Nexhmije Hoxha: Wife of Albanian dictator and symbol of totalitarian repression

Her hardline opposition to reform ensured her country would endure one of the longest and bloodiest transitions after the Cold War

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

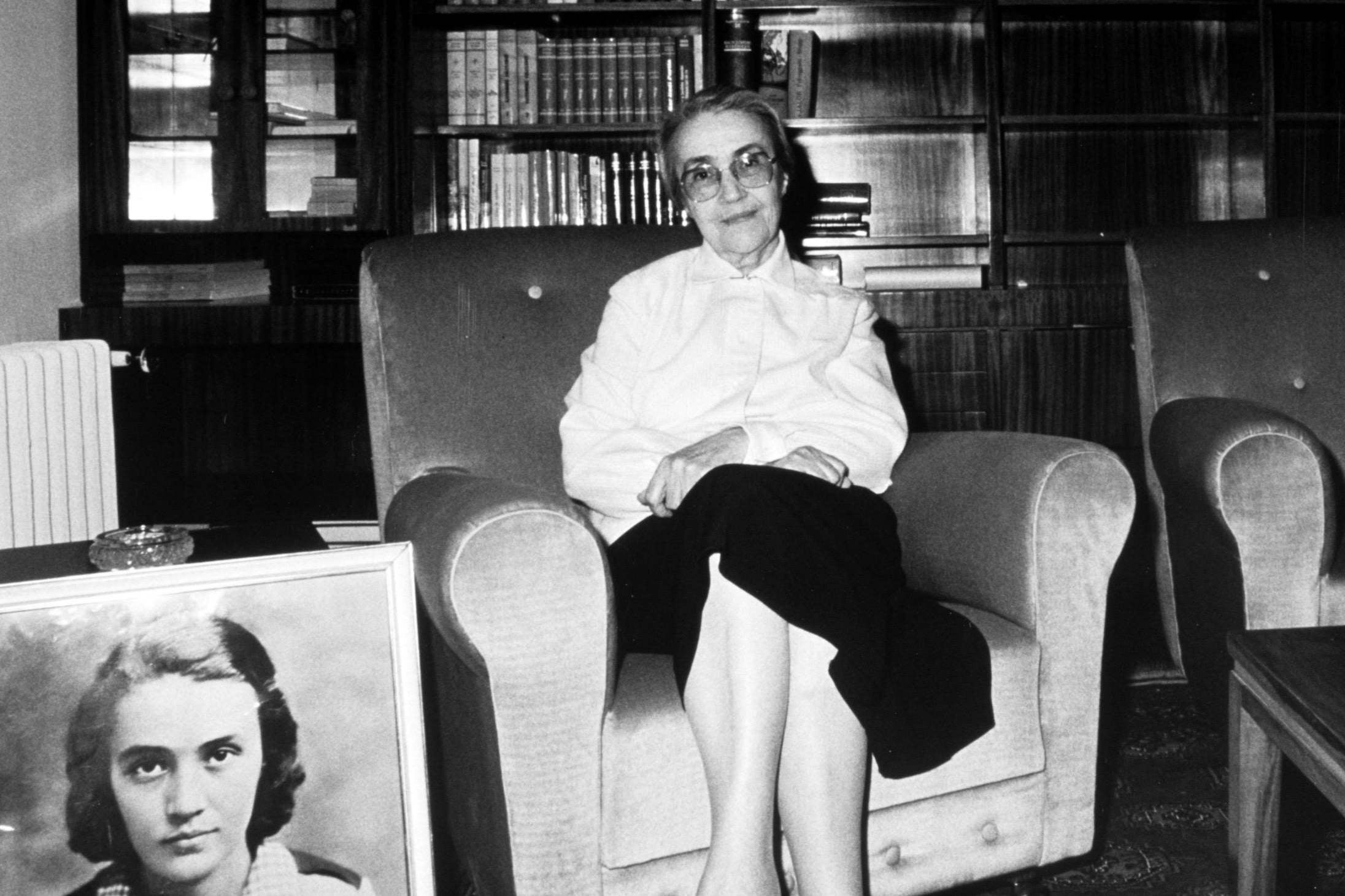

Your support makes all the difference.Like other powerful women in the traditionally male-dominated societies of the Balkans during the communist era, Nexhmije Hoxha, Albania’s “first lady” for more than 40 years, owed her influence to her husband, the country’s dictatorial ruler Enver Hoxha. But, unlike Elena Ceausescu of Romania or Mira Markovic, wife of former Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic, both of whom fell from power along with their husbands, Nexhmije Hoxha – who has died aged 99 – saw her political profile rise after her husband’s death in 1985.

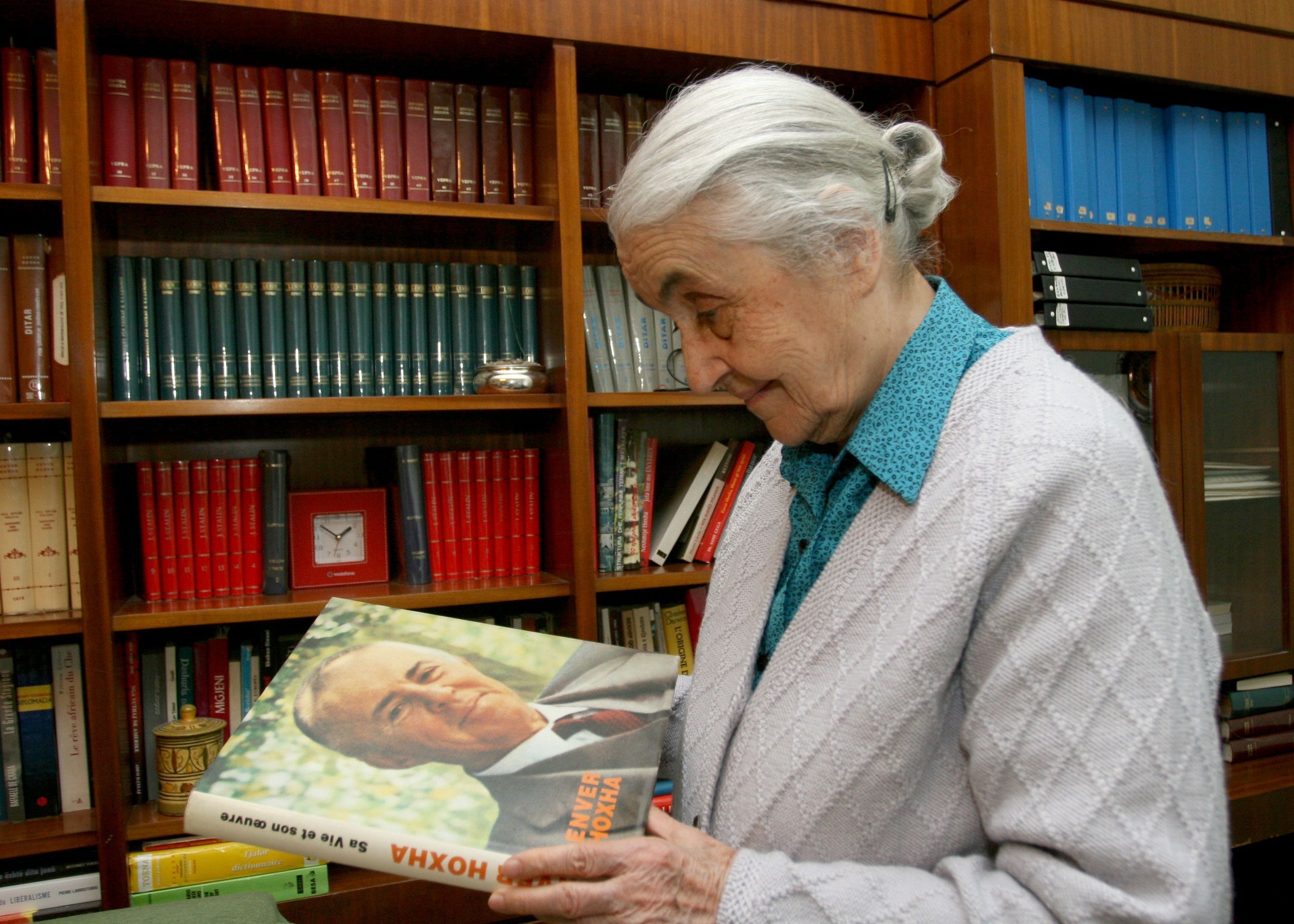

As Enver Hoxha’s widow, she became the custodian of hardline communist ideology in the second half of the 1980s. She was a leading figure in the Stalinist resistance to the hesitant and largely ineffectual reforms that her husband’s chosen successor, Ramiz Alia, tried to introduce to open up Albania to the rest of the world after a long period of self-imposed isolation.

Hoxha’s hardline policies may have contributed to prolonging, at least briefly, communist rule in Albania, which in 1991 became the last country in eastern Europe to change from one-party rule to a multi-party system. But the bitterness and frustration that had been bottled up ensured that when the collapse came, it was far more chaotic and (apart from Romania) more bloody than anywhere else in the region. Almost overnight, Albania turned from being a police state into a failed one.

In the years after the transition Hoxha was vociferous in condemning the anarchy of 1991-92, notwithstanding the fact that her faction’s policies had done much to engender the general chaos.

Nexhmije Xhuglini was born in 1921 in Monastir (later called Bitola), then part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (which became Yugoslavia), now North Macedonia. When she was eight years old, her family moved to Albania to escape economic hardship and the anti-Albanian policies of the Serb authorities. In the 1930s, while training to be a teacher, she joined the movement against King Zog’s authoritarian administration, which, in turn, was brought to an end by Mussolini’s invasion in 1939. Two years later she was among the founding members of the Albanian Communist Party, which launched a liberation war against Albania’s Italian, and later German, occupiers.

As in Yugoslavia, where the Second World War and the struggle against the fascist powers coincided with a series of civil wars, Albania’s communist partisans were also busy fighting their domestic political rivals, the royalist Legaliteti and the nationalist Balli Kombetar movements. Like Tito in Yugoslavia, whose tactics they often copied, Enver Hoxha’s troops received considerable aid from the western allies.

By the end of 1944 the communists had established control over Albania, and the following year Nexhmije married Enver Hoxha, who was to rule Albania until his death in 1985. From then, on Nexhmije Hoxha held a succession of posts in the communist-controlled youth and women’s organisations. In 1948, when the Communist Party was renamed the Albanian Workers’ Party (AWP), she became a member of the Central Committee, the party’s quasi-parliament.

Many other posts followed over the years. Hoxha became a member of a parliament whose main claim to fame was to have secured at several elections 100 per cent support for the single bloc of officially approved candidates. At the end of the 1960s she assumed the post of director of the Institute of Marxism-Leninism, the AWP’s training academy and its ideological watchdog.

Although she held more than her fair share of public posts, Hoxha never joined the AWP’s ruling politburo or had a formal job in the top administration. But her influence over her husband increased as his health declined and his paranoia over domestic and foreign enemies, real and imaginary, reached an apogee.

Nexhmije Hoxha persuaded him to anoint Ramiz Alia, another war veteran, as his successor. The new leader quickly repaid his debt to the widow when in 1986 Hoxha was promoted to the post of president of the Democratic Front, the communist-controlled umbrella group whose main functions were to supervise all social organisations and to pick the single list of candidates for Albania’s rubber-stamp parliament.

Although Alia treated her with gratitude and respect, Hoxha was to renounce him later for his weakness in presiding over the collapse of communist rule during the turmoil of 1990-92. By then Hoxha had become one of the most hated figures in Albania – a living symbol of more than four decades of totalitarian repression and an active opponent of even the mildest reforms during the swansong of the communist era.

At the end of 1991 Hoxha was arrested, and in 1993 was sentenced to 11 years’ imprisonment for abuse of power and embezzlement, relating primarily to the unauthorised use of funds to support an ostentatious lifestyle.

She was released after five years, just as Albania was sinking into its second period of anarchy with the collapse of several fraudulent get-rich-quick pyramid schemes. The subsequent uprising against President Sali Berisha’s rule and the early elections that followed returned the AWP’s reformed successor, the Socialist Party, to power in 1997.

Hoxha welcomed that victory. But to the Socialists she was a source of embarrassment whom they preferred to ignore. Thereafter, she lived in relative obscurity in a small apartment – a shrine to her late husband — on the outskirts of Tirana in a building that had previously housed the offices of a state-owned chicken farm.

Hoxha remained active into her eighties. During Nato’s bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999, she shocked her much-diminished band of Marxist-Leninist comrades in western Europe by openly supporting the west’s military action in support of her fellow-Albanians in Kosovo. She explained her stand on pragmatic grounds, comparing it with Stalin’s willingness to form an alliance with the US and Britain against Nazi Germany during the Second World War.

Her two volumes of memoirs showed no sign of willingness to acknowledge the mistakes, let alone crimes, of her husband’s repressive regime. If there was anything she regretted, it was the communists’ loss of power.

She is survived by three children.

Nexhmije Hoxha, politician, born 8 February 1921, died 26 February 2020

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments