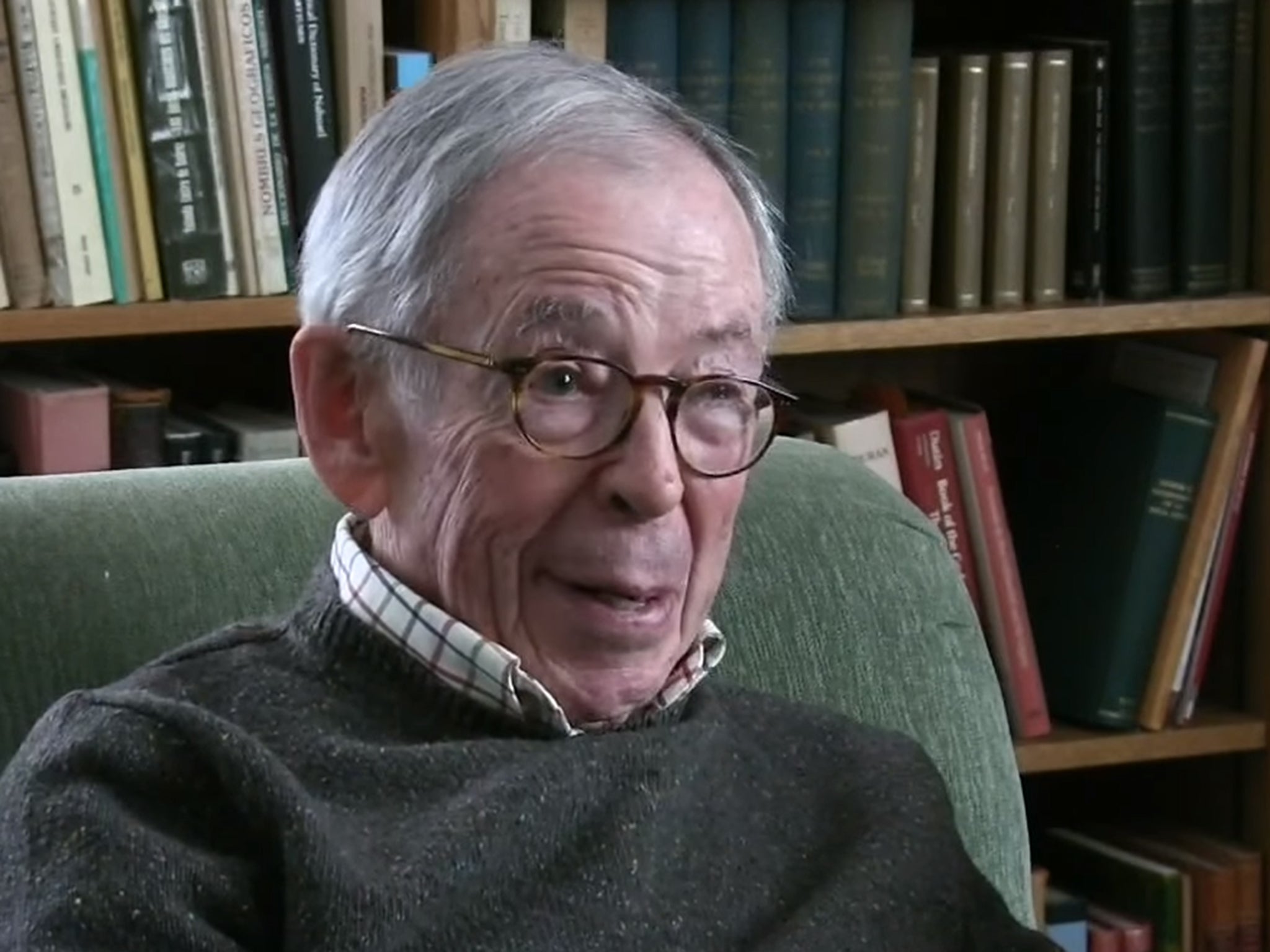

Michael Coe: Archaeologist who shone a light on the Maya civilisation

He made a major contribution to the decoding of Maya writing and art, and did much to popularise his field

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Michael Coe, who has died aged 90, was an archaeologist, anthropologist and authority on ancient Mesoamerican civilisations who led excavations in Guatemala and Mexico, helped to decode Maya writing and art, and wrote bestselling books that galvanised public interest in his field.

Driven by a sense of adventure, Coe worked as a CIA officer in Taiwan before beginning his archaeological career in Guatemala in the mid-1950s, excavating a site on the Pacific Ocean that was previously ignored – in part because of the sweltering heat and mosquitoes. He returned to the United States one Christmas and spent most of the holiday in bed, recovering from malaria.

Later, digging in the dirt of San Lorenzo, near the Gulf of Mexico in Veracruz, Coe unearthed colossal stone heads and monuments left behind by the Olmec, a civilisation he helped to date, tracing its roots back more than 3,000 years. He also deciphered the meaning of cryptic Maya ceramics and writing symbols, or glyphs, and drew attention to a bark-paper document known as the Grolier Codex, generally considered one of four surviving Maya manuscripts, or codices.

Based at Yale University for 34 years before retiring in 1994, Coe taught thousands of students and wrote for an audience that ranged from academics and armchair historians to archaeological junkies and tourists to Mexico. His books included Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs (1962), The Maya (1966) and Breaking the Maya Code (1992), the last of these chronicling the years-long effort to crack the Maya script, a mammoth undertaking aided by Coe and his wife Sophie.

Coming of age in an era before most scholars were siloed in narrow academic disciplines, his work ranged far beyond the Maya. He was a scholar of Angkor Wat and the Khmer civilisation in southeast Asia, excavated a colonial-era fort near a farm he owned in the Berkshires of Massachusetts, and became a historian of fly-fishing, a hobby he pursued obsessively from Labrador to Siberia.

For a time, he accompanied his wife on trips to Europe, where she pored over 400-year-old texts while preparing a comprehensive history of chocolate. After his wife was diagnosed with cancer in March 1994 (she died two months later), Coe promised to complete what became The True History of Chocolate, and was listed as junior author when it was published in 1996.

Coe was perhaps an unlikely candidate for scholarly work. Raised in wealth and privilege on the Gold Coast of Long Island, New York, he was the great-grandson of Standard Oil executive Henry Huttleston Rogers, a builder of the Virginian Railway, for which Coe’s father was vice president.

He had initially planned to become a writer, studying English at Harvard before a visit to the Maya ruins of Chichen Itza steered him towards anthropology. Then a professor asked if he’d “like to work for the government in a really interesting capacity” – a suggestion that launched his brief career in the CIA.

Coe was sent to Taiwan to join Western Enterprises, a front organisation that aimed to subvert Mao’s communist government in China. “The whole operation was a waste of time,” Coe said. Within a few years he was back at Harvard, studying for his doctorate.

Coe was a keen and fearless adopter of new techniques: for example, he championed an emerging approach known as ecological archaeology, studying the ways in which ancient peoples related to their environment.

He risked his career in the 1960s to back the findings of Soviet linguist Yuri Knorozov, who argued (correctly) that the Maya writing system had a phonetic component. In the face of opposition, Coe threw his support behind Knorozov and co-wrote a 1968 article in which he translated the glyph for cage, showing how it contained individual syllables.

Coe was also closely identified with the Grolier Codex, which was said to have been found in a cave near Tortuguero, Mexico, before being acquired by a collector and displayed at a 1971 art exhibition organised by the Grolier Club in Manhattan.

Scholars questioned its authenticity. Coe acknowledged that the document was a “hot potato” but proclaimed he would stake his professional reputation on it. Three other Maya books were known to have survived through the centuries, and countless texts had been destroyed by conquistadors and Catholic priests.

In 2016 a team of Mayanists including Coe conducted an analysis that supported the Grolier Codex’s authenticity. Two years later, researchers from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History reached the same conclusion – a vindication for Coe.

Michael Douglas Coe was born in Manhattan in 1929. He grew up in Oyster Bay, New York, on a 400-acre family estate known as Planting Fields, now a state park. Coe studied at St Paul’s preparatory school in Concord, New Hampshire, before entering Harvard. He joined the Yale faculty in 1960 and later chaired the anthropology department.

Coe’s many areas of expertise included the collapse of civilisations, and he sometimes noted that most lasted around 600 years – roughly the length of time since western civilisation flowered during the Renaissance. Environmental destruction and burgeoning population growth helped fell the Maya, he once said, and remained serious concerns across the planet.

“The difference is we have a choice whether to let things get worse or fix them,” he said. “That’s what science is about. But it takes will on the part of those who govern and those who are being governed. To tell you the truth, I don’t know if we have that.”

He is survived by five children.

Michael Coe, archaeologist and anthropologist, born 14 May 1929, died 25 September 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments