Michael Hastings: Writer best known for 'Tom and Viv'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

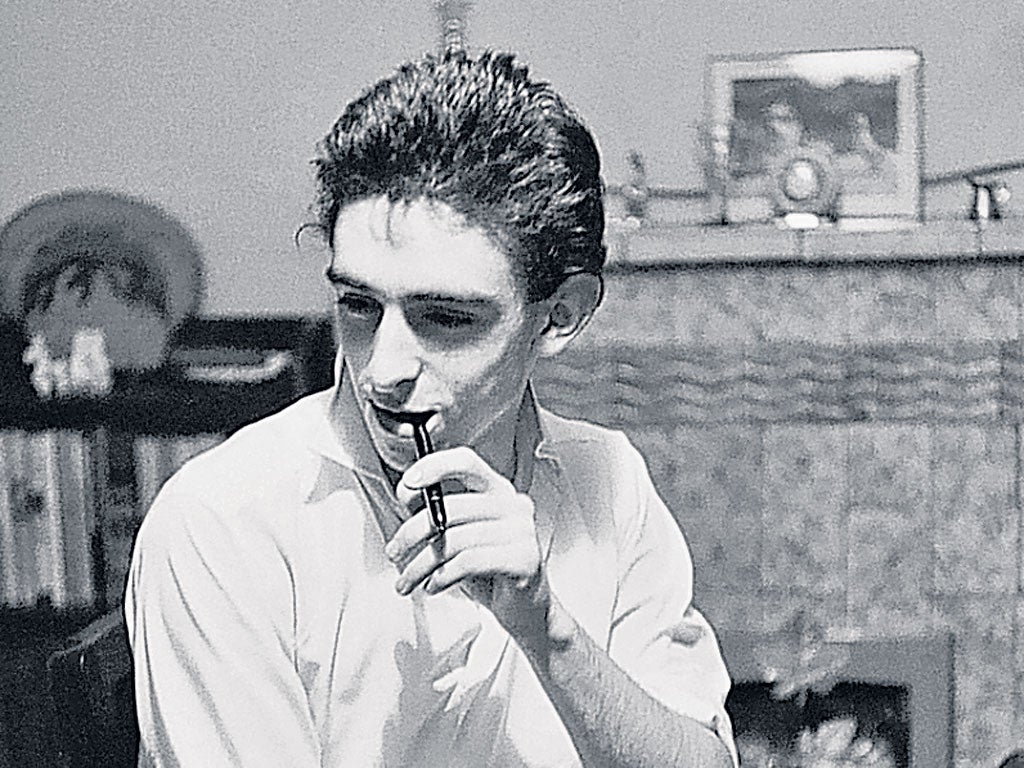

Your support makes all the difference.Precocious success can prove a mixed blessing in the theatre. Michael Hastings had three playsproduced in London before his 20th birthday, but with the exceptions of his exuberant Gloo Joo (1977) and Tom and Viv (1984),a moving scrutiny of TS Eliot's troubled first marriage, too much of his later career – never predictable and always intriguing – was often unfairly scarred by ill luck.

The London-born Hastings had a colourful early life, educated by his forceful mother in her Brixton council flat and, less inspiringly, at various south London schools. He began an apprenticeship to a tailor at the age of 15, juggling work with his sporting ambitions (he was a keen boy boxer and runner), although even then he had a voracious love of literature and the theatre; much of his meagre wages went on London theatre tickets, walking home afterwards to south London.

He was 17 when the enterprising "off-West End" New Lindsey Theatre produced Don't Destroy Me (1956), which drew heavily on his apprenticeship training. It was set in a tailor's shop, his sinewy dialogue yoked to a tender picture of an adolescent boy and girl struggling to break free from a suffocating environment; it marked him as a rising talent. George Devine, then just getting underway with the English Stage Company at the Royal Court, responded instinctively to Hastings' vibrant commitment, taking him on as a raw actor-writer and paying him (just) a living wage. Hastings would joint the queue for wages each Friday, mixing with other then-unknowns such as John Osborne alongside farouche West End veterans like Esme Percy – all meat and drink to a stagestruck teenager.

The Court's early programming included a Sunday-night performance without décor of Yes and After (1956), Hastings' controversial play tracing the catatonic effects of rape on a vulnerable girl. Kenneth Tynan was one of several critics to praise the piece.

In The World's Baby (1958), Hastings took on a much broader canvas for his panoramic portrait of a young woman and her son, moving from the Spanish Civil War to Suez. Economics allowed, again, only for a Court Sunday-night showing; both the play and the central portrait of Anna were praised but a subsequent production never crystallised and it remains a kind of "lost play".

Hampstead Theatre programmed Hastings' Lee Harvey Oswald (1966), a sober, unsensational study of the assassin's mind. He returned to Sloane Square with For the West (1977), a tough piece laced with dark comedy focused on the expulsion of Indians from the gruesome regime of Amin's Uganda. Back at Hampstead he had a happy time with Gloo Joo (1977); this punchy, ebullient comedy centred round the ruses of a West Indian dodging deportation enjoyed further success in the West End (Criterion), winning the Evening Standard Best Comedy award.

With Full Frontal at the Royal Court (1979) Hastings pulled few punches – several reviews labelled it "Swiftian" – in a powerful monologue from a young Nigerian betrayed by his friends and driven into an application to join an extremist party of the right. Another Royal Court success came with Tom and Viv (1984), his exploration of the emotional pressure chamber of Eliot's marriage to the tragic Vivienne Haigh-Wood (mesmerisingly played by Tom Wilkison and Julie Covington). The play's understat ed humanity was reinforced in its 2007 revival at the Almeida.

Jonathan Miller collaborated happily with Hastings on the dramatist's version of Ryszard Kapuscinski's The Emperor (Royal Court, 1987), mining recurrent themes of imperialism and the corruption of power. But changing regimes at the Court seemed less hospitable to Hastings. He was invited to work on Ariel Dorfmann's own basic translation of his Death and the Maiden (1991) but he felt that his contribution became decidedly downplayed.

It appeared that the Royal Shakespeare Company might provide a congenial new Hastings haven. The company produced A Dream of People (1990), featuring a striking early Toby Stephens performance in the Jean Renoir-ish country house comedy, and his final major play was an RSC commission. However, Calico became time-consumingly snarled up in the company's planning; it was finally dropped, then taken up for an ill-starred West End production (Duke of York's, 2005). An impressive young Romola Garai as James Joyce's troubled daughter was one of the few redeeming features in a misbegotten, vapid commercial flop.

Ill-fortune also marked some of Hastings' other work. For television he was commissioned by Channel 4 and came up with some of his best work in the two-part Soho, vividly vernacular with a rich range of characters. It was greenlit one Friday, but a change of regime saw its cancellation. It is hardly surprising then, that as script editor Hastings was so crucial with Simon Curtis to the BBC's Performance series (1990-91). Championing work overlooked or jinxed, it included treats such as Les Dawson's sausage-chomping performance in drag as the matriarch in Nona (Hastings' version of Roberto Cossa's original) and Absolute Hell, a notorious 1947 flop later later reclaimed by the Orange Tree Theatre prior to its National Theatre revival with much of the television cast, led by Judy Dench.

Hastings' appetite for work never diminished. For the cinema he provided the screenplay for one of Michael Winner's better films in a kind of "prequel" to Henry James' The Turn of the Screw in The Night Comers (with Marlon Brando), reinforcing his appreciation of James with a fine BBC television adaptation of The Americans with Diana Rigg. On radio he provided a string of outstanding adaptations, from The Leopard to Tender is the Night and, more recently, a five-part adaptation of Irene Nemirovsky's Life of Chekhov.

A gifted biographer with a special sympathy for lives lived beyond conventional boundaries, Hastings wrote an absorbing study of Rupert Brooke in The Handsomest Young Man in England (1967) and an equally distinctive voyage round that most intrepid of explorers, Richard Burton in Burton: A Biography (1978) – an ideal subject for an always questing imagination.

Michael Gerald Hastings, writer: born London 2 September 1938; married firstly (one daughter and two sons), 1975 Victoria Hardie; died 19 November 2011.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments