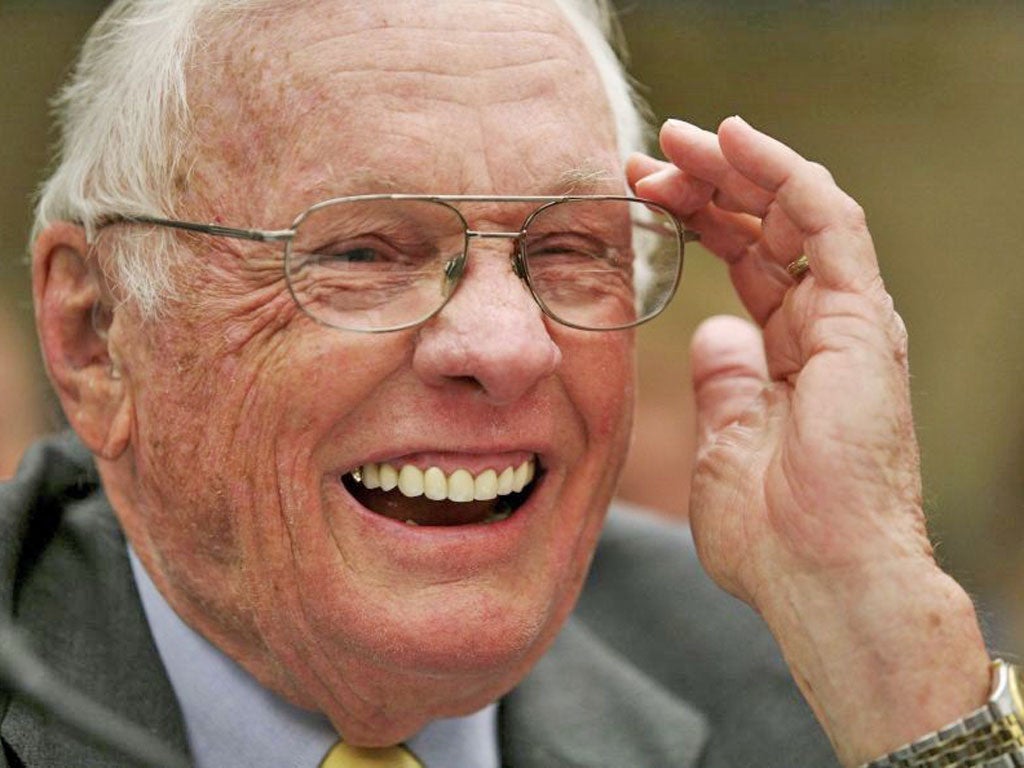

Neil Armstrong: Astronaut and scientist who became the first man on the Moon

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few people leave such a lasting imprint on human history that they are raised to the status of immortality, but, much to his distaste, Neil Armstrong was one of that select band. His televised exploits during one week in July 1969 elevated him above his fellow astronauts and test pilots to the rank of superhero, an internationally renowned figure whose name would resound throughout the ages.

The wheel of fortune decreed that Armstrong was in exactly the right place at the right time, but he had earned the right to rewrite the history books by becoming the first man to walk on the Moon. His entire life leading up this ultimate challenge had been characterised by a single-minded search for knowledge and a solitary pursuit of perfection.

Neil Alden Armstrong was born on 5 August 1930 in the living room of his grandparents' farmhouse near Wapakoneta, Ohio. He was the first of three children born to Stephen Armstrong, an Ohio state auditor, and his wife, Viola Engel. The transient nature of his father's work meant that it was hard to put down roots as the family moved six times in the first six years of Neil's life. The youngster grew up to be a self-sufficient, introverted character who would often prefer to read a book than play with other children.

One of the leading influences in moulding his character was his mother, who lavished care and attention on her offspring and spent many hours reading and talking with her eldest son.

Her efforts were rewarded with Neil's rapid educational progress. He was able to skip second grade at school because his reading had reached fifth-grade level. Later, at Wapakoneta's Blume High School, he flourished in science and mathematics, studying calculus out of school and even acting as a stand-in during the illness of his teacher.

Armstrong's obsession with flight began with a casual family outing to Cleveland municipal airport when he was two years old. Four years later, his father took him for his first plane ride and, at the age of seven, Neil built the first of hundreds of model aeroplanes. During his teens, he worked as a "grease monkey" at the local aerodrome, earning money to pay for flying lessons. He gained his pilot's licence before he was licensed to drive a car, and even built a wind tunnel in the basement of the Armstrongs' white clapboard house.

Apart from aeronautics, the young Armstrong filled his time with Boy Scout activities, playing baritone horn in the school band, learning the piano and staring through a telescope. At 17, the small, immature-looking Armstrong won a Navy scholarship and moved to Purdue University in Indiana. His academic career was interrupted two years later when he was called to active duty. After training in single-engine fighters at Pensacola because he "didn't want to be responsible for anyone else", he was sent out to the Korean War. As the youngest member of his squadron, he flew 78 combat missions from an aircraft carrier during 1950-52, and received three air medals. On one outing, after a cable stretched across a North Korean valley clipped the wing of his jet, he was able to nurse the plane back over friendly territory before bailing out.

Back at Purdue, the stronger, more mature Armstrong completed his degree in aeronautical engineering and fell in love with a dark-haired doctor's daughter named Janet Shearon. They had known each other for three years before Neil got around to asking her out on a date. "He is not one to rush into anything," she said.

Upon graduation in 1955, Armstrong joined the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics, the forerunner of Nasa. He worked at Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory, then transferred to the High Speed Flight Station at Edwards Air Force Base in California, as a civilian aeronautical test research pilot, and gained his first taste of spaceflight at the controls of the X-15 rocket plane.

On his way to the base in the Californian desert, he stopped off at a summer camp where Janet was working. "He said if I would marry him and come along in the car, he'd get six cents a mile for the trip. If I didn't, he'd only get four," she said. Unimpressed by this unromantic proposal, Janet turned him down, but she later relented and they were married in 1956. They soon moved away from the base into a relatively isolated cabin in the hills, where their first child was born in the summer of 1957.

Between 15 August 1957 and 26 July 1962, Armstrong became one of the test pilot elite, participating in four flights of the X-1B experimental aircraft and seven test flights of the X-15. He became one of the fastest humans alive, his rocket plane soaring to a speed of 6,418km/h (3,988mph) and reaching a maximum altitude of more than 63km (39 miles), beyond the Earth's atmosphere.

Some of the other pilots mistook Armstrong's shyness and isolated determination for coldness. In his book The Right Stuff, Tom Wolfe wrote that Armstrong's facial expression "hardly ever changed. You'd ask him a question, and he would just stare at you with those pale-blue eyes of his, and you'd start to ask the question again, figuring he hadn't understood, and – click – out of his mouth would come forth a sequence of long, quiet, perfectly formed, precisely thought-out sentences, full of anisotropic functions and multiple-encounter trajectories... It was as if his hesitations were just data punch-in intervals for his computer."

Armstrong excelled at the challenging, dangerous test programme, displaying steely calm in the face of disaster. Once, when he was co-piloting a B-29 bomber from which a test rocket would be launched, a propeller broke away from one engine, cut an oil line in the neighbouring engine, severed flight control cables and embedded itself into the lower fuselage. Armstrong and his companion coaxed the crippled plane back to base. On another occasion, his X-15 barely made it back to the dry lake bed at Edwards after running out of fuel.

With the transformation of the NACA into Nasa and the initiation of the manned spaceflight programme, test pilots such as Armstrong were in prime position for astronaut selection. In 1962, he became Nasa's first civilian astronaut as one of nine successful applicants from the 300 who applied to join the space agency's second astronaut group. "Space is the frontier," Armstrong told a fellow pilot. "And that's where I intend to go."

After serving on the back up crew of Gemini 5, Armstrong was given the command pilot's seat on Gemini 8. It turned out to be one of the shortest manned space missions ever flown. After launch on 16 March 1966, Armstrong and co-pilot David Scott successfully completed the first docking with another space vehicle, an Agena rocket upper stage. Within half an hour of achieving this major triumph, the crew were fighting for their lives as the Gemini-Agena combination encountered unexpected roll and yaw motion.

Uncertain of the reason for their plight, Armstrong decided to abort the mission and undock from the upper stage. As the rate of rotation increased to one revolution per second, the crew started to become disorientated and threatened with unconsciousness.

Aware that the problem must lie in the Gemini's main attitude control system, Armstrong shut it down and successfully damped down the violent spinning motion by activating the re-entry control system. Although the crew wanted to press on with the mission and Scott's planned spacewalk, ground control ordered them to return to Earth. Only 10 hours after lift-off from Florida, they made an emergency splashdown in the western Pacific and were picked up by the destroyer USS Mason.

With the completion of the Gemini programme, Armstrong began to train for a lunar landing. During manoeuvres of a training vehicle, its engine began spewing smoke and spinning erratically, 60 metres above the ground. Armstrong ejected safely seconds before the craft crashed and burned.

After two more back-up assignments on Gemini 11 and Apollo 8 – the first manned mission to leave Earth's gravitational influence and go into orbit around the Moon – Armstrong was appointed as commander of Apollo 11. He and his crew knew there was a distinct possibility that they would be first in line for a lunar landing, but all depended on the success of the preceding missions. As it turned out, Apollos 9 and 10 passed their trials with flying colours, clearing the way for Armstrong, Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin and Michael Collins to make history.

Hordes of spectators turned up at Cape Kennedy on 16 July 1969 to witness at first hand the launch of the enormous Saturn V rocket and the Apollo 11 crew. Four days later, Armstrong guided the lunar module Eagle past a large crater for a perfect touchdown on the Sea of Tranquility. "Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed," Armstrong declared.

Six and a half hours later, a worldwide TV audience of 500 million watched as Armstrong's ghostly figure slid down the ladder. His slow motion jump on to the pristine lunar surface culminated in the immortal words: "That's one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind."

As they left their footprints in the dust and learned to walk in one-sixth gravity, he and Aldrin were under instructions never to stray more than 45 metres from the lander. They had little time to stand and admire the view during their two-and-a-half-hour exploration of the Moon's surface. After setting up their experiments, collecting rock and soil samples, receiving congratulations from President Nixon and deploying the American flag, it was time to return to the Eagle for a well-earned rest before returning home.

A little over 21 hours after the historic landing, the world held its breath once again as the crew prepared to make the first lift-off from another world. Eagle's ascent stage did not let them down, and within a few hours they were reunited with Collins in the command module, Columbia. The three-day flight back home was something of an anticlimax. The crew did their best to entertain the watching millions on TV, but it was clear that they were better pilots and engineers than entertainers. One colleague called them "the quietest crew in manned spaceflight history".

After enduring a fiery re-entry to Earth's atmosphere and a splashdown in the Pacific, the trio was dressed in isolation garments and whisked to a special cabin on the aircraft carrier Hornet to begin a 17-day period of quarantine. Only then were the returning heroes released to the hugs of their families and the plaudits of the world. Armstrong was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Swamped by popular adulation and media attention, the crew were given tickertape parades in New York and Chicago, addressed a joint session of Congress and then set off for a 38-day world tour which took in 28 cities. Armstrong later made a solo Christmas visit to US troops in Vietnam.

In the years that followed, each of the astronauts coped with their new-found fame in different ways. Armstrong was determined to act as a professional ambassador for the space programme at all times while resisting all attempts to pry into his personal life.

After the excitement of Apollo 11, the most famous man in the world was given a desk job, as deputy associate administrator for aeronautics at Nasa headquarters in Washington DC.

Having fulfilled his duty to the agency, Armstrong sought sanctuary in the relative anonymity of an academic life. In 1971 he left Nasa, bought a dairy farm in Ohio, and joined the engineering faculty of the University of Cincinnati. Eventually accepted by his colleagues and students, he remained there as a professor of aerospace engineering until 1979. However, despite his attempted withdrawal from the limelight, Armstrong was unable to completely escape the attention of an adoring public. "A lot of people just wanted to touch him," said University police chief Ed Bridgeman.

Armstrong's reaction was to become even more withdrawn and reclusive. Media interviews and requests for autographs, endorsements or public appearances were largely ignored, with rare exceptions such as a 1979 TV advertisement for Chrysler cars.

He also made occasional, sometimes surprising, appearances at selected venues over the years. These included the narration of Aaron Copland's Lincoln Portrait at a Sarah Vaughan concert; conducting a Sousa march; and throwing the first ball at a baseball game in Houston.

Although Armstrong largely resisted the temptation to cash in on his fame, he was the chairman of the board of a defence electronics company, AIL Systems, and served on numerous boards of directors at different times, including United Airlines and Thiokol Corp, the manufacturer of the Space Shuttle's solid-fuel rocket boosters.

Armstrong also retained tenuous links with Nasa, turning out with his fellow crew members for Apollo 11 anniversary celebrations. He served on the National Commission on Space from 1985 to 1986, and was appointed as vice-chairman of the presidential commission that investigated the Challenger explosion in 1986. On 20 July 1989, he stood alongside George Bush as the President attempted – unavailingly – to inspire Nasa and the nation to undertake the manned exploration of Mars.

He suffered a heart attack in 1991, but recovered full fitness. He was operated on this month to relieve blocked coronary arteries, but died of complications from that surgery. In 1994 he was divorced by Janet, and shortly after married Carol Knight of Cincinnati. He leaves two children, Eric and Mark. His daughter Karen died of a brain tumour in 1959.

Neil Alden Armstrong, test pilot, astronaut and scientist: born Wapakoneta, Ohio 5 August 1930; married 1956 Janet Shearon (divorced 1994; two sons, and one daughter deceased), 1994 Carol Knight; died Cincinnati, Ohio 25 August 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments