Michel Bacos: French pilot who refused to abandon his Jewish passengers in 1976 Entebbe hijacking

With the world watching, 100 Israeli commandos travelled to Uganda to conduct one of the most daring rescue missions ever

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

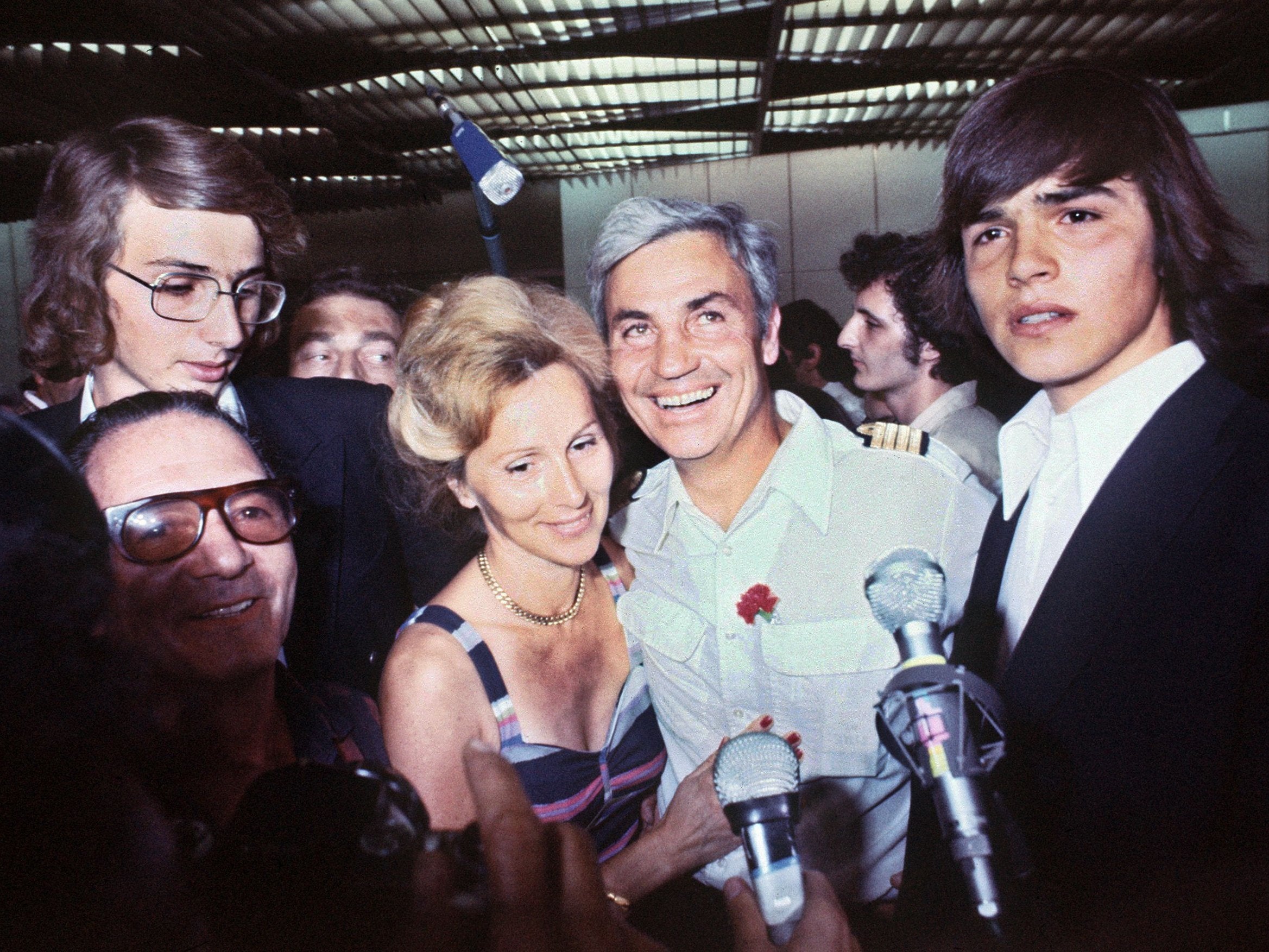

Your support makes all the difference.When Michel Bacos’ plane was taken over by hijackers who forced him to fly Uganda’s Entebbe airport in 1976, the French pilot refused to abandon his Jewish passengers – who had become hostages.

What began as ordinary flight on 27 June, with magical views of the Mediterranean sea, quickly became terrifying after Air France Flight 139 made a scheduled stop in Athens, heading to Paris from Tel Aviv.

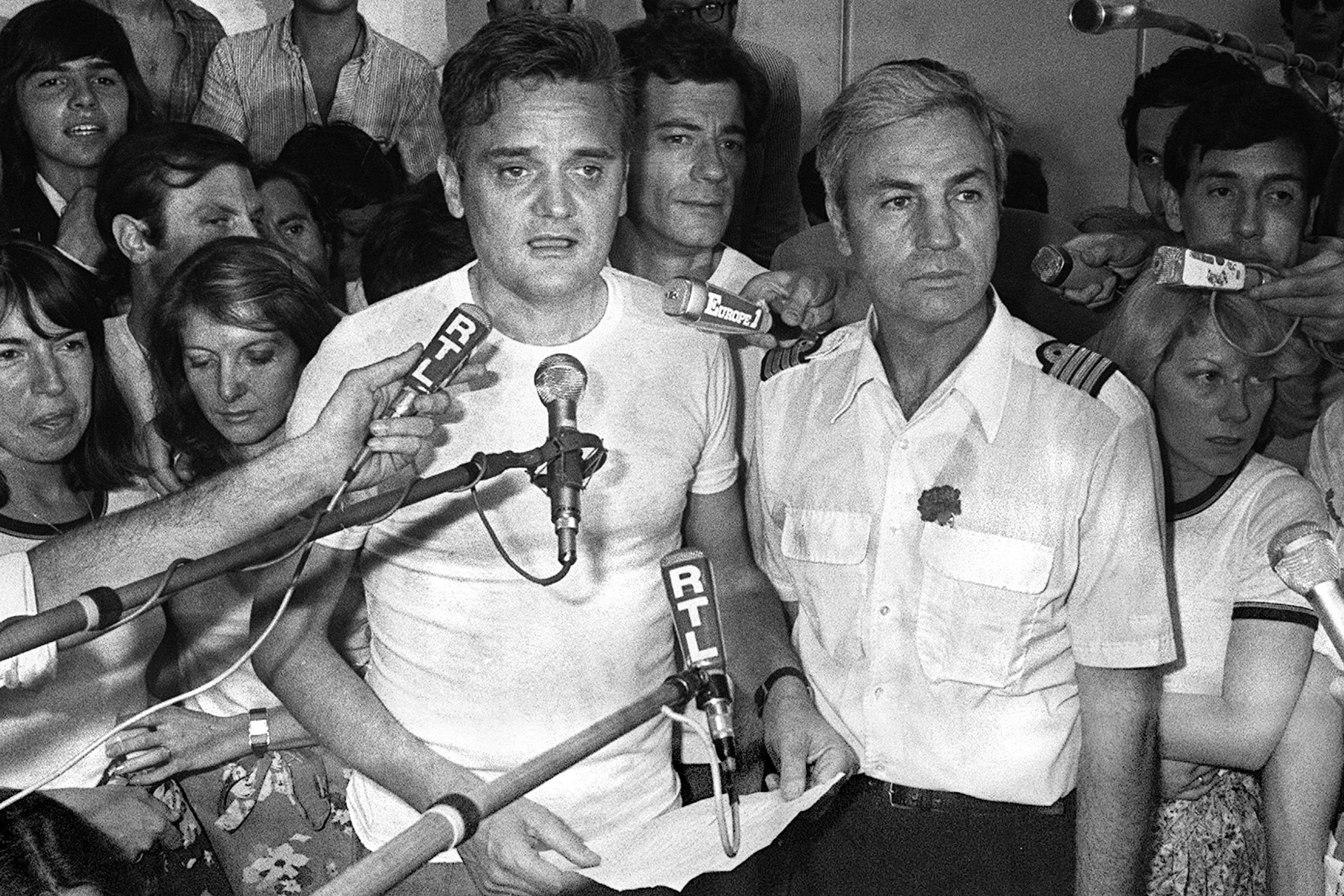

“Eight minutes after the takeoff from Athens, I heard noise in the passenger cabin, then screams,” Bacos recounted shortly after the events, according to an account published in the New York Times.

“First I thought there was a fire on board. The chief engineer opened the door of the pilot’s cabin and found himself nose to nose with the chief hijacker” – who was brandishing a pistol and a grenade.

A group of guerrillas associated with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and a radical German group had boarded the plane in Athens. One of them pointed a gun at Bacos’ head. “Every time I tried to look in a different direction, he pressed the barrel of his gun against my neck,” Bacos recalled.

Onboard were 248 passengers and 12 crew. Bacos was ordered to divert the plane to Benghazi for refuelling. From there it flew to Entebbe where the passengers and crew were marooned in an old, empty terminal. They endured six days of captivity before being freed in one of the most daring rescue operations ever.

Among the passengers, who had been on their way to vacations, family visits, weddings and bar mitzvahs, was at least one Holocaust survivor. Fear escalated when the terrorists separated the Jews and Israelis from the rest of the group, a move that recalled the selections conducted in Nazi death camps.

“I’m responsible for all of the passengers and demand to be able to see all of them – be they Israeli or not – at any given moment,” Bacos recalled insisting. The captors assented and he was “able to go from one hall to the other without receiving permission, every time.”

When the roughly 150 non-Jewish hostages were released, Bacos and his crew were invited to go with them but declined.

“There was no way we were going to leave – we were staying with the passengers to the end,” he said. “This was a matter of conscience, professionalism and morality. As a former officer in the Free French Forces, I couldn’t imagine leaving behind not even a single passenger.”

The crisis ended when dozens of Israeli commandos stormed the airport by night, arriving in a motorcade disguised to look like that of Ugandan leader Idi Amin. Three hostages, seven terrorists and 20 Ugandan soldiers were killed in the operation. Another hostage, who had been taken to a Ugandan hospital, was later murdered.

On their flight back to Israel, the commandos found Bacos seated next to the body of unit commander Yonatan Netanyahu – older brother of Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu – who was killed in the rescue operation. Such was their admiration for the pilot that they called him forward on the plane. “Your place is not here,” he said one of them told him, “but in the cockpit.”

Bacos was born in Egypt, where his father worked at the Suez Canal. He became a pilot after serving in the Free French Forces under Charles de Gaulle during the Second World War.

In the early years of his flying career, Bacos flew between West Berlin and West Germany, according to Ynetnews. His wife, Rosemary, was a German flight attendant. Besides his wife, survivors include three children.

Upon his return from Entebbe, Bacos said that he took two weeks of vacation, then insisted that his first flight be to Israel, to see if he was “still afraid”. He was not, and continued flying until his retirement in 1982.

He is a recipient of the Legion of Honour, France’s highest decoration, awarded for his courage in Entebbe.

On news of his death Benjamin Netanyahu wrote on Twitter: “I bow my head in his memory and salute Michel’s heroism.”

Michel Bacos, French airline pilot, born 23 May 1924, died 26 March 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments