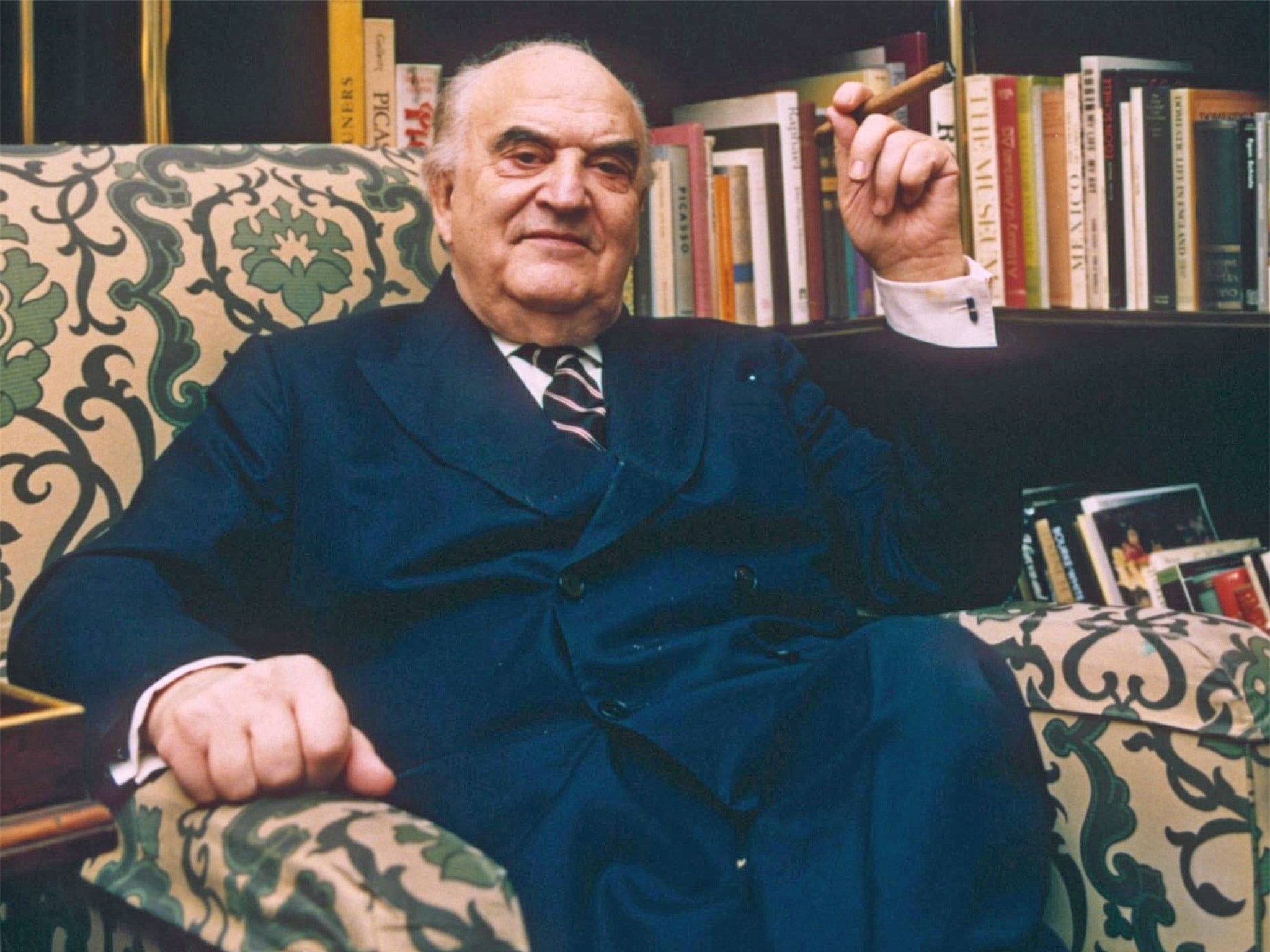

Lord Weidenfeld: Colourful and charming refugee from Nazism who co-founded one of the great publishing houses

Weidenfeld was part rogue, part Gatsby, part social dandy and snob, but a man of much humour and diplomatic skills

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.George Weidenfeld was for many years one of the most colourful, contradictory and ubiquitous personalities on the publishing scene, the source of much gossip, ribaldry, envy and attention among other members of the book trade, and a larger than life and very visible member of the social scene.

As with many other leading post-war publishers, such as Andre Deutsch, Tom Maschler, Paul Elek, Robert Maxwell and Max Reinhardt, he came to Britain as a refugee from Nazism and, polyglot and cosmopolitan, helped link British publishing to co-operative exchanges with Europe and America; but he spread his shadow over a much larger arena, into politics and diplomacy, music and academia, and into the social world of the rich, the aristocratic and the establishment's great and good.

It is impossible to describe Weidenfeld without warts because he was part rogue, part Gatsby, part social dandy and snob, but a man of great, if transparent, charm, of much humour and diplomatic skills, and he may have played an important if undisclosed part in Israeli international affairs. His ambition was great, but obvious, and if he was greedy it was more for recognition and honours than for wealth.

He was sometimes gullible and naive and a bad manager of money, which to him was a tool for social advancement. But he was a great promoter of deals, a persuasive compromiser and, once his position as a member of the establishment was secure, a promoter of causes and activities often of no benefit to himself. Weidenfeld always wanted to move among the great intellects of his time, and to be influential in public affairs and politics.

He was a schemer who sometimes overreached himself, but his powers of recovery were remarkable. He had few real enemies because he was good at winning round those who distrusted or were afraid of him, and he knew how to flatter and make feel important those he considered worth the effort.

He was born in Vienna, the son of a successful printer. Because of Nazi anti-Semitism, he spent a period at a Jesuit school in Verona. He also studied law, but without qualifying. Coming with his family to Britain shortly before the war, he worked from 1939 to 1942 for the BBC monitoring service, listening in to German broadcasts, and then became a news commentator on European affairs, later moving to the European and North American news service.

In 1943 he wrote and published The Goebbels Experiment. At the same time he became a regular contributor to the News Chronicle and began his long association with the Zionist cause, which led to his spending a year in 1948 as political advisor and Chief of Cabinet to President Weizmann, and during this period of change and turmoil in Palestine, now becoming the new state of Israel, he undoubtedly used his diplomatic talents to its advantage.

Through his wartime contacts, and those he made socially in London, he met many people prominent in public life, business and the arts, including Sir Harold Nicolson, whose son Nigel he eventually interested in joining him in starting a publishing house, Weidenfeld and Nicolson. He had already started Contact Publications, which mainly put out cheap editions of popular classics which were sold in the Marks and Spencer shops. When I first met him, in 1950, he told me that he was making, an "Edwardian-Victorian marriage", and shortly after he married Jane Sieff, daughter of Marks and Spencer's managing director.

Thereafter he concentrated on building his new publishing company. His charm, linguistic abilities, regard for excellence in literature and the intellectual disciplines, combined with the establishment contacts of Nicolson, enabled him to develop a varied list with many important authors joining him or being commissioned to write on their own subjects. New authors were discovered by his editors who on the whole were not given commercial constraints and he recruited such well-connected figures to work for him as Sonia Brownell (who married George Orwell on his deathbed); she had been part of the team, with Cyril Connolly and Stephen Spender, that had published Horizon, the most prestigious literary magazine of the day, and later Antonia Fraser.

His editors and scouts discovered much new talent, including Bellow, Böll and Borges, and commissioned books on historical, cultural and literary subjects. Weidenfeld's speciality was commissioning autobiographies. He had a bestseller in Nabokov's Lolita, a book I brought him when the author objected to me on political grounds after I had acquired rights, but its scandalous reception – in the days before the 1959 Obscene Publications Act introduced literary merit as a defence – was a principal factor in the de-selection of Nicolson as Conservative MP for Bournemouth.

Weidenfeld believed in lavish entertaining as a means of attracting authors and building his influence, and his parties became famous, attracting much notice in the social columns. They usually included politicians, literary figures, diplomats and well-known faces from the arts and media. Harold Wilson was a frequent guest, which led to Weidenfeld's knighthood in 1969 and his later elevation to the peerage.

This received much comment, most of it adverse, not least from senior publishing figures who felt their own claims might have been greater. He had recently published Wilson's memoirs, a book considered dull and revealing little of real import, which had sold badly; Weidenfeld had paid him a large advance.

His first marriage produced a daughter, his only child, who married a distinguished educator, Dr CA Barrett. The marriage was short, and he then married Barbara Skelton Connolly, ex-wife of Cyril, in 1956, who on the dissolution of their relationship remarried her first husband. In both divorce cases the other man was named as the co-respondent. Weidenfeld was always very fond of ladies, and although he was stout and had no conventional good looks, he had a legendary reputation as a lover. His corpulence was almost certainly due to his Viennese love of cream cakes and pastries. Although he enjoyed food, he seldom touched wine or spirits.

He had two further marriages, first to an American lady of considerable means, Sandra Payson Meyer, who became the first Lady Weidenfeld, from 1966-76, and finally to Anabelle Whitestone, who had been the companion of Artur Rubinstein, the eminent Polish-American pianist, and had inherited his important art collection. Weidenfeld was a collector, principally of Italian mannerist paintings, which gave a sumptuous appearance to his London residences, first at Eaton Square, then on the Chelsea Embankment. All his homes were suitable for entertaining, both for large receptions or big dinner parties, his particular delight, and guests were frequently invited to write their autobiographies for him on these occasions.

It would require too much space to name the many committees on which he sat, but he was particularly pleased to be appointed to the Royal Opera House Trust and to the board of the English National Opera. He received many European awards and honours, particularly from Germany, Austria and France. He was a genuine lover of opera and the classical theatre and entertained in the Royal Box at Covent Garden, but tended to play down his knowledge as it was not very English to be seen as intellectual or erudite – and he wanted to be viewed as English, as well as a cosmopolite. Strangely, he took little or no interest in the political activities of the House of Lords and it is possible that he may have felt uncomfortable there.

Although Weidenfeld and Nicolson became one of the most distinguished of post-war publishing houses – much of the credit must go to those he employed to work there and to advise him – it was never financially successful: there were too many authors of high quality but slow sales, and titles important to scholars but not to the general public. New injections of capital were constantly needed and the Weidenfeld marriages were usually timely enough to help weather times of crisis.

In 1985, when looking for a source of new capital, he met Ann Getty, the wife of Gordon Getty, a reclusive composer, who had inherited one of the largest American fortunes from his oil-tycoon father when they were taking a cure at a California health spa. He told her he wanted to set up a publishing company in the US, but he could hardly admit that he was in no way able to match her investment if she could be persuaded to go into partnership with him.

The opportunity came through the difficulties of Grove Press, a New York literary house founded by Barney Rosset that had fallen on hard times. Rosset reluctantly agreed to sell, remaining in charge of the company, which he was given to believe was being taken over to enable him to carry on his good work with new capital. Weidenfeld America came into being to work with Grove, but with a more popular trade lost. The two companies received massive injections of Getty money, and Weidenfeld and Nicolson, much in need, benefited too.

Weidenfeld's personal expenses, which included his entertaining and travel, always on a grand scale, had done much to worsen his finances, and these expenses now increased as he thought up new ways to please or impress the Gettys. He mounted an international conference in Israel on "The Future of the Orchestra" at which Gordon Getty tried to interest performers in his compositions, and he rented Leeds Castle for a conference on translation.

During the first two years of the Getty-Weidenfeld publishing venture, he squired her to many international gatherings around the beau monde, receiving much international publicity, but when it transpired that over $30m had been lost in a very short time by the American companies, the Getty accountants moved in and Weidenfeld was quickly disassociated from them. Not long after he sold Weidenfeld and Nicolson, although remaining as chairman.

In the weekend before the news of the massive loss was announced, I met him at a performance of Götterdämmerung at the Metropolitan Opera. He was on his own, unusual for him, a little subdued, but gave no hint of the storm about to break, and discussed the performance intelligently. At our previous meeting, two years earlier, he had had all the details of the Getty fortune and revenue at his fingertips and spoke of them like a river in spate that could never dry up. But when the tide turned and he was frozen out, he took his setback like a stoic.

There were many likeable things about George Weidenfeld. Many saw him as a figure of fun, a buffoon figure in a Goldoni farce whose pretensions would bring about his undoing, but there was another side, that loved the culture he had known as a youth, that could be affable and generous – and he worked hard to be liked and make friends, as well as to impress. He was witty, a good conversationalist and worldly-wise, but he could also be naive, especially in his chosen profession.

He stopped me once at the Frankfurt Book fair to boast, having sworn me to secrecy, of his great "coup", 'a joint history of the US and France by André Maurois (a devout Catholic novelist and biographer) and Louis Aragon (a Communist poet), for which he had just bought British rights for a large sum. When I told him that I would expect the sales in English to be modest, however well the book was received in France (where it did badly), his chin fell six inches; bedazzled by two big French names, he had given no thought to probable British indifference nor to the oddness of the project.

He recently launched the Weidenfeld Safe Havens Fund to rescue Christians from the depredations of Isis. "I had a debt to repay," he said. "It applies to so many of the young people who were on the Kindertransports. It was Quakers and other Christian denominations who brought those children to England."

Lord Weidenfeld was a "card" with all the period flavour that word implies, having something of Metternich and Disraeli in his character; his ambitions were for social acceptance and success, only marginally to do with public or financial matters. Like Falstaff, whom in appearance and manner he also resembled, he could laugh at himself, an ability that covers up many blemishes.

Arthur George Weidenfeld, publisher: born Vienna 13 September 1919; Kt 1969; cr. 1976 Life Peer, of Chelsea; GBE 2011; married 1952 Jane Sieff (marriage dissolved; one daughter), 1956 Barbara Connolly (divorced 1961, died 1996), 1966 Sandra Payson Meyer (divorced 1976), 1992 Annabelle Whitestone; died 20 January 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments