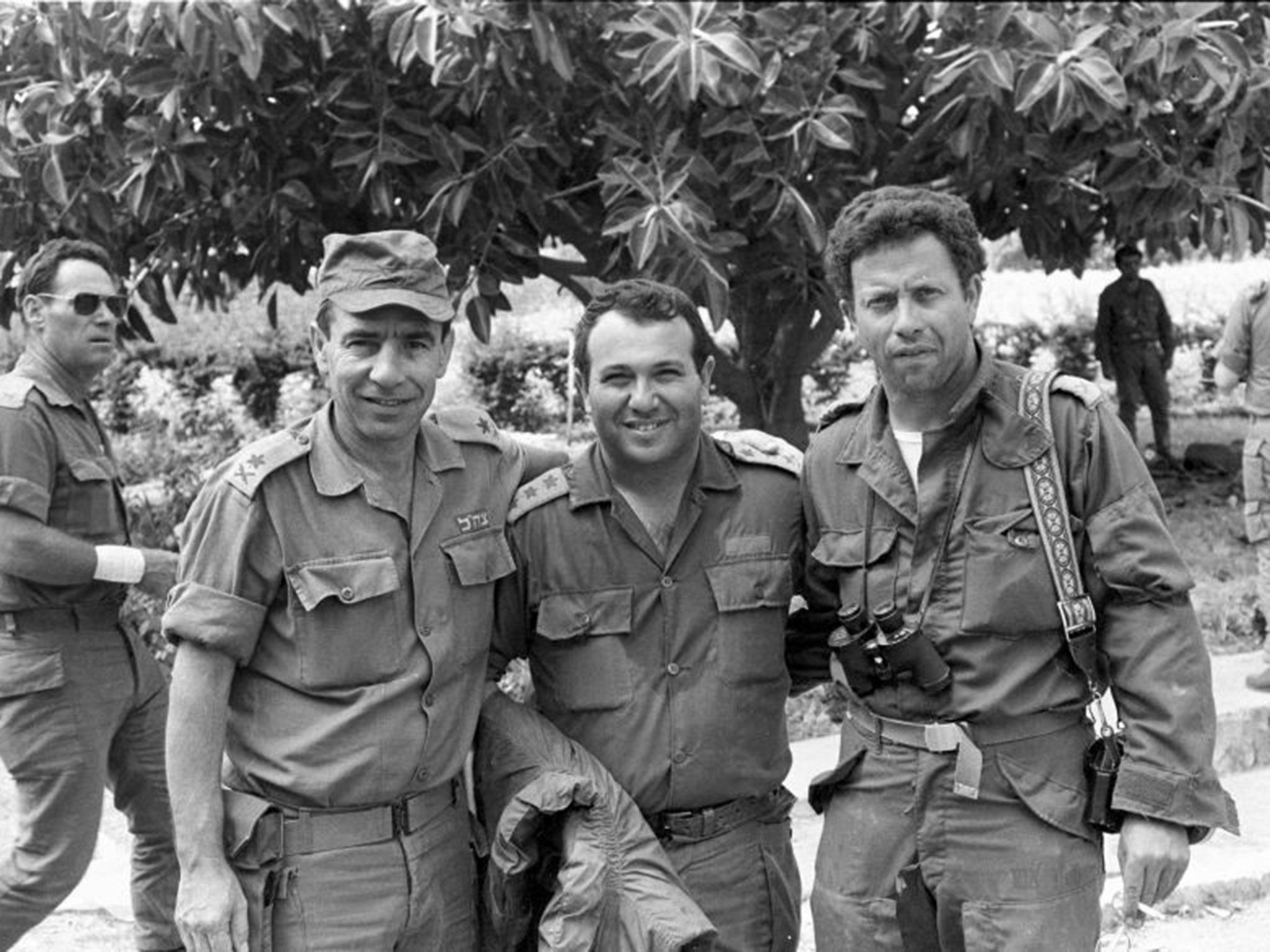

Meir Dagan: Army general who became a Mossad chief lauded for his ferocity but who later criticised Israel’s policy towards Iran

Dagan was reported to have employed techniques including car bombing and poisoning, and was regarded as one of the most effective leaders in the history of Mossad

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Meir Dagan, who has died of cancer, was the long-serving chief of Israel’s Mossad spy agency who was widely admired in his country for directing assassinations and acts of sabotage that helped defuse threats that included the Iranian nuclear programme. The Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu – recently the target of fierce criticism by Dagan over Israeli policy toward Iran – lauded the former spymaster as a “daring fighter and commander who greatly contributed to the security of the state in Israel’s wars.”

Even among the commandos of Mossad and the Israel Defence Force, where he rose to major general, Dagan stood out for the fierceness of his dedication. Prime Minister Ariel Sharon appointed Dagan to his Mossad post in 2002, charging him with giving the espionage agency “a knife between its teeth.”

Less than a decade later, Netanyahu observed that Dagan’s impact had been even greater than Sharon expected. “Some people have a knife between their teeth,” Netanyahu remarked when Dagan stepped down. “Meir has a rocket-propelled grenade between his teeth.”

Dagan was reported to have employed techniques including car bombing and poisoning, and was regarded as one of the most effective leaders in the history of Mossad, whose earlier exploits included the capture in Argentina in 1960 of Adolf Eichmann, the SS official who was a principal architect of the Holocaust. Eichmann was later tried and executed in Israel.

Mossad is shrouded in secrecy, but news reports linked the agency, under Dagan’s leadership, to operations that included the car bombing in Damascus in 2008 that killed Imad Mughniyah, a Hezbollah leader. The CIA reportedly helped target Mughniyah, who was tied to attacks on the US Embassy in Beirut and Israel’s Embassy in Argentina.

Dagan was said to have directed the agency’s activities mainly toward Iran, and during his leadership the Iranian nuclear programme encountered laboratory fires, equipment malfunctions, plane crashes and Stuxnet, a destructive computer virus. Iranian scientists were also killed. “Without this man the Iranian nuclear programme would have taken off years ago,” reported the Egyptian daily Al-Ahram, which described him as “Superman”.

At times during Dagan’s leadership, perhaps emboldened by its successes, Mossad appeared brazen. The agency was linked to the assassination in 2010 of Mahmoud al-Mabhouh, a Hamas leader, at a hotel in Dubai. The alleged assassins carried false foreign passports – a detail that created a diplomatic stir – and were caught on camera disguised in tennis gear that appeared to lack the usual Mossad sophistication.

Dagan enjoyed considerable clout in Israel – Netanyahu would visit his office, rather than vice versa, but after leaving office, Dagan became an outspoken critic of the prime minister for dangling the possibility of an Israeli military strike on Iran. He drew worldwide notice in 2011 when he said that such a plan would be a “stupid idea” that could precipitate a protracted conflict. He instead supported covert action in Iran. In 2015, he criticised Netanyahu’s opposition to the Iranian nuclear deal.

“Israel is a country surrounded by enemies, but the enemies do not scare me,” he said at a rally in Tel Aviv’s Rabin Square in March 2015, shortly before the elections in which Netanyahu was elected to a fourth term. “I am scared of our leadership.”

Dagan was born Meir Hubermann in 1945 in Kherson, Ukraine and traced his zeal for Israel to the Holocaust. He kept in his office a photograph of a Jewish man, draped in a prayer shawl, kneeling with his hands raised before two Nazis. The man was his grandfather, about to be killed.

As a boy, Dagan moved to Israel with his parents, who opened a laundry near Tel Aviv. Leaving school, he joined the military and soon became known for his mettle. One comrade recalled that during his free time Dagan would throw knives at trees and telephone poles. He was wounded twice in battle, including during the Six-Day War of 1967.

In the 1970s, Sharon, then general of the southern command, selected Dagan to lead a special forces unit in Gaza. Dagan formed a group who disguised themselves as Palestinians to apprehend or kill enemies. Once, his men rode a fishing boat into Gaza and assassinated a group of PLO operatives.

After his military career, Dagan served in Israel’s counter-terrorism bureau, eventually leading the organisation, and on the IDF’s General Staff before joining Mossad. As hobbies, Dagan collected swords and painted.

When Dagan retired from Mossad, the Jerusalem Post reported that “none of his predecessors can match, nor is it likely that any of his successors will equal, the daring and sheer volume of the covert operations he launched against his chosen targets.” By their nature, many of those operations will remain unknown. “Israelis,” the former prime minister and defence minister Ehud Barak once said, “owe Meir Dagan a great debt of gratitude even though we cannot tell them all the reasons why.”

EMILY LANGER

Meir Hubermann (Meir Dagan), soldier and intelligence official: born Ukraine 30 January 1945; died 17 March 2016.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments