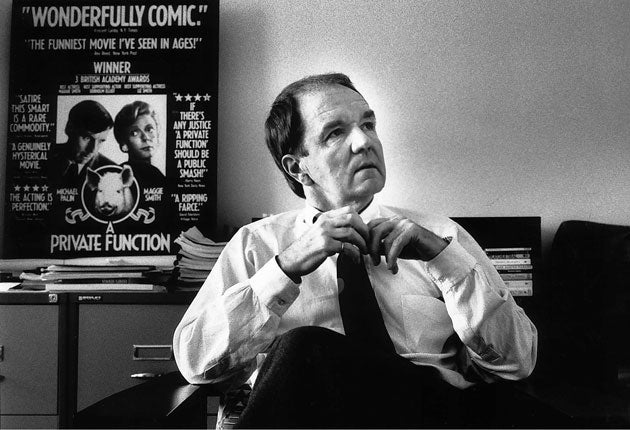

Mark Shivas: Film and television producer who worked with an unmatched range of writers and directors

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The producer Mark Shivas was a man of privacy but with a captivating gift for friendship. He was eventually to become Head of BBC Drama and then BBC Films, and his career in film and television illuminates 40 years of British culture.

He was born in Banstead, Surrey in 1938, his father an English master, his mother a librarian. Although not provincial, it was a background typical of many of those who succeeded in the expanding scene of the Fifties and Sixties. Shivas read law at Merton College, Oxford, but was soon drawn as a film journalist towards the world that excited him.

In a sense, indeed, his youthful, romantic view of Hollywood's great years inspired his entire career, and gave him a notion of standards and how things might happen, because when in 1964 he got documentary work for Granada Television, what did he find there – and what was the entire Golden Age of British television – but another version of the studio system? There were numerous companies, each with its own ethos. There were rivalries, and managements whose notions of profitability or taste had to be appeased, but there was also a wide (and government-regulated) desire to meet the middle of the market with professional integrity and taste, and there were long-standing alliances between people of like minds.

Good producers were somehow the lubricators of this system, and its flow of product, and when in 1969 Shivas became a BBC drama producer he was perceived by the management to be a safe and tactful pair of hands. His first show, The Six Wives of Henry VIII, broke ground in that it attempted serious drama within a mini-series format, but that idea was Gerald Savory's (the Head of Plays). Shivas himself was never in essence an innovator, a picker of new talent or an ideologue.

What he became was the conscience of the middle ground and the now-ignored idea that done properly drama can have wide appeal. The argument, of course, is in the word "properly". Again, most leading producers have a particular imprint but Shivas, who originated some shows and was assigned others, was diverse.

Consider this incomplete list of writers he worked with: Hugh Whitemore, John Hopkins, Dennis Potter, Alan Plater, David Hare, Christopher Hampton, Julian Mitchell, Henry Livings, Howard Brenton, Kingsley Amis, Jack Rosenthal, Frederic Raphael, Brian Clarke, Ian Curteis, Alun Owen, Tom Stoppard, William Humble, Alan Bennett, Peter Ransley, Anthony Minghella, Alan Scott, John Prebble, Roddy Doyle. And this of directors: Alan Parker, Michael Apted, Alan Clarke, Christopher Morahan, Clive Donner, Mike Newell, Jerzy Skolimowski, Nicholas Roeg, Gillies MacKinnon, Jack Clayton, Stephen Frears, Anthony Harvey.

Shivas could serve such a spectrum, from the wry Manchester grit of Rosenthal's The Evacuees (1975) to the philosophical whimsy of Stoppard's "Play of the Week" Professional Foul (1977) because his instinct was to judge the people first, which is why he could trust them and leave them to get on with it.

No other British producer can match this array, yet where his personal taste lay is unclear, and he probably felt that it was not his job to deploy it. I suspect he had soft spots for the middle-class TV storylines spun by his friends Frederic Raphael, Brian Clarke and Julian Mitchell, and for the Clive Donner-directed adaptation of Rogue Male (1976) and Alan Bennett's A Private Function (1984).

In life he drove a Morgan for a long time, and liked comfy restaurants, hotels of faded glamour, his Gloucestershire cottage and long domestic chats with friends like Visconti's collaborator Suso Cecci d'Amico. When with him one often felt that he was somehow an amused spectator of events in which he was actually the main player, and as television changed this is more or less what he became.

In the Eighties he went freelance and produced feature films: Moonlighting (1982), A Private Function, The Witches (1990), Mike Newell's marvellous Bad Blood (1981). In 1988 he became Head of BBC Drama, a studio mogul at last, and in 1993 Head of BBC Films. He green-lit many gems, from Minghella's Truly Madly Deeply (1990) to Roddy Doyle's The Snapper (1993), directed by Stephen Frears.

He had won three Emmys, five Baftas and a Prix Italia but the world was dumbing down around him. Later he kept going as an independent and had success with Alan Bennett, producing the Talking Heads 2 television monologues in 1998. But his predicament was that of an entire generation of producers created by the writer-led Golden Age system. The companies provided the cash and the producers parlayed the talent; dealings with banks and distributors were beyond them. Today, producers must kowtow to centralised organisations who only play safe. What modern producers need, Shivas realised, was business abilities themselves or at least a good business partner. In his last years he found one in Stewart MacKinnon, and they were about to embark on exciting work.

Which is to say that although Shivas was the exemplar of an epic yesterday, he had great sharpness. We were friends for nearly 40 years but only worked together once, when I wrote "Lloyd George" for The Edwardians series broadcast in 1973. The other times we never got the show on, although we did have one off-screen triumph. We owned a book written by a person who lived in Italy and Mark was phoned by someone in Los Angeles who wanted to buy it. He realised that our rights had run out, used the fact that I was in Australia to delay, flew to Rome and renewed our option. Then he announced that we were ready to deal. It was the Hollywood Buy-out, and his chuckle was the point of it, really.

When he got cancer he told hardly anyone, refused treatment and worked on. He was a man of discretion – he also kept his love life private. He had grace, good manners, and a great sense of fun.

Keith Dewhurst

Mark Shivas, film and television producer: born Banstead, Surrey 24 April 1938; Assistant Editor, Movie Magazine 1962-64; director, producer and presenter, Granada Television 1964-68; drama producer, BBC TV 1969-79, Head of Drama 1988-93, Head of Films 1993-97; Creative Director, Southern Pictures 1979-81; died London 11 October 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments