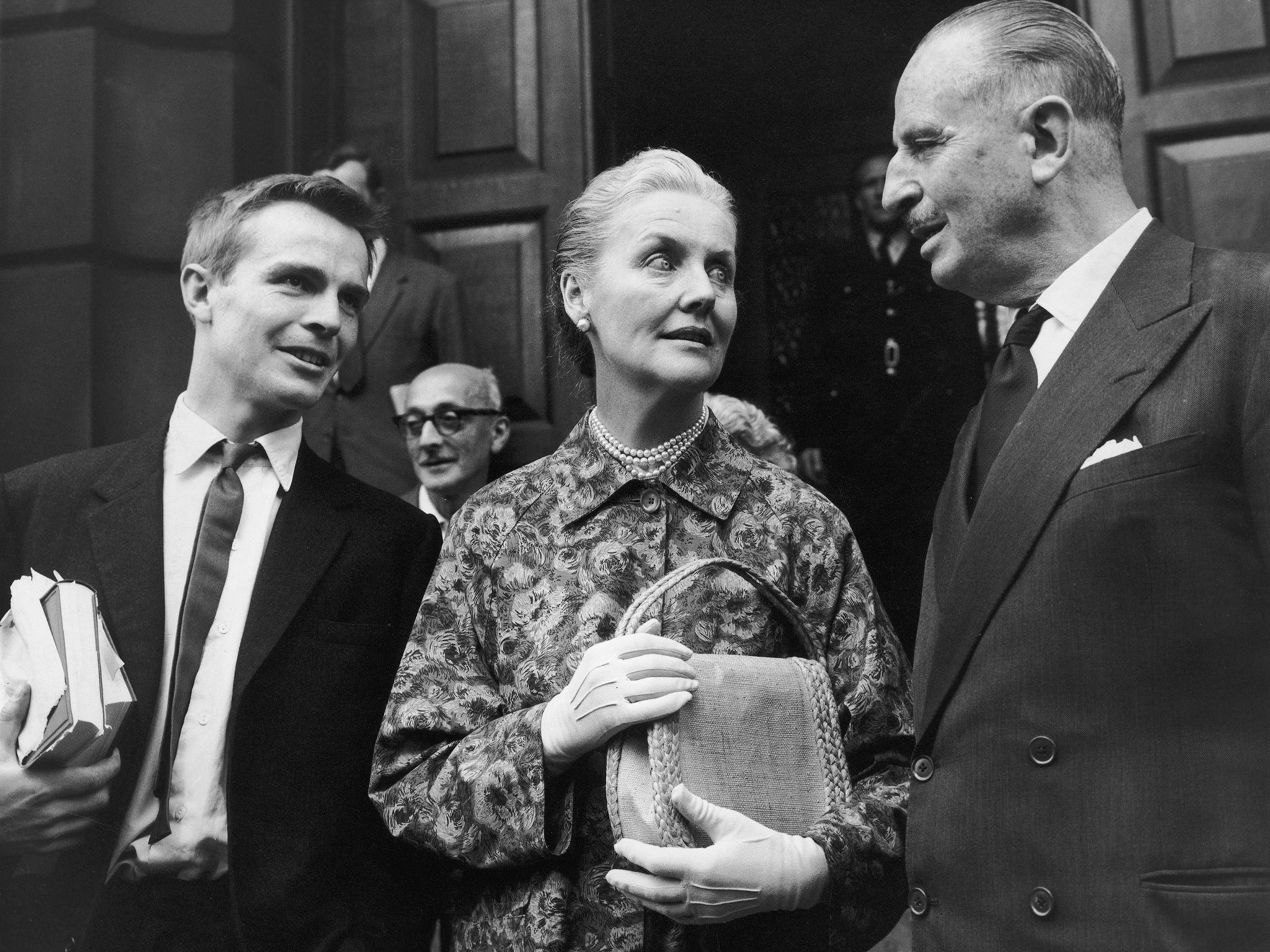

Max Mosley: Godfather of Formula One who transformed racing

The son of a fascist leader and a Mitford sister, the lawyer turned racing chief struggled for many years to shake off the shadow of his ‘antecedents’. But his life proved to be fascinating in its own right

Max Mosley, who has died of cancer aged 81, led a colourful life. He was born the son of British Union of Fascists (BUF) leader Sir Oswald Mosley, masterminded a transformation of the high-octane sport of motor racing, and successfully sued the News of the World after it published lurid allegations about him.

His charm and legal brain combined with the streetwise negotiating skills of Bernie Ecclestone to form a partnership. As bosses of Formula One, they turned the sport into a commercial giant, implemented better safety standards on the track, and helped Mosley to liberate himself from his family background.

Max Rufus Mosley was born in London in April 1940, seven months after the outbreak of the Second World War. Within weeks, both his father, a former Conservative and Labour MP who became disillusioned with mainstream politics, and mother, Diana, third of the six famous Mitford sisters, were interned by the British government in Holloway Prison because of their fascist views, and the BUF blackshirts were banned.

When his parents eventually moved abroad, Max was brought up in Ireland and attended schools in France and Germany before enrolling at Millfield, Somerset.

He gained a degree in physics from Christ Church, Oxford, where he was secretary of the student union, and where he met Jean Taylor, whom he married in 1960, a year before his graduation. While there, he also watched motor racing for the first time, at the nearby Silverstone circuit.

Then, he studied law at Gray’s Inn, London – at the same time serving in the Territorial Army’s Parachute Regiment (1961-64) and canvassing for his father’s far-right Union Movement. He qualified as a barrister in 1964 and practised as a specialist in patent and trademark law.

Mosley taught law in the evenings to save up enough money to start racing cars himself. He took part in more than 40 races in 1966 and 1967, winning 12 of them.

The following year, he co-founded with Chris Lambert the London Racing Team to compete in the newly launched European Formula Two championship. Tragically, within months, Lambert died in a racing accident.

Then, Mosley moved to Frank Williams’s F2 team before retiring from racing in 1969 – after two accidents in his own Lotus – to form March Engineering with three others to manufacture racing cars. He looked after the commercial and legal side of the business and Jackie Stewart became its most high-profile driver, but the company’s initial success in Formula One ebbed away.

In 1977, Mosley sold his shares and became legal adviser to Foca (the Formula One Constructors’ Association), which he had founded with Bernie Ecclestone three years earlier to represent British racing teams in negotiations with F1’s governing body, the FIA (Federation Internationale de l’Automobile).

The pair spent the next few years battling over television and commercial rights. The teams threatened to form their own breakaway championship before Fisa (the Federation Internationale du Sport Automobile) – an autonomous sub-committee delegated by the FIA to oversee motorsport – accepted the Concorde Agreement of 1981.

This opened up commercial opportunities, including bigger sponsorships, and paved the way for Ecclestone – whose new Formula One businesses managed TV rights – and Mosley to become the godfathers of the sport.

Mosley’s rise was rapid. He became president of, successively, Fisa’s Manufacturers’ Commission in 1986, Fisa itself in 1991, and the FIA in 1993. His only disappointment during that period was that his political ambitions were thwarted by his failure to be chosen as a Conservative candidate in the 1983 election. By the late 1990s, he was a donor to Tony Blair’s Labour government.

Alongside the commercial improvements in motor racing, his modernising and restructuring included improving safety in the wake of Ayrton Senna’s death in the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix.

Engine powers were reduced, new protections for drivers introduced, and a carbon-neutral policy adopted, and there was major investment in purpose-built Grand Prix venues, such as in Shanghai.

Not so popular with F1 teams was his 100-year extension of TV rights to Ecclestone’s companies for just $360m.

In 2008, after the News of the World filmed Mosley with five prostitutes in what it described as a “sick Nazi orgy” with German military uniforms and concentration camp-style pyjamas, Mosley successfully sued the paper for breach of privacy, and a High Court judge ruled that there was no Nazi element.

“All my life, I have had hanging over me my antecedents, my parents, and the last thing I want to do in some sexual context is be reminded of it,” he told the court.

After stepping down as FIA president the following year, Mosley supported the Hacked Off pressure group and paid the court costs of some claimants alleging their phones had been hacked by the News of the World.

His autobiography, Formula One and Beyond, was published in 2015.

Mosley’s wife and their son Patrick survive him. Their other son, Alexander, died of a drug overdose in 2009.

Max Mosley, lawyer and motor racing executive, born 13 April 1940, died 23 May 2021