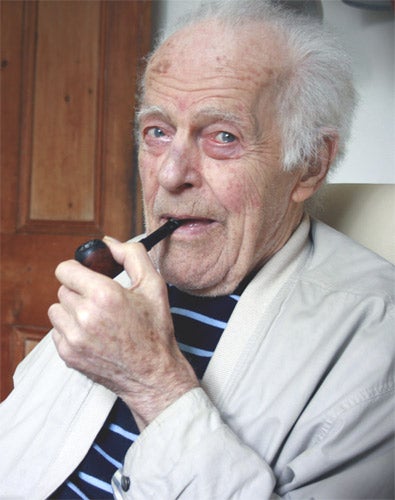

Michael Kidner: Pioneering Op artist inspired by mathematics who strove to eliminate subjectivity from his work

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Marion Frederick, an American actress, wed her husband in London in 1949, a friend of the groom shook her warmly by the hand and said, "Congratulations! You have married the most well-mannered man in England." That man was the artist, Michael Kidner, whose death brings to an end an era in British painting and, possibly, in British politeness.

Good manners and artistic bent do not always go hand in hand, but in Kidner's case they were specifically allied. If his work is usually described as Op Art – Optical artists play tricks on the eye with geometric shapes – then it might more properly be seen as Systems Art. Broadly, Systems artists imitate the self-propagating processes of nature – cellular reproduction, say, or the formation of shells – to make work which generates itself. Thus Kidner's Four Colour Wave (1965), in the Tate Collection, works out colour and form as a kind of algorithmic equation, proceeding from A to Z by a set of rules which the picture itself purports to provide.

By working in this way, all Systems painters – Kenneth Noland's '60s chevron pieces are probably the best-known Systematic works – aim to eliminate subjectivity from art, and with it signs of their own hand. In Kidner's case, this self-effacement seemed part of that almost painful British politeness remarked upon at his wedding – a reticence instilled in him by another system, now pretty well extinct, based on class, education and a belief in the virtues of modesty. He wanted his waves, he said, to come to their own end rather than to his. To impose a conclusion on them would be to "express the personal taste of the artist," an indulgence Kidner abjured.

Born into a family of well-to-do Midlands industrialists, Michael Kidner was a sickly child: a streptococcal infection nearly killed him at the age of nine, and he was bed-ridden for a year. To toughen him up, he was sent to Pangbourne Nautical College, a notoriously robust school founded to turn out naval officers. (The soldier and SOE operative, David Smiley, the inspiration for John Le Carré's eponymous hero, was a contemporary.) Later, Kidner, much bullied, recalled that, "At Pangbourne I became very turned-in. I think maybe the habit persisted."

After his father's death in a motorcycle accident when he was 14, he was sent to Bedales. The more liberal regime there suited him better, and he passed his exams for Cambridge, going up to read history in 1936. On a visit to a sister in America after graduation, he was trapped by the outbreak of war. Crossing the border, he joined the Canadian Army and served in France after the D-Day landings.

It was only on his return to Britain in 1946 that Kidner took up art. At the age of 30 he travelled to Aix-en-Provence to paint in Cézanne country, meeting the Cubist artist and teacher, André Lhote. By now, he had also met Marion Frederick, who pushed him to continue his studies with Lhote in Paris. This was to set a pattern in their marriage which would persist until her death in 2003.

If Marion Kidner had wed the most well-mannered man in England, she had little time for politeness herself. Outgoing and abrasive, her style was a perfect foil for her husband's. Although there is little doubt that some gallerists were put off by her manner – a feud with Robert Graves, a neighbour in the Majorcan village of Deya, lasted for decades – it also provided the necessary dash of aggression missing in Kidner himself. It was Marion Kidner, for example, who invited the film-maker, Peter Sykes, to shoot The Committee in the basement of the couple's Belsize Park house in 1968, thus ensuring them a walk-on part in Pink Floyd's first movie.

With his wife handling the harsher realities of the art world, Kidner could concentrate on making work that was, like himself, ever more self-contained. From the 1970s on, his self-perpetuating mathematical systems came to include forms such as the stripe, the pentagon and the column; an early proponent of computers in art, he experimented with computer-aided design. For all their esoteric underpinnings, the works that resulted were often suffused with an emotionalism Kidner found difficult to express in life. One deeply moving silkscreen, Requiem, recalls the death of his adopted son, Simon, known as Og, in a motorcycle accident in 1982.

If his paintings gained recognition abroad, particularly in Poland and Germany, they tended to be eclipsed at home by the showier images of Op artists such as Bridget Riley. The Tate bought mostly works on paper, and none of these after 1984. It was only in 2004, at the age of 87, that Kidner was finally elected a Royal Academician. His wife, who dyed her hair turquoise in the late 1990s, had died the year before, and Kidner himself had recently been diagnosed with cancer. Despite suffering from a nervous condition which robbed him of the us e of his legs, he continued to paint, with the help of an assistant, until the day of his death.

In an interview a decade earlier, Michael Kidner had summed up his attitude to art (and, perhaps, to life) thus. "Expression," he said, "exists in all of us, so why single it out as if to say, I'm the one? For me, I can only be expressive when I'm not being self-conscious. Or, you know, attempting to be."

Charles Darwent

Michael Kidner, artist, born Kettering, Northamptonshire 11 September 1917, married 1949 Marion Frederick (died 2003; one adopted son, deceased); Royal Academician, 2004; died London 29 November 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments