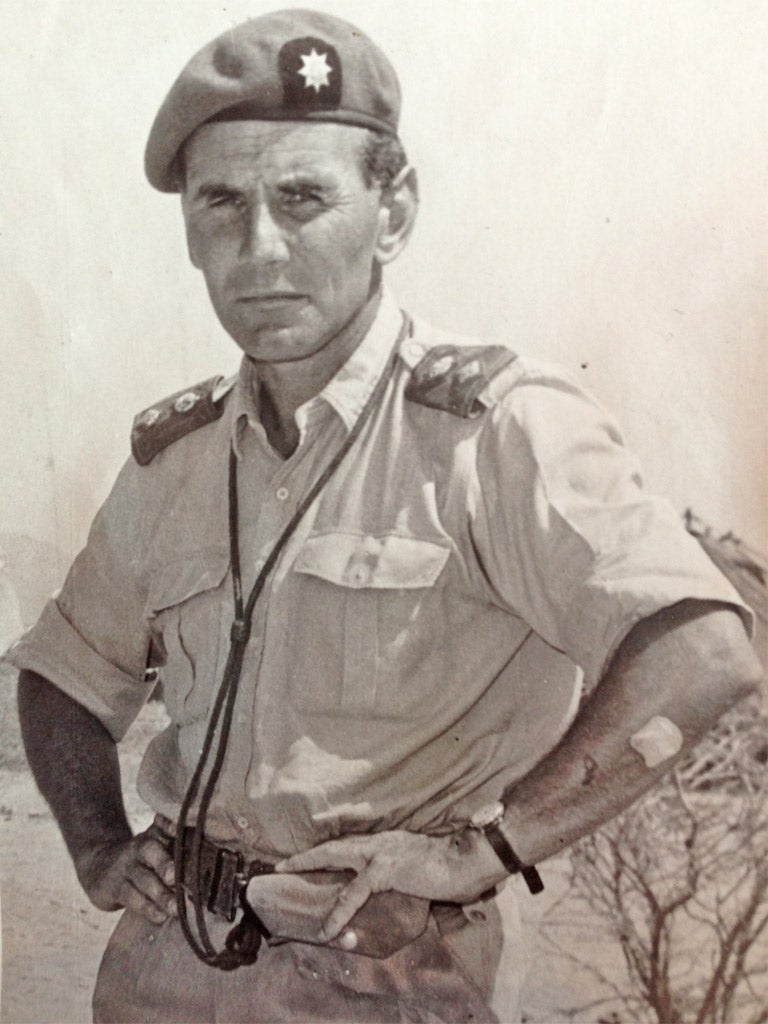

Major-General Jack Dye: Soldier who fought on the Rhine and went on to serve in Aden

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 1 March 1945, the task facing 25-year-old Acting Major Jack Dye as the Allies advanced through north-west Europe was to penetrate a walled-in country mansion bristling with hidden enemy troops. There had been moments for only the quickest of briefings. The Germans' whereabouts in the broad forested grounds, the outbuildings and the house itself were unknown, but Dye and his C Company had to push a way through for the 1st Battalion, the Royal Norfolk Regiment on the way to the Rhine.

The pincer movement of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery's 21 Army Group, including, as one half, the First Canadian Army, to which the Norfolks were attached, was meeting stiff resistance at this place, Kapellen, and much now depended on what the young British officer could achieve.

It would be two days before the Canadian General HDG Crerar's forward push resumed and the pincers met at Geldern in Germany on 3 March – the same two days in which Dye, accurately marking his route, led his men unhurt through multiple attacks, braved artillery fire, drove off an ambush on one of his platoons, took several prisoners and set up a forward outpost at the edge of woods on the mansion's far side.

"So inspiring was his leadership that the morale of his tired men was kept at a very high level and further efforts by the Bosche [sic] to dislodge him were repelled with great determination," the recommendation for his immediate Military Cross, signed by Monty, says. "Throughout the period of three days and nights with scarcely any sleep this officer showed a standard... which infected his whole company and without which a very difficult operation could not have been so successfully accomplished."

As Dye at last rested his head and slept, German resistance collapsed, the Canadians wiped out the last German bridgehead opposite Wesel, and the Rhine was won.

The genial, two-years-married soldier with dashing good looks and, by the account of more than one acquaintance, "a lovely smile", had joined up on an emergency commission with six months' training at an Officer Cadet Training Unit, and been gazetted as a 2nd Lieutenant. "He got on really well with his men – he loved people. He wasn't a martinet," a colleague from the Norfolks' successor Royal Anglian Regiment remembered.

But his origins remain deliberately obscure. This very private man left a letter with his regimental historian declaring he would not divulge details of his early life. The regiment has no record of his birthplace or school. After the Second World War Dye progressed up the ranks and in 1956 led a company of the 1st Battalion the Royal Norfolks in Cyprus in the campaign against General George Grivas and Eoka, the Greek Cypriot nationalist organisation. The Norfolks arrived at Nicosia in November 1955 and moved to Limassol in June the following year.

Dye was selected to attend staff college, and, by 1963 was Lieutenant-Colonel of the 1st East Anglian Regiment (Royal Norfolks & Suffolks), his old battalion and the 1st of the old Suffolk Regiment combined. He also attended the Imperial Defence College, now the Royal College of Defence Studies, in Belgrave Square, London.

In 1963 he went out to the former Crown Colony of Aden, given self-government as the State of Aden within a Federation just formed with the Aden Protectorates, to prepare for his men to be deployed there. This was "not technically active service, but things may be a bit warm", he told the BBC in an interview on the eve of the East Anglians' departure in February 1964.

Indeed, things were: on this, the British Army's last colonial counter-insurgency campaign, they would have to brave incidents of grenades, road mines, sniping, rocket-launchers and mortar-fire that multiplied tenfold from 286 in 1965, to 2,900 in 1967, the year the British withdrew. The East Anglians took part in the successful Radfan campaign against insurgents in May and June 1964, and while still in Aden were further amalgamated, merging in September 1964 with the 2nd East Anglian Regiment and becoming the Royal Anglian Regiment. Dye was appointed OBE in the New Year Honours of 1965.

But Dye's thorniest challenge was to lead the Aden Protectorate Levies – 15,000 Arab troops raised and commanded by British officers now brought together as the army of the new Federation of South Arabia. Doubts hung over these men's loyalty, and it fell to Dye in 1966 to become their first, and last, commander. The following June he had a mutiny on his hands, as much of Aden including its armed police joined in revolt on hearing the claim of the Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, that Britain had helped Israel win the June 1967 Six-Day War.

Dye nevertheless defended the South Arabian Army, writing to the author Major Frank Edwards in May 1969: "Through certain senior officers I was able to conduct negotiations with the Nationalist leaders.. and as a result the transference of power ... went very smoothly and without bloodshed."

On his return home in 1968 Dye was made CBE, becoming GOC Eastern District until 1971, and serving as Colonel Commandant the Queen's Division until 1974. He was the Royal Anglian Regiment's Deputy Colonel until 1976, and its Colonel from 1976-82. From 1983 until 1994 he was Vice-Lord Lieutenant of Suffolk, and from 1975 for the rest of his life a very active governor of Framlingham College, near Ipswich.

Universally known as "General Jack", and fit and upright into his nineties, he enthusiastically raised funds for soldiers' charities. He attended a Royal Anglian regimental function only days before he died, and this year's Radfan Dinner in June, which he would have hosted, was the first he had missed. His wife of 71 years, Jean, and his daughters, Julia and Jacqueline, survive him.

Major-General Jack Bertie Dye, soldier: born 13 December 1919; MC 1945; OBE 1965; CBE 1968; married 1942 Jean (two daughters); died Helmingham, Suffolk 10 June 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments