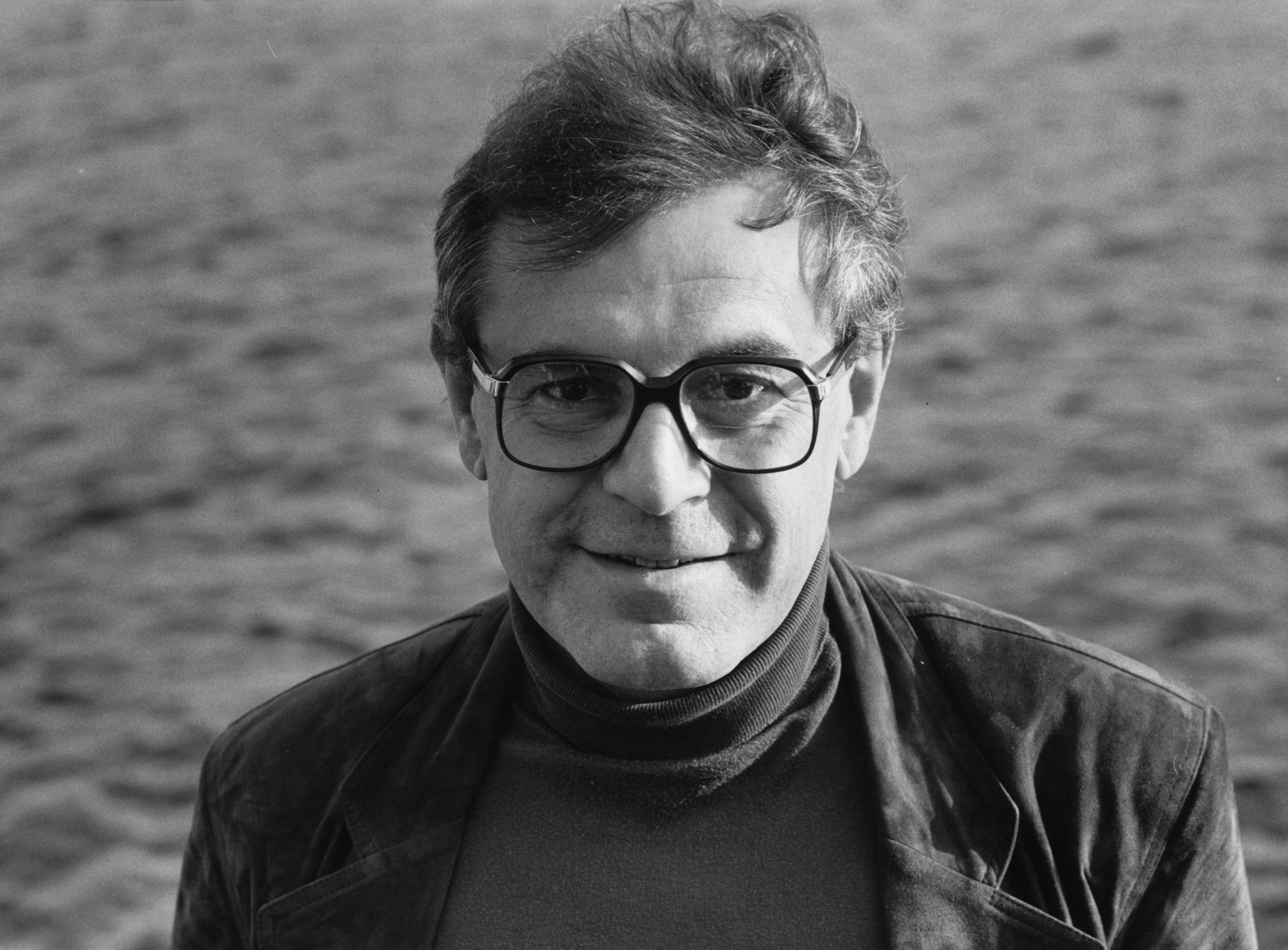

Milos Forman: Czech-born filmmaker who won Oscars for ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ and ‘Amadeus’

A late '60s exile from the repressive regime in his native Czechoslovakia, the director made a string of spirited, rebellious films in the US

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Milos Forman was the Czech-born filmmaker who left his homeland for the US in the 1960s – there, in exile, he became a two-time Oscar-winner as the director of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) and Amadeus (1984).

Forman, who has died aged 86, made several acclaimed films in the 1960s in his native Czechoslovakia before settling in the United States after the 1968 Soviet invasion ended the brief period of cultural flowering known as Prague Spring.

Over the next four decades, he made fewer than 10 films, each vastly different from the others. But throughout most of Forman’s films – including 1996’s The People vs. Larry Flynt and 2006’s Goya’s Ghosts – there was an abiding spirit of the rebel seeking to be free.

“I lived in a society where people who called for censorship won,” Forman, who grew up under Communism and lost both parents in the Holocaust, said in 1996. “I know what a devastating effect it has on life – not only on the artist but on everybody.”

He was struggling to make a living, with only one US film to his credit – 1971’s Taking Off, a box-office flop in spite of its name – when he was chosen by producers Saul Zaentz and Michael Douglas to direct One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

It was based on the novel by Ken Kesey, a touchstone of the Sixties counterculture in America, about a rebellious gadfly’s efforts to survive inside a prison-like asylum. The film was shot at the state psychiatric hospital in Oregon, with Jack Nicholson in the lead role as Randle P McMurphy.

Several celebrated actresses, including Anne Bancroft, Ellen Burstyn, Colleen Dewhurst and Angela Lansbury, turned down the part of Nurse Ratched, a martinet who tried to keep the men in her ward sedated and under control.

Forman then cast Louise Fletcher, a little-known actress who hadn’t worked in years, as Nurse Ratched, who was the film’s principal female character.

When the film was released in 1975, it was a critical and popular success and was viewed as a biting indictment of the authoritarian impulse to stifle individuality. Cuckoo’s Nest won five Academy Awards, including best picture. Forman won the Oscar for directing, and Nicholson and Fletcher won for best actor and best actress, respectively.

Forman’s next two films – a 1979 version of Hair, the long-running Broadway musical, and Ragtime based on EL Doctorow’s novel – received lukewarm reviews.

With his next effort, Amadeus, he ventured into the world of 18th-century classical music, reshaping Peter Shaffer’s play as a psychological exploration of genius and jealousy. The genius was the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, depicted in the film as childish and ill-mannered whenever engaged in anything not related to music. The jealousy comes from his less-talented rival, Antonio Salieri, who goes so far as to plot Mozart’s murder.

“It’s not a petty jealousy,” Forman said in 1984. “It’s a grand jealousy.”

With sumptuous costumes and the soaring strains of Mozart’s music, Amadeus was a tour-de-force, not the least because it was filmed in Prague, where Forman had studied and worked in his youth.

Prague was one of the few cities in Europe that still had cobblestone streets and 18th-century buildings – including the opera house where Mozart had premiered Don Giovanni.

Forman drew remarkable performances from the two central characters, played by two relatively unknown actors, Tom Hulce as Mozart and F Murray Abraham as Salieri, whose villainy grows more tortured and complex throughout. Both actors were nominated for best-actor Oscars.

“It’s a wonderful story,” Forman said, “and I think there’s a little bit of Mozart in all of us – and quite a bit of Salieri in all of us.”

Amadeus swept the 1985 Academy Awards, taking eight Oscars in all, including best picture, best actor for F Murray Abraham and Forman’s second award as best director.

He had been allowed to return to Czechoslovakia – still under Communist control at the time – only if he didn’t seek out his old friends among the dissidents. But the symbolic importance of the native’s triumphant return could not be escaped. Even members of Czech security forces got jobs as extras in Amadeus.

“The people considered it a victory for me,” Forman said in 2002, “that the authorities had to bow to the almighty dollar and let the traitor back.”

Jan Tomas Forman was born in Caslav, Czechoslovakia. His father was a teacher, his mother a homemaker.

His father was jailed during the Second World War for distributing subversive literature, and his mother was seized soon afterward. Both parents were nominally Christian but died in Nazi concentration camps. Years later, Forman learned that his mother confessed to a fellow inmate that his natural father had been a Jewish architect.

Forman lived in the homes of relatives before enrolling in the film programme of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague, from which he graduated in 1954. One of his teachers was Milan Kundera.

He worked for Czech television and for a film studio before completing his first feature-length film, Black Peter, in 1963. His next film, 1964’s Loves of a Blonde, received acclaim at international film festivals.

Forman’s next film, The Firemen’s Ball (1967), included a scene of a house burning down while the firefighters are celebrating at a retirement party. The film was banned in Czechoslovakia, and Forman was forced to apologise to the country’s firefighters.

His marriages to Jana Brejchova – the lead actress in Loves of a Blonde – and Vera Kresadlova ended in divorce.

Survivors include his wife of 18 years, Martina Zborilova of Warren, Connecticut; twin sons from his second marriage; and twin sons from his third marriage.

After Forman published an autobiography in 1994, he continued directing films, most notably The People vs Larry Flynt, a raucous and bawdy account of the First Amendment battles of Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt, played by Woody Harrelson. He received his third Oscar nomination for best director.

In 1999, he directed Man on the Moon, starring Jim Carrey, about life of comedian Andy Kaufman. Forman’s final film, Goya’s Ghosts (2006), was about the Spanish artist.

Forman said that he had stage fright and could never have worked as an actor, but he had a few cameo roles in films, including Nora Ephron’s Heartburn in 1986.

“Every director should try it, just to know how it feels,” he said in 2007. “Get in front of the camera, and you see it’s not at all so easy.”

Milos Forman, filmmaker, born 18 February 1932, died 13 April 2018

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments