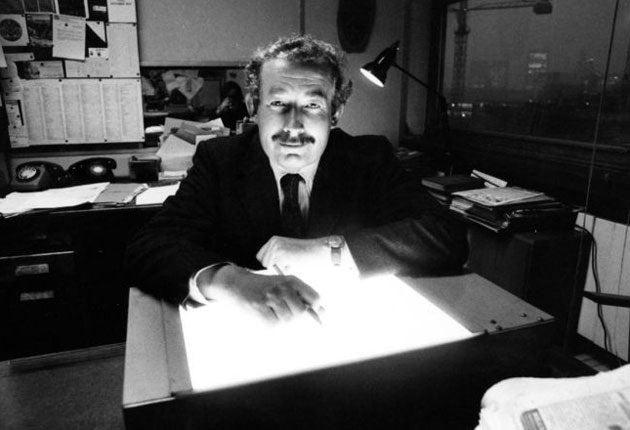

Nigel Lloyd: Tenacious production journalist who worked at 'The Independent' from its first year

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nigel Lloyd, who has died aged 79, was one of the first senior editors recruited by The Independent in 1986. A highly experienced production journalist – he was among the oldest in a young team – his role was to bring tried and tested wisdom to a project that changed the face of British journalism.

Andreas Whittam Smith, the paper’s primemover, called Lloyd “a big man”, referring not to his size, but to his personality and ability to make others sit up and take notice. Whittam Smith said: “He was in the works, below the decks, but was very experienced and got things done. Younger people looked up to him.”

The Independent was the first quality newspaper start-up in the age of new printing technology, and, although Lloyd was very much a paper-and-pencil man, he saw the necessity for a strong team of sub-editors – variously known as “super-subs” and “young Turks” – to master the new computers and produce pages on screen rather than on handwritten page plans. It was Lloyd’s lasting legacy to the new paper, and several journalists spoke last week of their debt to him.

This was a brief, but telling, marriage between old Fleet Street, personified by Lloyd, and the brave new world of paperless newsrooms and no print unions. Much of it surprised Lloyd, not least the scramble for perks among his colleagues – some of whom, to Lloyd, seemed over-fixated on the company cars they might get. He had arrived from the austere tradition of The Observer,where what mattered was belonging, as it were, to a good regiment, rather than the size of the pay packet. A colleague recalled: “He was very proper in many ways.”

Lloyd was born in 1931, the son of a north London architect, and he himself lived most of his adult life in Hampstead Garden Suburb. He went to Highgate School, from where he won an exhibition in modern history at Queen’s College, Oxford. Always curious and somewhat restless, he sensed the symbiosis between his often febrile personality and the trade of journalism.

He joined the Kemsley training scheme, and was sent to the Middlesbrough Gazette, later working on the Western Mail in Cardiff. Fleet Street was his goal, and he came to London to work on the now defunct Sunday Graphic. He found early his niche as a production journalist, and – newly married to Janice, a marketing manager – went in 1960 to Nigeria to organise the launch of the local Daily Express, founded by Roy Thomson at the moment of Nigeria’s independence.

Employment on The Observer,where he worked for 20 years, followed when David Astor, the owner/editor, was casting about for a hard-headed journalist to bring discipline to the paper’s team of talented, but often wayward writers. Lloyd had been editing Small Car, not a publication one might have expected to find at Astor’s bedside, but somehow word had reached Astor of Lloyd’s talent for getting things done – much as word would reach Whittam Smith two decades later.

Lloyd flourished on The Observer, editing its colour magazine, and eventually becoming the managing editor in charge of getting the paper onto the streets – a task that in the days of hot metal and often perverse print unions required both a firm hand and a bluff man-to-man relationship with the “inkies”. He still got Christmas cards from printers up to his death – not a claim that could be made by many journalists.

At The Observer, Lloyd developed a side line – skiing and writing about it, which started with a suggestion from Janice that a winter holiday might be a good idea. The snow slopes became an obsession, and his articles continued to appear in The Observer long after he had moved on.

Shortly before he left The Observer for The Independent, the family suffered a terrible blow, when the Lloyds’ son, Toby, died aged 19 from a brain haemorrhage. The tragedy was compounded for Lloyd as he was in Utah skiing and could not be contacted in those pre-mobile days. Alone, Janice had to take the decision – a brain scan showed a complete “wipe-out” – that no treatment should be attempted. Nigel, whose temperament was always fragile, never fully recovered from Toby’s death.

Where some found Lloyd feisty and vibrant, others saw an argumentative fellow looking for gratuitous scraps. But those who knew him well appreciated an intelligent journalist with the highest standards – second bestwas never good enough, whether Lloyd was sub-editing an article or galvanising colleagues to hit a deadline. His exasperations were short-lived; he was a man with a zest for life. He was, according to a former colleague, "One of the last great Fleet Street ‘lunchers’,” which, in Lloyd’s era, was about the highest compliment one journo could pay another.

Nigel Lloyd, journalist: born London 23July 1931; married Janice (one daughter, one son deceased); died London 11 December 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments