Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

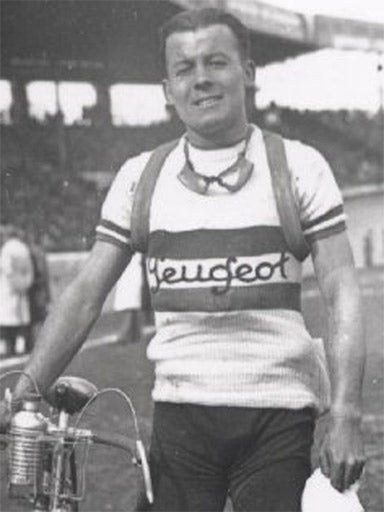

Your support makes all the difference.Known as the "little Napoleon", the cycling team director Maurice de Muer was one of France's leading sports managers of the 20th century – and someone to whom English-speaking cycling fans, even 30 years after his retirement, still owe a special debt. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, in his final years of three decades of directing, De Muer ran the prestigious Peugeot professional squad. Partly thanks to him, Peugeot's ACBB amateur "feeder" team opened its doors to a mainland European squad's first large-scale recruitment of young Anglophone riders – a key moment in a sport in which previously, barring a few notable exceptions, making a go of it on the far side of the Channel had seemed all but impossible.

ACBB and Peugeot paved the way for riders like Ireland's first Tour winner, Stephen Roche, Robert Millar – still Britain's greatest stage racer – the Australian pioneer Phil Anderson and before that, in 1974, Jonathan Boyer, the US's first rider in the Tour.

These were the names that regularly made headlines: for diehard British cycling fans in the 1980s, it was common knowledge that a host of other middle-ranking GB pros like Graham Jones, Sean Yates and John Herety, as well as the Australian Allan Peiper, had also gone through ACBB and, mostly, Peugeot. And the "Foreign Legion", as they were nicknamed, in turn laid the foundations for the wave of successful English-speaking pros of the last two decades, from Lance Armstrong through to Bradley Wiggins and Mark Cavendish.

As Peugeot's manager, De Muer was responsible for the final part of the production line. But he had some ingrained prejudices, too, which limited the progress of riders he had hitherto indirectly assisted. "He hated my guts because I was small and he liked big guys," Millar said in 1993. As a result, Millar was not selected for two Tours de France early in his career.

Others, like Bernard Thévenet, who won two Tours under De Muer's guidance in 1975 and 1977, recall his volcanic temper. "Regularly, he would go absolutely livid for 15 minutes," Thévenet said, "but then he would calm down again for a long period of time."

De Muer's all-powerful, arbitrary approach to directing provoked strong reactions, to the point where some of his more jaded riders in the early 1980s allegedly fed his wife's dog, Scotty, a sandwich with an amphetamine filling that sent the poor animal to an early grave. But there was no denying De Muer's talent. At Bic he oversaw the last big victory for the five-times Tour winner Jacques Anquetil, in the Tour of the Basque Country in 1969. At Peugeot, he was capable of guiding one of cycling's most erratic stars, the ill-fated Luis Ocaña, to a stunning Tour de France win in 1973.

Jean-Marie Leblanc, a rider at Pelforth with De Muer's first team in 1965, later a journalist and finally the Tour de France director, wrote in 1981 that: "It was an education to see De Muer at the start of a race, with his team huddled around a Michelin map, on which he had marked the day's route, the wind direction and the points to attack, like a general directing an army."

Sean Yates recalled: "He commanded respect because of Ocaña and Thévenet. He was quite intimidating, too, though, very much an old-school hard master. I remember him yelling at Phil Anderson at the start of the Milan-San Remo [the major one-day race] one year, saying, 'No, no rain jacket.' The race was 350 kilometres long, it was tipping with rain, and he didn't want Phil to have one.

"Those days, it was ca passe o ca casse [sink or swim] as a pro, there was no coaching the young riders, you fended for yourself, and Robert and Stephen kept up my morale. But the success of the teams De Muer had had spoke for itself. And at Peugeot, he was the guy on top of it all."

After retirement, De Muer bought a house at Seillans in Provence, the same village where Peugeot were based for training in the 1970s. Up until a few months ago, when his home burned down, he would still regularly go out on his bike himself.

"I remember a man passionate for cycling, having a strong desire for results... whether it was a stage of the Tour de France or the GP de Peymenade in February," Thévenet said. But for English-speaking cycling fans, the way De Muer helped lay the foundations for the breakthrough by "their" riders into the sport's continental strongholds is how he will be best remembered and appreciated.

Alasdair Fotheringham

Maurice de Muer, cyclist and team manager: born Potigny, France 6 October 1921; died Seillans, France 5 March 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments