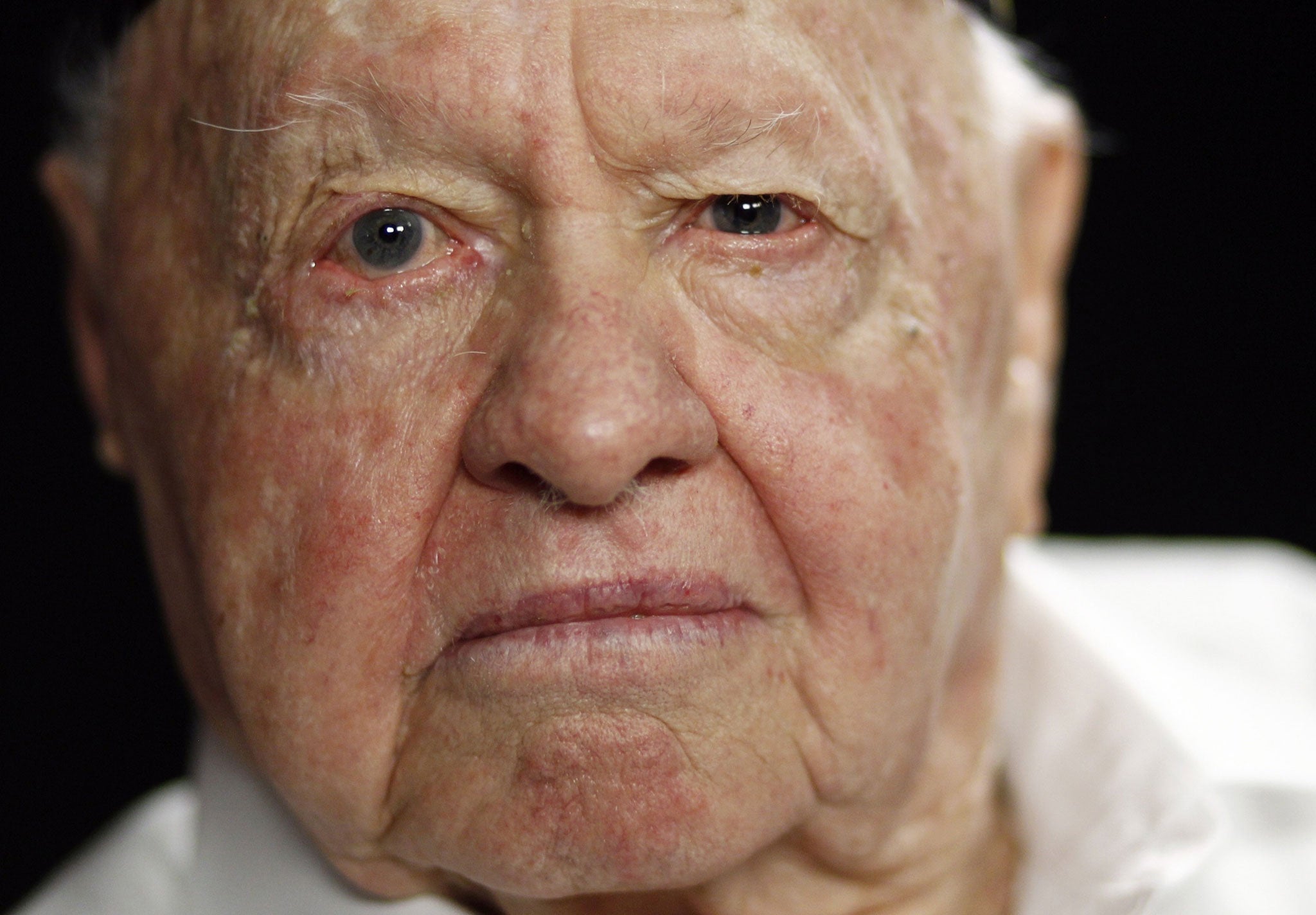

Mickey Rooney: Diminutive Hollywood dynamo best known for his role as the all-American teen Andy Hardy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.During Hollywood’s golden years of the late Thirties and early Forties, pint-sized Mickey Rooney was the most popular star on the screen. He was a dynamo who could sing, dance, play the drums and piano, clown or move viewers to tears.

His boundless energy, total commitment and talent for performing endeared him to audiences – whether he was playing the all-American youth in the popular Andy Hardy series, a stage-struck youngster putting on a show in a barn with Judy Garland in a string of bright musicals, or a wayward lad being reformed by a kindly priest in Boys Town. He was also a memorable Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and gave a moving performance in The Human Comedy, which earned him one of his four Oscar nominations. But by the end of the Forties his career slumped badly, and thereafter it fluctuated wildly, matched by a quixotic and extravagant lifestyle. His eight marriages (including one to Ava Gardner) made headlines, as did reports of his drinking and the fortune he lost through bad investments, alimony payments and gambling. After announcing his retirement in 1978, he made his Broadway debut the following year and had a tremendous personal triumph, starring with Ann Miller in the revue Sugar Babies.

Rooney was born Ninian Joseph Yule Jnr in a theatrical boarding house in Brooklyn, New York, on 23 September 1920. His parents, Joe and Nellie Yule, were vaudeville performers, and when Mickey was only 15 months old he was playing drums in their act. Soon he was also singing, dancing, acting in comedy sketches and displaying a flair for mimicry. When he was four years old, his parents separated and his mother later took him to Hollywood, where he made his screen debut playing a midget in the short Not to Be Trusted (1926). After playing another midget in Orchids and Ermine (1927), starring Colleen Moore, he auditioned for a screen series based on the Toonerville Folks newspaper comic strip by Fontaine Fox. He won the leading role of Mickey McGuire in the series and, with his hair dyed dark to match the cartoon original, played in over 50 short subjects from 1927 to 1932.

Though the producers had him legally adopt the name Mickey McGuire (so that they would not have to pay royalties to Fox), it was so associated with the series that when Universal hired him to act in Information Kid (1932) he became Mickey Rooney. Soon in demand for feature films, he acted in a Tom Mix western, My Pal the King (1932), Charles Brabin’s tough tale of the fight against big-city gangsters, Beast of the City (1932), and played Clark Gable as a child in Manhattan Melodrama (1934). Signed to a contract by MGM, he was loaned to Warners to play Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), a role he had played with great success on stage at the Hollywood Bowl in 1933, under the direction of Max Reinhardt, who co-directed the film with William Dieterle.

Two-thirds of the film had been shot when Rooney, defying studio instructions, went tobogganing and broke his leg in a crash. Ten days later he was well enough to come back to the set with the leg in a cast, and all subsequent shots of his were taken from the waist up. MGM were impressed enough to give Rooney a new contract. He had excellent roles in Ah, Wilderness! (1935) and three films starring Freddie Bartholomew: Little Lord Fauntleroy (1936), The Devil Is a Sissy (1936) and Captains Courageous (1937).

Then came the film that altered the course of his career. Producer Sam Marx had bought the rights to a wholesome family play, Skidding, and suggested to the studio that it would make a nice B picture. Frankie Thomas was set to play the juvenile of the family, Andy Hardy, but by the time production was ready to start he had grown too tall, and Rooney took the part. To the studio’s surprise, A Family Affair – though ignored or disdained by critics – became a tremendous success with audiences and had exhibitors asking for a sequel. The series promoted all of the family values held dear by the studio head, Louis B. Mayer, with a highlight of each film the man-to-man talk between father (originally Lionel Barrymore, then Lewis Stone) and son, usually after Andy had found himself in some sort of predicament.

The Andy Hardy films (15 in all) were to make a fortune for the studio, and also provided a training ground for newcomers being groomed for stardom. Lana Turner, Esther Williams, Donna Reed and Kathryn Grayson were among those who played Andy’s girlfriends, and Judy Garland was a semi-regular as neighbour Betsy Booth.

Lana Turner had been a date of Rooney’s before she was hired by MGM, and according to the actor, he later discovered that she had aborted their baby. “She and her mother probably knew, deep down, that a child made no sense at all for either of us, then,” he said. “We were both children ourselves.”

Rooney’s great success as Andy Hardy was consolidated by his performance in Boys Town (1938). Spencer Tracy won an Oscar for his portrayal of the real-life Father Flanagan, who founded a home for wayward boys, but many felt the film was stolen by Rooney as the tough youth who is finally won over. At that year’s Oscars ceremony, Rooney and singing star Deanna Durbin were both awarded special miniature Oscars for their “significant contribution in bringing to the screen the spirit and personification of youth.” At the end of 1938, Rooney was cited as the top box-office star of the year, and in 1939 he was nominated for an Oscar as Best Actor for his performance in Babes in Arms. His competition: Laurence Olivier, Clark Gable, James Stewart and Robert Donat (who won, for Goodbye Mr Chips).

Rooney had first teamed up with Judy Garland in a racing story, Thoroughbreds Don’t Cry (1937), but Babes in Arms was their first major co-starring vehicle. Directed by Busby Berkeley, it was a fine showcase for both stars, with Rooney singing, dancing, playing seven musical instruments and displaying his skill for mimicry with hilarious impersonations of Lionel Barrymore and Clark Gable. He and Garland introduced the song “Good Morning” in the film and were to be teamed as stars of three other big musicals. Strike Up the Band (1940) had a number showcasing Rooney’s drumming skills, and was a tour de force for the actor; Babes on Broadway (1941) was full of choice moments, including Rooney’s priceless impersonation of Carmen Miranda; and Girl Crazy (1943) had the advantage of several Gershwin numbers written for the original stage show, climaxing with a spectacular “I Got Rhythm”.

Between these films, Rooney had also starred in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1939), Young Tom Edison (1940) and A Yank at Eton (1942).

In 1943 Rooney gave one of his finest performances in a screen transcription of William Saroyan’s novel The Human Comedy, playing a boy growing up in a small town during the war. As a Western Union delivery boy, he has to deliver telegrams which often bear tragic news, and in a poignant scene has to read a telegram announcing his brother’s death. Dorothy Morris, who co-starred in the film, later said that, “Mickey was fabulous, bursting with talent and energy. The Human Comedy was the first really serious thing I ever saw him do. It was Mickey who really directed it – at least the family scenes in which we appear. Mickey worked with us all, bringing out the best we had... He put his heart and soul into that picture because MGM was giving him a chance, at last, to be someone other than Andy Hardy.” Director Clarence Brown simply said, “Mickey Rooney, to me, is the closest thing to a genius I ever worked with. I still don’t know how he did it. Between takes he’d be off somewhere calling his bookmaker – then he’d come back and go straight into a scene as if he’d been working on it for three days.” For his performance, he received his second Oscar nomination.

Rooney left MGM to join the Army, and when he returned to Hollywood neither the studio nor his career was ever quite the same. He made Love Laughs at Andy Hardy (1946), but the response prompted the studio to call a halt to the series. He made Rouben Mamoulian’s Summer Holiday, a musical version of Ah, Wilderness! (in which he now played the older brother), which was received so badly at previews that the studio did not release it until 1948, two years after it was made.

Rooney was given the key role of Lorenz Hart in Words and Music (1948), a tribute to songwriters Rodgers and Hart which paid little attention to accuracy. Since his character’s homosexuality could not be even hinted at, Hart seems incredibly lachrymose and self-pitying when all he has to contend with is being short. Rooney took a lot of the criticism that should have been levelled at the script, though his version of “Manhattan” became a popular recording.

The film also marked the last screen teaming of Rooney and Garland. Rooney always described his relationship with Garland as like that of brother and sister, and he was consistently gallant and admiring when asked about her.

After Words and Music, Rooney left MGM, later admitting that he was swell-headed at the time, and did not expect freelancing to be so difficult. He formed his own production company, which went broke after a few movies, though one of them, Quicksand (1950), is a powerfully atmospheric film noir. He also made a disastrous trip to England to star at the London Palladium at the beginning of the “American invasion” of the theatre in the post-war years. His ebullient self-confidence on his arrival and egocentric statements to the press alienated the public, and his act was greeted with hostility and bad reviews.

In order to get good screen roles, he had to take second billing to Bob Hope in Off Limits (1953), William Holden in The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1954) and Wendell Corey in the war film The Bold and the Brave (1956), for which he won an Oscar nomination as Best Supporting Actor for his role as a private who wins $30,000 in a crap game, then is killed during a patrol while trying to guard the cash. Plump and balding, he began to establish his reputation as a reliable character actor, and in 1957 was nominated for an Emmy for his role as a monstrous comic in Rod Serling’s television play The Comedian.

In 1958 he returned to MGM for an ill-advised sequel, Andy Hardy Comes Home, but he had a good role as “Killer” Mears in a remake of the John Wexley play about prison life, The Last Mile (1959). His friend Richard Quine gave him the guest role of a querulous Japanese man infuriated by his neighbour Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), but allowed the actor to go way over the top (“I was downright ashamed of my role”); but the following year he gave a beautifully modulated performance as the trainer of a faded boxer in Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962). The year of the film’s release he filed for bankruptcy, claiming he had nothing left of the $12m he had earned during his career. A combination of bad get-rich-quick investments, gambling and alimony had accounted for much of it.

Rooney was married eight times. His first wife was Ava Gardner, who married him in 1941 when she was 19 and Rooney 21, and the actor later blamed the union’s failure on himself. “I thought that marriage was a small dictatorship in which the husband is the dictator and the wife the underling... What an impossible son of a bitch I must have been.” His third wife, in 1949, was the actress Martha Vickers, best remembered for her role as a nymphomaniac in The Big Sleep. They had one son, and were divorced in 1951. He married his fifth wife, Barbara Ann Thomason in 1959, and they had four children during their first four years of marriage. But in 1965 Rooney discovered that she was having an affair with Alain Delon’s handsome former stunt double, Milos Milosevic. Rooney filed for divorce, but his wife, fearful that she would lose custody of their children, agreed not to see Milosevic again and there was a reconciliation while Rooney was in hospital with a virus infection contracted in the Philippines while filming Ambush Bay. On 1 February 1966, Rooney’s wife visited him in hospital, then returned to their Brentwood home escorted by Milosevic. Thomason’s best friend, Marge Lane, later stated that she had been told by Rooney’s wife, “I want Milos to leave, but he won’t go.” The following day, the bodies of Thomason and Milosevic were found in the master bedroom, Milosevic having apparently shot Barbara and then himself.

Nine months later Rooney married Marge Lane, but it was a short union. “I couldn’t understand,” wrote Rooney, “why Marge Lane was asking for half of my estate when we’d only been married 100 days. The judge agreed with me and sent my sixth wife packing with small change.” His eighth and final wife was blonde country-and-western singer Jan Chamberlin.

Through all his travails, Rooney continued to seek work, his energy unabated. He was part of the all-star cast in Stanley Kramer’s overblown comedy It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), performed a night club act, appeared in summer stock versions of Broadway shows such as A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, and made diverse television appearances.

He had a good role as a grizzled lighthouse keeper in the Disney feature Pete’s Dragon (1977) and won his fourth Oscar nomination in 1979 for playing a former jockey in The Black Stallion (1979). He was acclaimed for his star turn in the television movie Bill (1981), his perceptive portrayal of an adult with learning difficulties winning him the Emmy and the Golden Globe Award as Best Actor. In 2006, he appeared alongside Dick Van Dyke in the Ben Stiller comedy Night at the Museum – and in 2011, he had a cameo in The Muppets.

He had filmed his part in Bill by day while at night appearing on Broadway in Sugar Babies, a joyous celebration of burlesque which had opened in 1979 to critical raves. Co-starring Ann Miller in a collection of nostalgic songs, dances and vaudeville sketches, it was tailor-made for Rooney, who found himself the object of the sort of adulation he had not received for over 30 years.

When in 1983 he was given a special Oscar for Lifelong Career Achievement, presenter Bob Hope called him, “The kid who illuminated all our yesterdays, and the man who brightens all our todays.”

Mickey Rooney, actor: born Brooklyn, New York 23 September 1920; married 1942 Ava Gardner (divorced 1943), 1944 Betty Jane Rase (divorced 1949, one son, one son deceased), 1949 Martha Vickers (divorced 1951, one son), 1952 Elaine Devry (divorced 1958), 1958 Barbara Ann Thomason (died 1966, one son, three daughters), 1966 Marge Lane (divorced 1967), 1969 Carolyn Hockett (divorced 1975, one adopted son, one daughter), 1978 Jan Chamberlin; died North Hollywood, California 6 April 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments