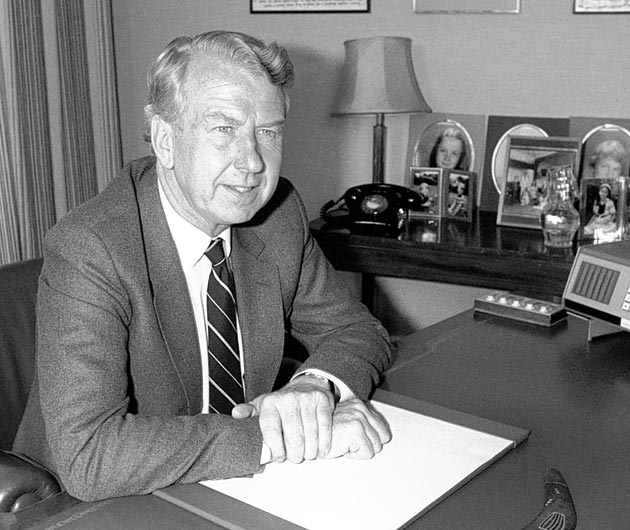

Lord Walker: Durable left-of-centre Conservative politician who served in government under Heath and Thatcher

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Peter Walker was one of the great survivors of the Conservative Party, spanning the Heath and Thatcher eras. At the time of his voluntary retirement in 1990, a few months before Thatcher's downfall, no 20th century politician, apart from Churchill and Lloyd George, had served longer in Cabinets and Shadow Cabinets, and it was appropriate that he should call his memoirs Staying Power. Though he never held one of the "great" offices of state, the variety of posts that he did fill, and the timing of them, ensured that he made significant contributions to British public life, proving a minister of considerable executive efficiency. Political durability was not his only claim to fame. His earlier role as a successful city financier, particularly with Jim Slater, would alone have ensured him the attention of serious commentators.

Peter Walker made his political name as the organiser of Edward Heath's successful leadership campaign in July 1965, the first time that Alec Douglas-Home's electoral system had been employed, by ensuring that every Tory MP was approached by somebody they liked. On the eve of polling Walker promised Heath, after an operation conducted with ruthless efficiency, "I can tell you you are going to win and tomorrow morning I will give you the figures". In a contest that saw the two leading contenders separated by only 17 votes Walker's operational skill tipped the balance, arguably altering the course of post-war British history. Thereafter Walker had unprecedented access to Heath, as a fellow exemplar of the technocratic society.

Walker never bore the key of the innermost Thatcher counsels. However, as a One Nation "wet" he was useful, not only for political balance within the Cabinet (at least in the early part of Thatcher's 11-year premiership), but for his skills as a persuasive communicator. It was a mark of Walker's indispensability that he could get away with quips that saw lesser men despatched to the backbenches. After Michael Heseltine's dramatic resignation from Cabinet in January 1986 there was much discussion as to whether Thatcher was a "listening" Prime Minister. In his speeches at the time, Walker would often introduce the story of the Duke of Wellington's first Cabinet – "An extraordinary affair: I gave them their orders and they wanted to stay and discuss them." Then, when the laughter had subsided, Walker would add, "I'm so glad we don't have Prime Ministers like that today."

Peter Edward Walker was born in Harrow on 25 March 1932, the younger son of Sydney Walker, a capstan operator at HMV's Hayes factory, and his wife Rose. On the outbreak of war he was due to be evacuated to Canada with his elder brother, but at the last moment his parents could not face the separation. The ship on which the two boys would have sailed was torpedoed in the Atlantic.

Walker was the quintessential scholarship boy of talent and ambition, winning a place at Latymer Upper School, one of the best academic day schools in London. Here he met stockbroking parents of his friends, from whom he learned much about the workings of the Stock Exchange, which fired his already precocious entrepreneurial spirit. He was always seen with his copy of the Financial Times on the train to Hammersmith.

Walker was also politically active from an early age. An excess diet of Bernard Shaw from the mobile library at his old primary school confirmed his belief in the Conservative philosophy. After speaking at a Conservative Conference in Central Hall, Westminster in 1946 aged 14, he was invited to meet the Tory grandee Leo Amery. The library at 112 Eaton Square, where Amery had plotted the overthrow of the Lloyd George coalition in 1922, was a far cry from Walker's semi-detached home in Harrow, but for the schoolboy it was a glimpse of the promised land, and he built his future life around Amery's advice. Amery told him to become financially independent before entering the Commons, as this would save compromise if resignation became necessary; secondly, he should be well-read (particularly in Edmund Burke) and allow time for thinking. It was ironic that the great exemplar of the Imperial Tradition of British politics should have set on his path one of the foremost exponents of post-war meritocratic Conservatism.

In 1948 the Walker family moved to Gloucester. Keen to make his own way as soon as possible, Walker eschewed sixth form and university and began work with the General Accident Insurance Company. Soon he was selling more policies than anyone else in the Cheltenham and Gloucester branches. National Service in the Royal Army Educational Corps confirmed Walker in his belief that Britain was not developing its best talents. The post-war Tory reforms of Rab Butler and the principles behind the famous Industrial Charter seemed to him the best way forward.

After National Service, Walker's commercial career blossomed and, moving back to London when his father opened a grocer's shop in Brentford, he became a non-marine broker with Lloyd's, soon taking half the brokerage on a massive Lufthansa airline policy. On the back of this Walker started an insurance company aged 20, concentrating initially on police insurance, as police stations were open 24 hours a day. With Edward du Cann, a future ministerial colleague, he formed Britain's first post-war unit trust company and became a market leader in equity-linked life policies.

Shrewd involvement in major property companies laid the foundations of his fortune. A series of profiles of Britain's leading young business men in the London Evening News brought Walker in contact with Jim Slater, then at Leyland, and from this stemmed the famous Slater Walker partnership. Walker's investment association with Slater Walker was fortuitous in that his involvement coincided with the good years; by the time the business was wound up in 1975, Walker had moved on and was already on the political ladder. His 18 years in business had, as Amery advised, brought him financial independence.

Walker first stood for Parliament in the 1955 General Election as Conservative candidate for Dartford (where Margaret Thatcher had been candidate in 1950 and 1951). He did one of the important radio election broadcasts and was noticed by Iain Macleod as a coming figure. His subsequent Chairmanship of the Young Conservatives from 1958-1960 coincided with the peak of its post-war membership. He was a trans-atlanticist, much admiring John and Robert Kennedy, and worked on John Kennedy's Primary election campaign team in 1960.

At the 1959 General Election Walker had brought the Labour majority in Dartford down to 1,200, but his entry into the Commons came at a by-election in Worcester in 1961, for which he was chosen as Conservative candidate ahead of Francis Pym and William Rees-Mogg. The West Midlands constituency was on the edge of Joseph Chamberlain country, whom Walker admired for his ability to rethink issues. Like Stanley Baldwin, another Worcestershire influence, Walker was captivated by the Commons and spent hour after hour on its benches. Initially he campaigned against British membership of the Common Market, travelling on an extensive Commonwealth tour in the cause. As an ardent supporter of Worcester County Cricket club, he was flattered when in Australia a vote of thanks was proposed to him by the great Don Bradman.

The difficulties of the Macmillan Government were already apparent in Walker's early months at Westminster. In July 1962 Macmillan sacked his Chancellor, Selwyn Lloyd, and six other Cabinet Ministers in the Night of the Long Knives. Walker not only thought this was wrong, as he had admired Lloyd's attempts to curb wage inflation, but he was brave enough to say so in no uncertain terms.

This was to prove a turning point second only to the meeting with Leo Amery. Lloyd asked Walker to be his Parliamentary Private Secretary when he returned to the Cabinet as Lord Privy Seal the next year. Walker took charge of Lloyd's parliamentary speeches, a task Lloyd had never relished, and with such success that after his first appearance again at the despatch box Lloyd asked his PPS, "When do we make another speech?" Lloyd became a godfather to Walker's first son and the two remained close friends, Walker characteristically joining in the presentation to Lloyd on his retirement that bore the inscription, "To Selwyn Lloyd, from his Parliamentary Private Secretaries, to whom he owes so much."

Walker was now one of the rising stars. At Alec Douglas-Home's request he had managed the successful Devizes by-election campaign in 1964 for Charles Morrison. With Ian Gilmour and Morrison, Walker became one of the leading figures on the liberal Tory wing, known as the "Gayfere Street set" after their Westminster base. Walker was eventually to marry Tessa Pout, Gilmour's secretary.

Although the Conservatives lost office after the 1964 General Election, the spell in opposition proved Walker's making. He was the youngest member of the Opposition front bench team and worked closely with Heath on the 1965 Finance Bill, leading on capital gains. This laid the foundations for Heath's leadership bid that summer (10 years later Walker recommended Margaret Thatcher to Heath for the 1975 Finance Bill, with similar results). After Heath's election as Tory leader, Walker became the youngest member of the Shadow Cabinet. As Shadow Transport Minister, he led a high-profile campaign against Barbara Castle's Transport Bill, effectively delaying much contentious legislation, which was later shelved by Richard Marsh, Castle's successor.

Shortly before the General Election, Walker was made Shadow Minister of Housing and Local Government, a political hot potato in the wake of the Redcliffe-Maud report on local government. After Heath's unexpected victory at the General Election in June 1970 Walker was initially appointed Minister of Housing and Local Government as a prelude to office as the first Environment Secretary, one of the two "super-ministries" Heath created in Whitehall.

The re-organisation of local government proved one of the most controversial episodes in Walker's career, bringing him the obloquy of many traditional Conservatives. The old county councils were abolished and the implicit collectivism behind the centralised replacement bodies was much resented; simultaneously, there was anger over the loss of those signposts of Middle England, such as Rutland. Walker later admitted that the changes remained a millstone round his neck. While at Environment, Walker pioneered a series of studies into inner-city problems, and though he was moved to the Department of Trade and Industry before he had time to implement important recommendations, the Labour Government's subsequent Cabinet Committee on inner-city problems was a legacy of the Walker initiative.

In 1972 Heath decided to move Walker to the second of his new "super" departments, Trade and Industry, after the conspicuous failure of the erstwhile businessman John Davies to adapt to the Westminster jungle. Heath knew that with Walker he would have a minister who would not neglect the House of Commons and the Party Conference activists. Walker brought in high-profile advisers such as Gordon Richardson, later Governor of the Bank of England, and assembled a first-rate team of ministers, including Geoffrey Howe, Michael Heseltine and Christopher Chataway. Important decisions were taken on exports, the Channel Tunnel and the motor industry. Peter Walker was firmly established as an interventionist minister, a free spender from the public purse. He proved a central figure in the energy crisis of 1973/74 that marked the end of the Heath Government, having talks with Sheikh Yamani and Arab oil suppliers in Switzerland on contingency plans.

On 19 November 1973 Walker announced a 10 per cent cut in petrol supplies and shortly afterwards, conscious of the Christmas post, arranged for the issue of petrol coupons, a move that brought home to the public the knife-edge situation. The energy crisis caused a strain in Walker's relationship with Heath, especially over the creation of an Energy Ministry, headed by Lord Carrington. For the first time in his career Walker was close to resignation. In the wake of the three-day week, Walker was an advocate of an early election and felt that Heath missed the electoral tide by delaying the contest till 28 February. The subsequent loss of office marked the beginning of the end of Heath's leadership. Walker was not in charge of Heath's campaign in February 1975, and in a contest that bore many resemblances to that a decade earlier, the organisational skills of Edward du Cann and Airey Neave helped Margaret Thatcher to the Conservative leadership.

Walker was sacked from the Shadow Cabinet by Thatcher and some thought this marked the end of his period in front-line politics. But they were mistaken. Walker was an important influence in persuading liberal Tories not to join the newly formed SDP. Willie Whitelaw brought about a rapprochement between Thatcher and Walker, who was appointed Agriculture Minister when the Conservatives returned to power in May 1979, on the Lyndon Baines Johnson principle that it was better to have a licensed dissenter inside the tent rather than outside. Walker thus began a continuous spell of 11 years in the Cabinet. At Agriculture he was assiduous in his pursuit of British interests, "saving" the Cox's Orange pippin, marketing Lymeswold cheese and negotiating a European fishing agreement. With his own earlier farming interests at Martin Court, Droitwich, he had practical experience of the issues of the day.

In 1983, with impending trouble in the coal industry, Thatcher made Walker Secretary of State for Energy. Though Walker did not get on particularly well with Ian MacGregor, Chairman of the Coal Board, he proved more than a match for Arthur Scargill. He also reined in some of the atavistic Tory attitudes, advising Thatcher not to start civil proceedings against the mining unions. He maintained private links with Norman Willis, TUC General Secretary. The privatisation programme, notably British Gas, with its "Tell Sid" campaign, was the underlying theme of his later years in the department.

After the 1987 election victory, Thatcher kept Walker on board again, appointing him Welsh Secretary, though some political wags said that he got this portfolio because the Prime Minister thought his constituency, Worcester, was in the Principality. His time in Wales proved the most notable example of his executive skills. He easily won important financial battles with John Major, the new Chief Secretary to the Treasury. He ran the Welsh Office in a pragmatic left-of-centre manner that won plaudits even from his political opponents, reducing unemployment from 13 per cent to six per cent, the biggest drop in the United Kingdom. He pioneered a Valleys initiative, attracted major investment from Bosch and Toyota, and gave the go-ahead for the second Severn Bridge.

He stepped down of his own accord at Easter 1990, thus missing the Cabinet dramas later that year when Thatcher was toppled, though he warned Michael Heseltine, whom he supported for the leadership, to double-check every pledge. He was never a serious candidate for the leadership himself.

Although, in the time-honoured phrase, Walker did now "spend more time with his family", he was always a pro-active figure and he took up the threads of his business career. He had a wide-ranging portfolio of important directorships, including Rothschilds, Tate and Lyle, Dalgety and, to some raised eyebrows, British Gas. He was Chairman of Thornton and Co, and from 1999 Vice Chairman of Kleinwort Benson. He published three books.

Despite his many achievements, there remained an element of unfulfilled potential about Walker's political career, especially after his time as Welsh Secretary, which was widely seen as a paradigm of the kind of compassionate and efficient Premier he might have been, if the cards had fallen differently. But Walker's fate was to have been a Disraelian in a world of monetarists, one who believed, like his mentor Burke, that "parliament is a deliberative assembly of one nation, with one interest, that of the whole". This was for him a failure of political timing, not integrity.

D R Thorpe

Peter Edward Walker, businessman and politician: born Harrow 25 March 1932; Member, National Executive, Conservative Party 1956-70; National Chairman, Young Conservatives 1958-60; MP for Worcester 1961-1992; Minister, Housing and Local Government 1970; Secretary of State for Environment 1970-72, Trade and Industry 1972-74; Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries 1979-83; Secretary of State for Energy 1983-1987; Vice Chairman, Dresdner Kleinwort 1999-; MBE 1960, cr. 1992 Life Peer, Baron Walker of Worcester; married 1969 Tessa Pout (three sons, two daughters); died 23 June 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments