Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian: Artist who mixed geometrics with patterning of her Iranian heritage

Her beguiling works combined traditional Iranian mosaics with the abstract

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

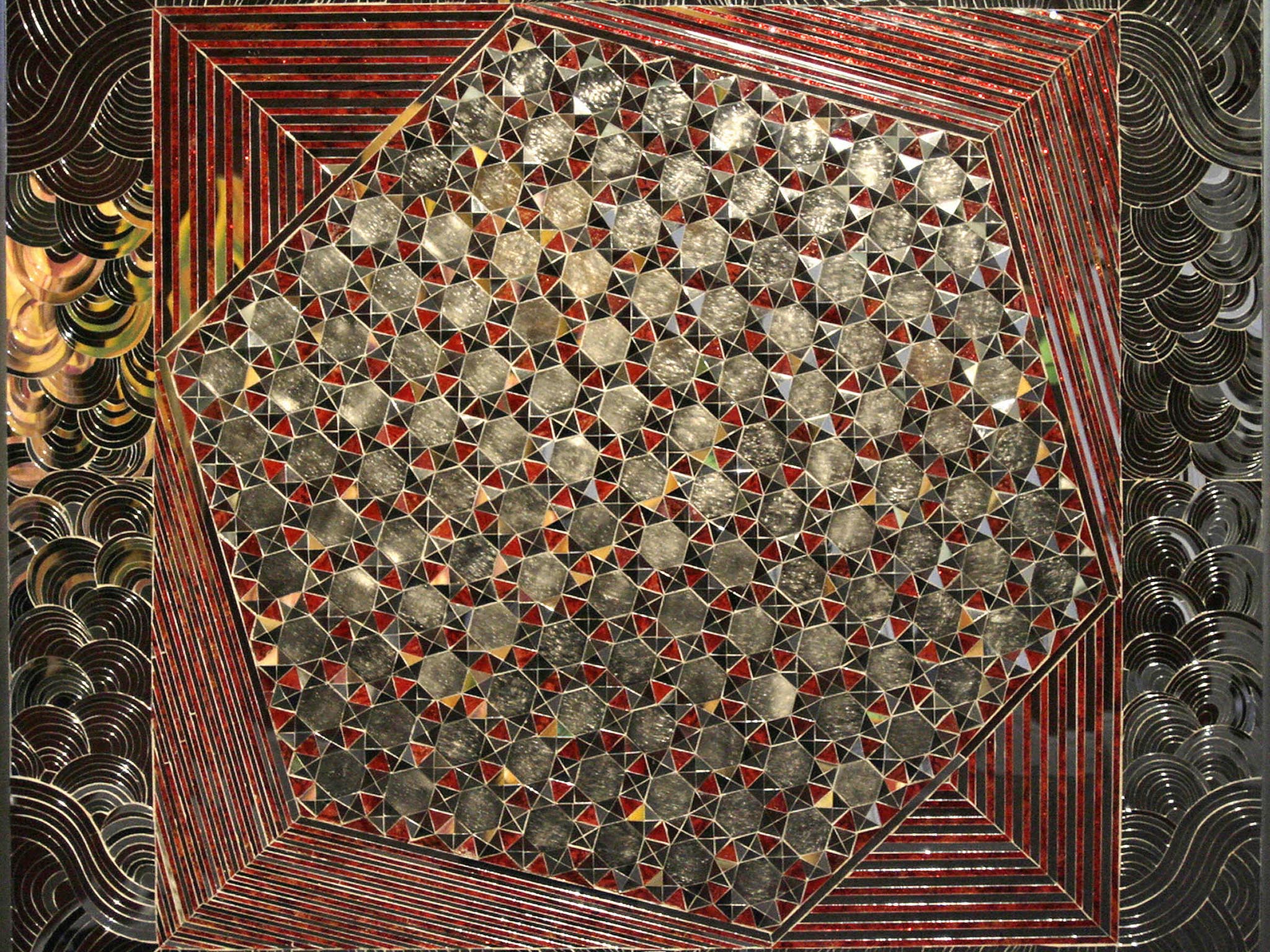

Your support makes all the difference.Best known for mirror mosaic and reverse-painted glass, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian’s work mixes geometric abstraction with the cosmic patterning of her Iranian heritage. In an interview with curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist in 2015, Farmanfarmaian said that she had discovered that “geometry has meaning from the start. It goes from triangle to square to pentagon, hexagon, all the way up to 12, which is the zodiac – the 12 months of the year.”

Farmanfarmaian lived life in successive exiles between Tehran and New York – in the 1950s, she was a member of the latter’s renowned burgeoning avant-garde art scene, befriending the likes of Andy Warhol, Frank Stella and Milton Avery. She then went on to become one of Iran’s most prominent artists of the contemporary period.

The marriage of the local and the global that reverberates in Farmanfarmaian’s work evokes French-Caribbean philosopher Édouard Glissant’s concept of mondialité. Glissant stresses the importance of preventing the erasure of indigenous cultures by resisting the homogenising forces of globalisation, and instead using global dialogue for progress and growth.

Born Monir Shahroudy in 1924 in the city of Qazvin, an ancient capital during the Persian Empire now known as the calligraphy capital of Iran, she spent her early childhood living in a resplendent house that had been decorated with wall paintings of Islamic designs during the Safavid period.

Farmanfarmaian later moved to Tehran after her father was appointed a position in the parliament. She attended the Fine Arts College of Tehran University, where she met Manoucher Yektai, who would later become her first husband.

During the Second World War, the couple moved to New York where Farmanfarmaian began to associate with the era’s most influential artists, such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning.

Her and Yektai got married in 1950. He was also an artist, and in playing the role of the supportive wife of a man who aspires to be an acclaimed painter, Farmanfarmaian was forced to sublimate her own dreams and promote his career above her own. Together they had one child, Nima, but in 1953, they divorced.

Farmanfarmaian worked as a freelance fashion illustrator for magazines and agents to support herself and Nima following her divorce. She then acquired a full-time job at the department store Bonwit Teller, which was where she met Warhol, who was also working there. “Later, in the late 1970s, I teased him about how important he had become with the soup cans and so on. I asked him, ‘Do you remember, you used to draw shoes for $25 (£20) each, for Bonwit Teller?’”

Farmanfarmaian made the decision to return to Iran in 1957. Iran had always inspired her creatively, as she explained to The Guardian in 2017: “It has always been my first love.” And furthermore, as she told Hans-Ulrich Obrist, “a wonderful gentleman by the name of Abol-Bashar Farmanfarmaian asked me to marry him … he was the only one who ever believed that I was really an artist. My friends, my family, my artist friends never told me I had any talent; I still don’t believe that I do, but they certainly didn’t believe it.”

Back in Iran, Farmanfarmaian set up her own studio for the first time. Inspired by the resident culture, she discovered “a fascination with tribal and folk artistic tradition”, and she worked closely with local craftsmen in their centuries-old techniques. Her work was greatly influenced by mirror-work and the mosaics of the country’s religious shrines. In 1966, she visited the high domed ceilings of the 14th Shrine of Shah Cheragh, the King of Light. She recalled, “It was like a living theatre; people came in all their different outfits and wailed and begged to the shrine, and all the crying was reflected all over the ceiling and everywhere and I cried too because all of the beautiful reflections. I said to myself, I must make something like that, something that people can have in their homes.”

She was also influenced by Sufi teachings on the origin and evolution of the universe. “I read up on Sufi cosmology and the arcane symbolism of shapes,” Farmanfarmaian wrote in her book A Mirror Garden, “how the universe is expressed through points and lines and angles, how form is born of numbers and the elements lock in the hexagon”.

Furthermore, she undertook extensive local research to supplement and enrich what she had learned from her prolific friends and the art scene in New York. “Now and then I would say to my husband, ‘I’m heading out to the desert.’ We had a Volvo, and I would take the sleeping bag and some food boxes and travel all over Iran. I went to old cities and ruins. I discovered the tribal peoples, the Qashqai, the Turkomen, the Lurs, the Yamuts and the Kurds – they were wonderful people. I used to sleep in their tents or in the cafe by the side of the road.”

Farmanfarmaian worked tirelessly to preserve pieces of local cultures of historic significance that were disappearing, like the jewellery of the minority Turkic ethnic group living in northern and northeastern Iran whose leaders had ruled much of Persia (modern-day Iran) before they were overthrown by the Safavid dynasty in 1501. She began collecting their handicrafts after discovering an antique shopkeeper was buying it up only for its value as melted down silver.

She also collected paintings of primitive scenes that used to be employed in storytelling performance. She travelled around in search of these pieces to procure and entered the local coffeehouses in which they were often displayed – despite custom dictating that these were the domain of a male-only clientele.

During this long period back home in which she was happily married, Farmanfarmaian flourished as an artist. She represented Iran at the 1958 Venice Biennale – winning a gold medal – as well as showing in the first Tehran Biennial in the same year.

The year 1979 marks Iran’s Islamic Revolution in which the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was overthrown and supplanted by the rule of the religious clergy led by their spiritual leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

This occurred while Farmanfarmaian and her husband were away in New York visiting family, and they found themselves exiled from Iran. With the Islamic Revolution came a wave of crackdowns and censorship. Artists remaining in the country were forced to contend with the ever-changing currents of what was deemed acceptable and not. All of Farmanfarmaian’s collected works were confiscated by the new regime. “The best antiques and carpets found their way into the mullahs’ homes,” Farmanfarmaian lamented in her book. Furthermore, Abol-Bashar Farmanfarmaian descended from an old Iranian family that was influential before the revolution, so the couple opted to remain in exile for many years.

The lack of materials and comparatively inexperienced workers in America restricted Farmanfarmaian’s mirror mosaic work, so she instead focused more on commissions, textile designs and drawing.

Eventually, Farmanfarmaian’s work began to gain larger audiences, but she faced many obstacles. “In America, after the revolution, after the [Gulf] war, nobody wanted to do anything with Iran,” she told The Guardian in 2011. “None of the galleries wanted to talk to me. And after September 11 – my God. No way.”

Farmanfarmaian permanently moved back to Iran in 2004, where her work had a receptive audience, despite her having been often critical of the country and the direction it had taken since the Islamic Revolution. One of her works, “Lightning for Neda”, was created in tribute to Neda Agha-Soltan, a young Iranian woman shot dead in front of cameras during the 2009 presidential election protests.

In 2017, the Monir Museum opened in Tehran. It was the first Iranian museum dedicated to the works of a female artist. Farmanfarmaian personally donated more than 50 works spanning six decades of her career to the museum. These include the Heartache series, which consists of boxes with collages of photos, prints and objects that celebrate Farmanfarmaian’s life with her beloved husband, who died of leukaemia in 1991. The museum is interestingly named only after Farmanfarmaian’s first name, which is perhaps a subtle derogation of her husband’s family name Farmanfarmaian, with its evocations of the old regime.

Farmanfarmaian died in April in Tehran at the age of 96. She is survived by her daughters Nima Isham and Zahra Farmanfarmaian; five grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, artist, born 16 December 1922, died 20 April 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments