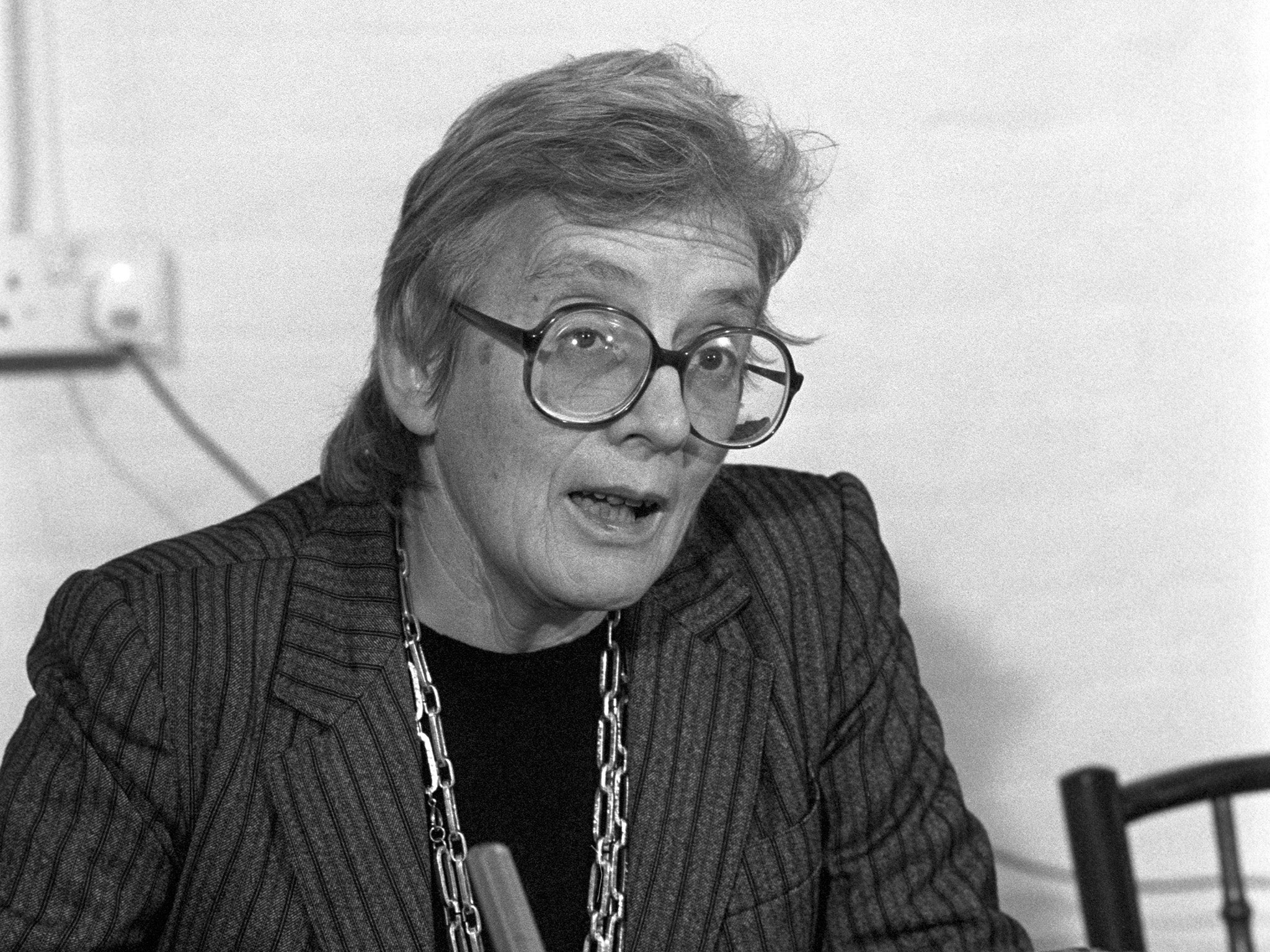

Mary Warnock: Hands-on philosopher who bridged gap between theory and policy in ethical debates

In 1984 the public intellectual, who was unafraid of controversy, led a landmark report on human fertilisation and embryology

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mary Warnock was a philosopher and ethicist who confronted some of the biggest moral issues of our times. She made significant contributions to debates surrounding life, from assisted fertilisation and embryology to assisted dying.

Warnock, who died aged 94, was born Helen Mary Wilson in Winchester in 1924. Seven months earlier her father, Archie Wilson, a housemaster at Winchester College, had died. Growing up, she had little daily contact with her mother.

Speaking about her childhood, she recalled in her memoir: “The routine was amazingly old-fashioned, even for the 1920s. Our pleasures and our security were entirely the result of the character of our nanny, Emily Coleman, who had been nanny to all of us.”

The other great influence of her early life was her sister Stephana, with whom she shared a passion for words and for music. “We both loved hymns,” she remembered fondly, “especially those that contained mysterious words like ‘paraclete’ or ‘Trisagion’.”

She was educated as a boarder at St Swithun’s School in Winchester and went up to Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, in October 1942 to study mods and greats. When the war intervened she chose to teach at Sherborne School for Girls, discovering a love for teaching.

Warnock returned to Oxford after the war and was awarded a first in greats in 1948. She married the philosopher Geoffrey Warnock the following year. During the Fifties the couple had five children, Kitty, Felix, Fanny, James and Maria in quick succession.

The subject of ethics saw a resurgence in interest in the late Fifties and early Sixties. In Warnock’s first book, Ethics Since 1900 (1960), she noted that much to her delight there were now “signs that the most boring days were over”. In her memoir, she celebrated that “at last, the absolute barrier erected by logical positivism between fact and value had been breached, and moral realism began to be sniffed in the air”.

Warnock returned to teaching in 1966, becoming headmistress of the Oxford High School, where she remained until 1972. She was appointed a member of the watchdog Independent Broadcasting Authority and became its chair in 1973, a position she held over the next decade. “It was an absurd appointment,” she commented, “because I hardly ever watched television and had not listened to commercial radio since the days of Radio Luxembourg in the nursery.”

In 1973, then-education secretary Margaret Thatcher announced that she would create a committee for the education of “children and young people handicapped by disabilities of body or mind”. Warnock was made chair of the Committee of Inquiry into Special Educational Needs, which held its first meeting in September 1974 with a large group of 27 members and a broad remit.

Writing in what became known as the Warnock Report, published four years later under a Labour government, Warnock described the scope of her review as “extending well beyond the education service”. She said: “Our terms of reference required us to take account of the medical aspects of the needs of handicapped children and young people, together with arrangements to prepare them for entry into employment.”

When the Conservatives returned to power two years later under Thatcher, the committee’s recommendations formed the basis of the 1981 Education Act, establishing new legal rights for disabled children and their parents. Today’s practice of placing children with special needs into mainstream schools and assessing them by “statementing” of their needs exists thanks to Warnock and her committee’s work.

However, in an article in The Telegraph in September 2010 – responding to a damning Ofsted report on special educational needs – she bemoaned the fact that children with special needs had been “betrayed”. Schools were, in her view, exploiting children to benefit their own financial needs. Distinguishing between “good” and “bad” teachers, she wrote that the latter “gives up at the first setback” and is “positively encouraged by management to do so, for the sake of a cash injection, and so that her pupils need not be counted among those whose examination results will be made public”.

Warnock was made a DBE in 1984 and joined the Lords in February the next year, taking the title of Baroness Warnock of Weeke, in the City of Winchester. She remained in the Lords until June 2015.

She chaired the Committee of Inquiry into Human Fertilisation and Embryology, which looked at assisted fertilisation. The committee released the Warnock Report in 1984, recommending the establishment of a regulator, the Human Fertilisation and Embryo Authority (HFEA).

“Rarely can an individual have had so much influence on public policy,” said Dame Suzy Leather, chair of HFEA from 2002-06. “The committee she chaired clearly appreciated the fundamental moral and often religious questions raised by assisted reproductive technology, and yet it produced a coherent set of proposals for their regulation that has stood the test of time. The fact is that almost 20 years later we are still working to the rules suggested by Warnock.”

In 1986 she and her husband Geoffrey achieved an academic “double” when she became mistress of Girton College, Cambridge, while he was already master of Hertford College, Oxford, becoming the first couple to simultaneously head colleges at each of the two universities. Geoffrey Warnock retired from Hertford two years later and died in 1995. Warnock House at Oxford was named in their honour.

In 2010, Warnock was invited to contribute to the Commission on Assisted Dying, set up to consider if a change in law should be made. Two years earlier, Warnock had published the book Easeful Death, co-authored with Elisabeth MacDonald, which had explored the moral issues around the topic. Today, aiding or abetting suicide remains punishable by up to 14 years’ imprisonment under the 1961 Suicide Act. But a new bill, sponsored by Lord Falconer, had sought to change this and Warnock had encouraged its progress since its first tabling in the Lords in June 2014.

When Falconer’s Assisted Dying Bill was debated in the Commons during September 2015, Warnock – a secular churchgoer – was prompted to write the brief but poignant letter to The Observer: “It would surely be more honest if those who believe that their religion forbids assisting the terminally ill to die were simply to say so.”

Warnock was an outspoken commentator in other areas of public life. In 2014, for example, she said: “There is nothing easier or less significant than apologising to former colonies for, centuries ago, having colonised them. Nothing more futile than now expressing regret for our ancestors’ actions that were then regarded as normal, though would now be condemned.”

She also argued the Queen had been “right” to host a dinner attended by former IRA commander Martin McGuinness.

Her most recent book, Critical Reflections on Ownership, was published in August 2015. Here she examines the responsibility and love we have for things that are owned and goes on to investigate those things which we do not own, in particular the natural world.

Professor Karen Morrow of Swansea University, editor of the Critical Reflections series, told The Independent: “Mary Warnock’s philosophical thought has made its long made its impact felt in academia, but it has also proved hugely influential when applied to practical social and legal problems. It was therefore a delight when she agreed to write the first volume in the new series Critical Reflections on Human Rights and the Environment in which she turns her thought-provoking, clear-sighted and humane approach towards an important aspect of perhaps the most pressing issue of our time – the relationship between humanity and the environment.”

Dame Mary Warnock (Helen Mary Wilson), philosopher, born 14 April 1924, died 20 March 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments