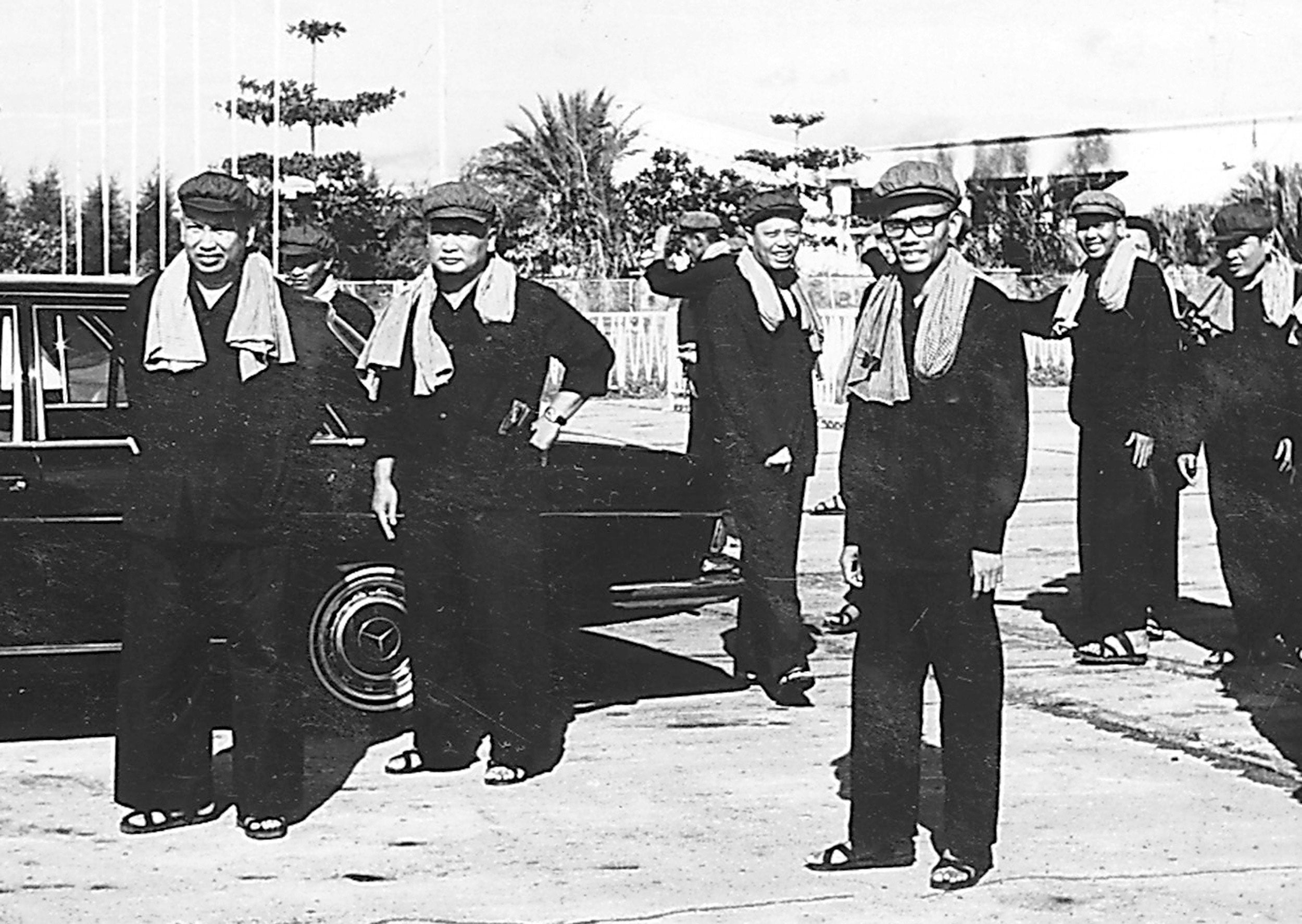

Nuon Chea: Cambodian politician and architect of the Khmer Rouge’s atrocities

As Pol Pot’s deputy he was the regime’s chief ideologue, and was convicted of crimes against humanity and genocide

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nuon Chea presided over some of the worst atrocities of Khmer Rouge rule in Cambodia in the late 1970s and ultimately was convicted of crimes against humanity and genocide.

As the secretive chief ideologue and deputy of the radical communist regime led by Pol Pot, he was the official mainly responsible for devising and operating the Khmer Rouge killing machine – carrying out a policy of mass executions that became a hallmark of Cambodia’s holocaust. It is estimated that about 2 million people died, roughly a quarter of the country’s population, from summary executions, famine, disease and overwork during the Khmer Rouge’s brief but brutal reign of terror from 1975 to 1979.

Known as “Pol Pot’s shadow” and “Brother No 2”, Nuon Chea – who has died aged 93 – was convicted of crimes against humanity by a special United Nations-backed tribunal in 2014 and sentenced to life imprisonment. After a second lengthy trial, the tribunal in 2018 also found Nuon Chea guilty of genocide against minority Cham Muslims and ethnic Vietnamese and handed him another life sentence.

According to a former Khmer Rouge security chief and prison warden, Nuon Chea personally oversaw massive purges of suspected “traitors” within Khmer Rouge ranks. Thousands were tortured into making bogus confessions at the Tuol Sleng prison in the capital, Phnom Penh, and were subsequently executed. At least 14,000 prisoners passed through the former high school’s gates. Only seven survived.

Born Lao Kim Lorn on in 1926, in Cambodia’s western Battambang province, Nuon Chea grew up in a Sino-Khmer family of modest means, the third of nine children. His father was a trader and corn farmer and his mother was a seamster. His early education was in the Thai, French and Khmer languages.

In 1942, he travelled to Bangkok in neighbouring Thailand to complete high school and pursue higher education. (Thailand took control of Battambang during the Second World War, making him a Thai citizen.) Using the pseudonym Runglert Laodi, he stayed at a temple with Buddhist monks and attended a school on the premises. Starting in 1946, he studied law at Bangkok’s Thammasat University. He also joined a leftist Thai youth group and worked as a clerk in the Thai Finance Ministry.

In 1950, Nuon Chea joined the Communist Party of Thailand while still at Thammasat. Later that year, a month after starting a clerical job at the foreign ministry, he abandoned his studies, joined the Vietnamese-led Communist Party of Indochina and returned to Cambodia to participate in the struggle against French colonialism. He adopted Nuon Chea as his “revolutionary name”.

He made his way to North Vietnam in 1953 and underwent two years of training. He then returned to Phnom Penh, where he met Pol Pot for the first time. In 1960, he was elected deputy secretary of an underground party whose members were dubbed the “Khmers Rouges” (Red Khmers) by Cambodia’s then-leader, Prince Norodom Sihanouk. It later became the Communist Party of Kampuchea, known as the shadowy “Angka”, or Organisation, and unveiled publicly only in 1977.

When Sihanouk’s government published a list of 34 suspected “subversive agents” in 1963, Pol Pot, who was on the list under his real name, fled the capital with some of his top confederates. Nuon Chea, whose identity remained secret, stayed behind, working variously as a teacher, food vendor and company clerk while trying to build the party, and occasionally travelling in disguise to visit Pol Pot in his jungle hideouts.

Eventually, after Sihanouk was deposed in a 1970 military coup, Nuon Chea fled Phnom Penh as well. An outraged Sihanouk joined forces with his former adversaries, whose ranks then swelled dramatically. By April 1975, the US-backed government’s forces were spent, and the Khmer Rouge swept into the capital.

Government troops and officials were promptly massacred. Phnom Penh and other cities were evacuated, their residents forced at gunpoint to trek into the countryside to toil in the fields. Disobedience was met with summary execution. The country was transformed into a vast slave labour camp. People, especially city dwellers, were completely expendable. It was all part of a half-baked plan – concocted in the jungles from a toxic brew of Marxism and what one scholar described as “badly digested Maoism” – to create a pure communist state in a single bound.

When it failed, resulting in famine, widespread death and economic ruin, the revolution turned on itself. Nuon Chea and other leaders blamed internal sabotage, and massive purges were launched.

Driven from power by the 1979 Vietnamese invasion, the Khmer Rouge leadership retreated to western Cambodia and resumed guerrilla warfare. But the insurgency gradually petered out in the 1990s following UN-backed elections, and Nuon Chea formally surrendered to the government in late 1998. He expected to be allowed to continue living modestly next door to Khieu Samphan, the regime’s president, in remote Pailin province, but both were arrested in 2007 on charges of crimes against humanity.

At his trial, Nuon Chea defended the decision to evacuate Cambodian cities, claiming it was to save the population from feared US bombardment and ensure access to food supplies. He blamed Vietnamese agents for virtually everything that went wrong during Khmer Rouge rule. But prosecutors presented evidence that he had personally ordered torture and executions on a massive scale.

He is survived by his wife Ly Kim Seng – who was a cook for Pol Pot, tasked with safeguarding him from poisoning – and four children.

Nuon Chea, Cambodian politician, born 7 July 1926, died 4 August 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments