escapism (it ran for two years).

An admirer of John Gielgud, Scofield jumped at the chance to play Don Pedro – wryly contemplative – in a remounting of Gielgud's famous production of Much Ado About Nothing (Phoenix, 1952) to Gielgud's Benedick, and was keen to rejoin Gielgud and Brook for a Lyric, Hammersmith season in 1952/3.

Inevitably perhaps, Scofield's King in Richard II (1952) directed by Gielgud, the outstanding Richard of his generation, was distinctly constrained; chillier, perhaps, than usually played, this Richard impressed most in the earlier episodes. Gielgud also directed him as a hilariously self-absorbed Witwood in The Way of the World (1953), but the glory of the season was Brook's chiaroscuro revival of Otway's Venice Preserv'd (1953) with Gielgud and Scofield thrillingly matched as the conspirators Jaffeir and Pierre.

Now a box-office star, in Wynyard Browne's A Question of Fact (Piccadilly, 1953), a slow-burn study of hereditary insanity, Scofield headed a remarkable cast including Gladys Cooper and Pamela Brown for a long run. He combined this with his first movie role, playing Philip II of Spain opposite an eye-patched Olivia de Havilland as the Princess of Eboli in That Lady (1954), a performance of careworn majesty, perfectly scaled for the camera's ruthless perception of thought. The rushes had 20th Century-Fox's Darryl Zanuck insist that Scofield's part be built up ("we can make him a real star").

A second Hamlet (1955), directed by Brook, was part of a 1955/6 Phoenix Theatre season and also visited Moscow. Again Scofield, with his usually unerring hot-line to the audience, pierced directly to the heart, perceptibly finding more irony in the role. Brook worried while Hamlet was playing during rehearsals for The Power and the Glory (1956), adapted from Graham Greene's novel, that his star might not be ready in time. Scofield remained unruffled, closed in Hamlet on a Saturday, had his hair cut ruthlessly en brosse on the Sunday and made Brook and the production team gasp when he stepped on to the stage at the Theatre Royal, Brighton for the Monday dress-rehearsal of the pre-London try-out.

Scofield simply had not been ready totally to inhabit the Priest until Elsinore was behind him; he seemed diminished physically in his rumpled suit and spectacles, ineffably touching as Greene's riven anti-hero.

A changing British theatre post-Look Back in Anger made life difficult for many actors, but Scofield's career was never knocked off course. He surprised many by taking on the musical Expresso Bongo (Saville, 1958), filling an unlovely barn of a theatre with his richly enjoyable Johnnie, in this larky lampoon of Denmark Street mores.

In 1960, A Man for All Seasons (Globe, 1960 and Anta, New York, 1961) made him an international star, particularly after the screen version (1966) on which the director Fred Zinnemann battled for him against the moguls' demand for Olivier. Ruled by a flinty integrity, Sir Thomas More found the perfect interpreter in Scofield, who won an Oscar for the role; others' performances have revealed the cracks in Robert Bolt's play while with Scofield at its heart, disavowing any scruple of plaster-saint sentimentality, the man's dilemma gripped and held throughout.

Rather than pursue Hollywood offers, he chose to prepare for the biggest challenge of his collaboration with Brook. Back at Stratford, now housing the Royal Shakespeare Company, King Lear (1962) was a summation of Brook's classical work and a distillation of Scofield's formidable Shakespearean experience. It was genuinely revelatory and Scofield's courageous performance justified Peter Hall's verdict:

To me he was the first post-war actor who grasped a very modern idea and stripped his character of their glamour and sentimentality; there was a lack of crowd-pleasing; he revealed the character, warts and all.

Brook's approach was Beckettian in its evocation of a merciless world – another virtually denuded stage, of crumbling blackened wood and corroded metal – to suggest "this great stage of fools". Like the rest of a wondrous cast, Scofield went happily along with Brook's refusal to make definite moral judgements on the characters; in this godless universe Lear's arrogance was signally not underplayed, but still the character's essential humanity, increasingly powerful in the empyrean of the Dover scenes, burnt through.

His Goneril, Irene Worth, marvelled at Scofield's mesmerising ability in Lear's scene in an imaginary pulpit to mint thought with the frantic speed of a whizzing mind – "thought in an electric blender" was her description.

Peter Hall wanted to keep Scofield with the RSC. For John Schlesinger he electrified in a notoriously difficult role as Timon of Athens (Stratford, 1966). By contrast he fused the house with his comic amperage in The Government Inspector (Aldwych, 1966), and as the more outrageous ("Gawd help us all and Oscar Wilde!") of two camp coiffeurs in Charles Dyer's Staircase (Aldwych, 1966). Hall's oddly ineffectual Macbeth (Stratford, 1967) was, however, a major disappointment, with Scofield and his Lady (Vivien Merchant) ill-matched.

At the Royal Court, Scofield lit up John Osborne's Hotel in Amsterdam (1968), playing a showbiz charmer and then returned to Sloane Square for a heart-stopping Vanya in Uncle Vanya (1970). This raised comparisons with Michael Redgrave's supreme Chichester performance in its electric alternation from pathos to comedy. He returned to the Court, drawn by Christopher Hampton's new play Savages (1973), to play West, a captured diplomat.

Most of Scofield's major later performances were for the National Theatre, beginning with a glorious bang in The Captain of Köpenick (1971). He was a Pirandello admirer but the National's The Rules of the Game (at the New, 1971) was a leaden production. Yet Scofield offered a mesmerising enigma as Leone, his face a mask-like tabula rasa as he plotted his amatory revenge, suggesting a furnace below the carapace of cool.

A buoyant Volpone (1979) was driven by Scofield in ebullient form as the voracious Venetian Fox. Then came his greatest South Bank popular success – his hooded-eyed Salieri in Peter Shaffer's Amadeus (1979), the unparalleled voice scoring cadenzas of cankered jealousy and anguish in his resentment of Mozart's success.

Conserving his energy for Othello (1980) rather than star on Broadway with Amadeus, the result was a major disappointment. Peter Hall's production was stately and dull with a miscast Michael Bryant as Iago; there were flashes of essential Scofield – he played the close with Desdemona unforgettably, freighted with fathomless sorrow – but after the promise of a superb previous radio production by John Tydeman with Nicol Williamson and Scofield both in exhilarating form, this was small beer.

Back in the commercial theatre his Nat in the Broadway success I'm Not Rappaport (Apollo, 1986) had such life-enhancing zest that it (almost) papered over the piece's slickness, although not even Scofield and two of his favourite actors (Alec McCowen and Eileen Atkins) could salvage Jeffrey Archer's Exclusive (Strand, 1989). A more fitting farewell to the West End came with his magisterial Shotover in Heartbreak House (Haymarket, 1992), when he mined Shaw's comedy with spring-heeled relish.

Back at the National, his valedictory stage appearance tackled another major peak – the self-exiled caged wolf at the centre of John Gabriel Borkman (1996), with Vanessa Redgrave and Eileen Aitkins formidable, too, as warring wife and sister-in-law. He rose to magnificent heights, soaring high in the mighty final scene as Borkman surveys his dream-kingdom.

Scofield did not despise or patronise the screen although he distrusted the "celebrity" world around it (he made, in all, 16 movies). A Man for All Seasons remained his best film opportunity, but he gave other striking performances – the King of France in Kenneth Branagh's Henry V (1988), and a fittingly haunting Ghost in Franco Zefferelli's Hamlet (1990).

Unexpected choices included a delicately etched Orlik in the film of Bruce Chatwin's Utz (1991). Robert Redford's Quiz Show (1994) saw a consummate performance as Mark Van Doren, a Boston Brahmin academic whose son (Ralph Fiennes) cheats on a television show. In this study of the corruption of American values, Scofield's baffled, patrician grace made for a shining plus. Redford noticed that, despite missing home and family, on set Scofield had "a complete joy in acting".

Alongside countless radio performances – he loved the medium and recorded classics, poetry-readings, new plays and anthologies – Scofield enjoyed some diverse television work. He appeared in two of Noël Coward's last stage roles from Suite in Three Keys (1981), and also tackled some roles he had never played on stage including the Captain in Strindberg's Dance of Death (1965). He revealed himself, too, as an ideal Jamesian when playing the innocently hidebound Strether of The Ambassadors (1977).

But any survey of Scofield's quietly astonishing career must return to the stage. Without any false modesty he owned how much he genuinely enjoyed his work – for him the theatre's only big disadvantage was the necessity to work in cities – once saying:

A long time ago I realised I should have to choose between films and theatre – and the theatre has always come first. I'm not an actor because I feel the need to say "look at me – aren't I clever?" I don't have an inferiority complex I must disguise. I'm an actor because . . . oh, because I'm good at it. I can say honestly and, I hope, without self-satisfaction, that I'm happy with my lot.

That quiet certitude was the square-root of the equation which made up Scofield's theatrical mystery. It was also at the heart of the man, the world-famous star known locally in Sussex simply as "Mr Sco".

Alan Strachan

David Paul Scofield, actor: born Hurstpierpoint, West Sussex 21 January 1922; CBE 1956; married 1943 Joy Parker (one son, one daughter); died 19 March 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments