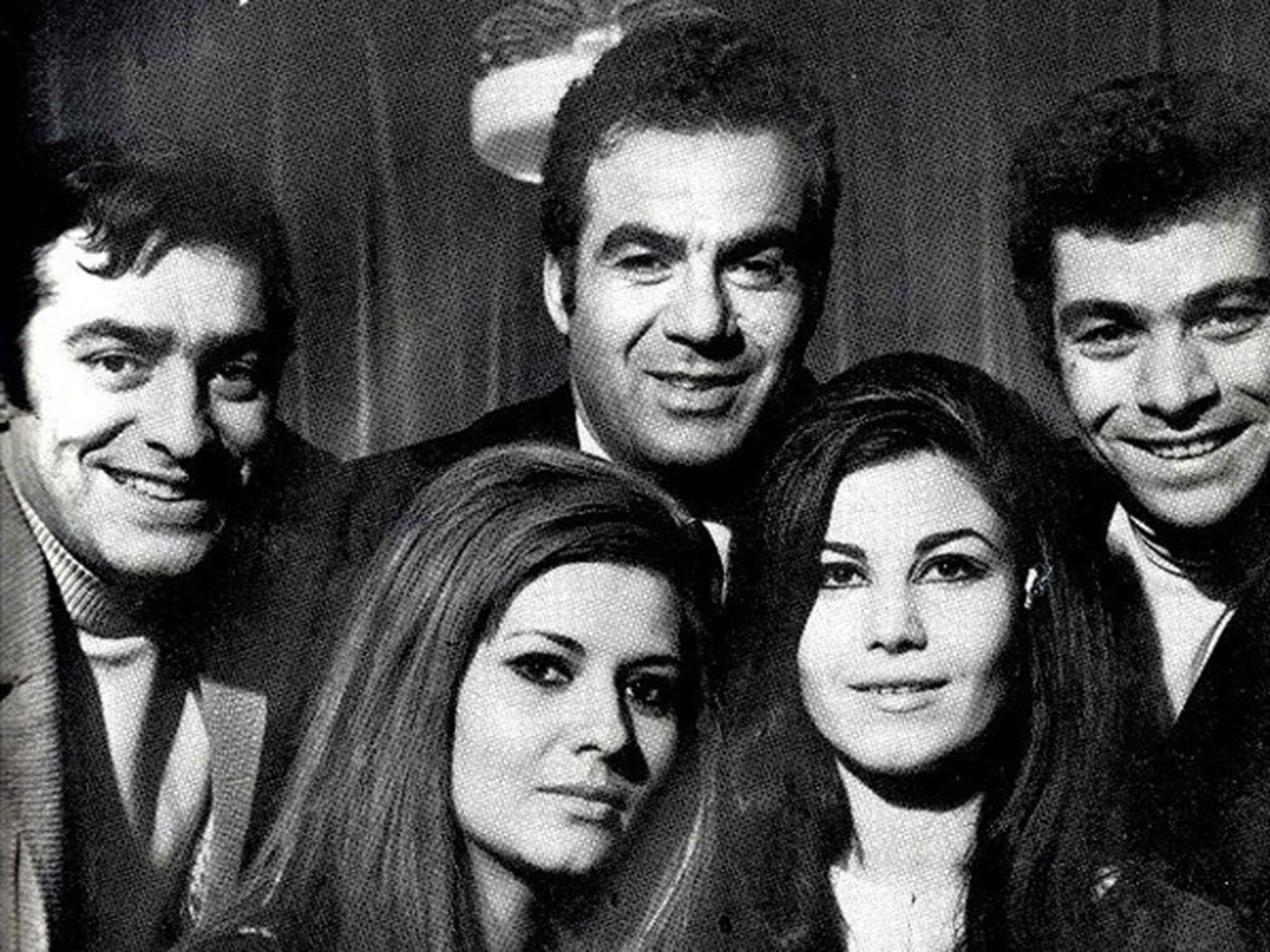

Naser Malek Motiee: Actor from Iran’s golden age of cinema whose career stopped when the Ayatollah arrived

The son of a cinema-owner, he became one of the biggest stars of the filmfarsi phenomenon

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Naser Malek Motiee was the much-loved veteran of the golden age of Iranian cinema in the 1960s and 1970s.

The actor and director, who has died aged 88, belonged to a generation of entertainment stars whose careers were cut short by the revolution of 1979. So strongly were they identified with the era of Mohammad Reza Shah, the monarch deposed by Ayatollah Khomeini, that they were unofficially banned.

Despite this imposed retirement and persona non grata status (as far as state-controlled media were concerned), Malek Motiee’s popularity was undiminished and his place in popular culture secured by contraband videos and illegal satellite dishes that proliferated in the Eighties and Nineties – while he was forced to eke out a living working in a confectionery shop before becoming an estate agent.

Thousands attended his funeral in Tehran earlier this week and vented their anger against the regime, chanting slogans such as “Our broadcaster, our shame” and “Our law enforcement, our shame”.

“Qeysar,” others shouted – Kaiser; a reference to the 1969 film of the same name and one of Malek Motiee’s most famous lines: “Help! They are killing the people!”

The authorities had anticipated the dissent, warning: “Judicial and security bodies will resolutely confront any group or individual that wants to compromise the country’s security”. Tear gas was reportedly used to disperse the crowds.

In popular memory Malek Motiee ranks with Behrooz Vossoughi and Mohammad-Ali Fardin among the three greats of filmfarsi, a genre that mixes melodrama with action, often centring around a flawed male hero.

Malek Motiee was best known for his portrayal of the jahel – Tehran’s answer to the cockney wide boy – and his witty one-liners, often improvised.

Working-class, religious but averse to making money from rackets, the jahels differed from gangsters for they strove for a sense of machismo pegged to codes of honour and a sense of justice. They were Iranian cinema’s samurai but with their trademark black suits, fedoras and a white handkerchief.

Sniffed at as laats, or louts, by the well-to-do, the screen jahel was the archetypal loveable rogue seeking redemption from past sins, turning from villain into hero in the process – Malek Motiee’s screen portrayals of the jahel are still widely regarded as unmatched.

His love of cinema began early – his father ran a cinema. In the early 1940s, in his late teens, Malek Motiei was a full-time sports instructor at a primary school in Tehran. He got a minor role, playing himself, in the 1949 film Spring Variation.

He played himself again in 1951’s The Vagabond, planting the seed of a popularity was to grow among Iranian cinemagoers across social divides.

Playing the lead in 1962’s The Velvet Hat – a reference to the “kola chapeau” donned by jahels – catapulted him to national treasure status. It was an instant classic of the genre.

While the offers rolled in, he faced a problem: he had been typecast as the wide boy with a fedora – not that that would matter in the long run.

With the arrival of “Islamic and revolutionary” values, his career was done for along with a generation of actors, pop singers and even classical singers.

In 1982 Malek Motiee did appear in The Imperilled, a prison-break thriller based on the revolution, but did not take his next role until the well-received 2014 film Negar’s Role.

In a rare newspaper interview, Malek Motiee said the hardship that endured was “indescribable” and that he found being forced into seclusion in what were long wilderness years “heartbreaking”.

Addressing mourners at his funeral crowd, Malek Motiee’s son, Amir Ali – who survives him with daughter sister, Shirin and wife Mahin – noted that the media, which had ignored him during his lifetime, had in effect lifted the ban. He said: “Why are my father’s photos shown on news channels now? Why are photos of an actor only allowed after his death?”

Naser Malek Motiee, Iranian actor, born 29 March 1930, died 25 May 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments