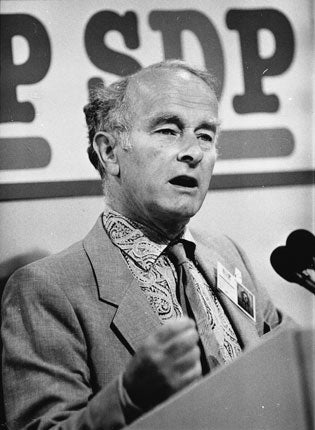

Lord Kennet: Writer and Labour politician who defected to help form the SDP then later returned

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Wayland Kennet was a writer and Parliamentarian of heavyweight intellect and independence. He was welcomed back to the Labour Party, his original political home, in 1990 after the demise of the Social Democratic Party. He had been as important a figure as any, outside the "Gang of Four" of Roy Jenkins, William Rodgers, Shirley Williams and David Owen, in forming the new breakaway party in 1981.

He was born Wayland Young in 1923, son of the first Lord Kennet, a First World War hero and one of Stanley Baldwin's ministers, and the sculptor Kathleen Bruce, widow of Scott of the Antarctic. Wayland was sent to Stowe School, still under the direction of its founding headmaster, J.F. Roxburgh. It is not surprising that a combination of his mother's genes and the monuments of the unique park at Stowe, the work successively of Charles Bridgeman, William Kent and Capability Brown, nurtured his lifelong love of architecture and the "built environment" – a phrase which I believe Wayland Kennet coined.

Trinity College, Cambridge, was a seminal influence, though his architecture studies were interrupted by the Second World War, and equally seminal was his service in the Navy in 1942-45. He was ever serious about Defence matters and I have never heard anyone administer such stinging rebukes as his to parliamentary colleagues for being cavalier in their policies about servicemen's lives during a Forces visit to the Far East in 1965. If one's country asked young men to fight, then it was up to that country to provide nothing but the best in terms of quality equipment. If a country thought it could not afford the best equipment, then it should rethink its military commitment and role.

In 1948, Young married Elizabeth, daughter of Captain Bryan Adams DSO RN, who was to be his partner in every sense and a woman with a prolific literary output, taken seriously in her own right as a Defence and environmental expert and scholar.

Two short spells in the Foreign Office, in 1946-47 and 1949-51, made it clear to Young that he was more suited to an "own-man" life, in journalism and authorship, rather than team membership. And, truth to tell, perhaps the Foreign Office found him prickly and difficult in the same way as political colleagues were to do decades later, not least those who admired his intellect, integrity and energy.

The book that made Young's name was his 1949 study The Italian Left. Years later, when I told Altiero Spinelli, the European Commissioner and Communist MEP, that Young, by then Lord Kennet, was coming to join the European Parliament, he said, "Oh, yes, Nenni, Saragat, Taligatti and I all agreed that Young's was the most perceptive study of the Left in Italy in English – or any other language." This was high praise indeed.

The twin interests of architecture and armaments dominated his writing. With his wife, in 1956 he published Old London Churches. Most of his writings related to the East-West conflict, and my own first memories of the Kennets are of going to their hospitable home (J.M. Barrie's former London house, on the Bayswater Road), where Wayland and Elizabeth played hosts to many a seminar on the subject, leading to the production of a Fabian Society or other political pamphlet.

When Labour came into office in October 1964 – four years after Young had succeeded his father as Lord Kennet – Harold Wilson, having had a lot to say about the 14th Earl of Home, was wary of appointing hereditary peers to his administration. Kennet joined the Government in less than auspicious circumstances. Richard Crossman's diary entry for 4 August 1966 encapsulates the position, as Kennet entered the Ministry of Housing and Local Government: "I went back to my table and resumed my conversation. Soon the doorman was back: 'He's on again.' I went back to the phone. Harold's voice: 'I'd forgotten to tell you I want you to have Kennet as well.' 'Kennet!' I said. 'But what for?' "Instead of Dick Mitchison.' 'But Dick Mitchison,' I said, 'is absolutely first-rate.' A rather dry voice replied, 'He's over 68, we want young blood. You must trade him in.' I said, 'Thank you very much.' And that was that."

Kennet devoted himself to constructive ministerial grind, in particular the Town and Country Planning Act, especially the sections dealing with historic buildings and the centres of historic cities. Perhaps his most valuable work was as Chairman of the Preservation Policy Group, from whose thinking came the legislation on controlling works to listed buildings by putting a blanket building preservation order on all buildings of architectural or historical interest, and the clause deterring owners of listed buildings from allowing them to fall into disrepair. Kennet-inspired studies of Chichester, York and other medieval cities brought credit to the Ministry of Housing. Dame Evelyn Sharpe, the formidable Permanent Secretary at the Ministry, told me she liked working with Kennet, because he showed such a fertile mind in teasing out solutions to problems. And the problems on which Kennet worked in the 1970s were of an importance which went some way to compensating for the fact that he was not included in the 1974-79 Labour government, although he was appointed a Foreign Affairs spokes-man in the Lords.

From 1970 to 1974, Kennet was the Chairman of the Advisory Committee on Oil Pollution of the Sea, which in the aftermath of the Torrey Canyon disaster of 1967 was a topical issue. Later, he was an active member of the Cathedrals Advisory Committee and Redundant Churches Fund.

In 1975, Kennet visited China, where the universities had re-opened after the Cultural Revolution. This is how he described his experience to his colleagues in Strasbourg, in a typically thoughtful passage: "The Cultural Revolution had settled the great question: who selects undergraduate students? The question was answered: their workmates in the fields and factories where they have been between school and the university... From this fact we may be sure that there will be rapid technological advance in that country with the generation of students who are just now emerging into the national economy."

During his brief membership of the Labour Delegation to the indirectly elected European Parliament, in 1978-79, Kennet spoke for the Socialist Group on Foreign Affairs and Pollution, and tried to spur Europe into following Britain in enforcing new international conventions on insurance liability and the Law of the Sea.

Kennet, living in London, faced an educational problem, which Labour MPs, with families growing up in their constituencies do not face in such acute form; the difficulty was described by Crossman in his entry for 18 May 1968: "This evening Wayland, Elizabeth, Anne and I all had a terrible argument about children's schooling. They had sent their children to primary and comprehensive schools in London but now they're sick of it because the children don't do well. They've taken the boy out and sent him to a fee-paying school where he's learning Latin at the age of 10. One of their girls was taken out and sent to a grammar school where she could try for Cambridge. They have much more experience with comprehensive schools than us because their children are older and I'm sure we shall find many of the same difficulties. But I couldn't help saying that Labour ministers have a special responsibility. Wayland disagreed and suddenly we were in the eternal argument about what we socialists should do with our children. They took the broad Balogh view that the children come first and one must find out what is best for them and do it. I said, 'That may be true of other people, but, if you're a Labour minister you can't, or you shouldn't.' Then, because I hate sounding self-righteous, I got bad-tempered and we had a filthy row that got worse when it spread over on to Vietnam."

It was perhaps the schooling dilemma which sowed the seeds of Kennet's disenchantment with the Labour Party which, a decade later, led to the creation of the SDP.

Kennet entertained a high esteem for the writings of Arthur Koestler. In 1963 Koestler edited a collection of essays entitled Suicide of a Nation?, in which John Cole, Cyril Connolly, Henry Fairlie, John Grigg, Hugh Seton-Watson and Lady Kennet (Elizabeth Young) described the signs they perceived of Britain's accelerating decline. It influenced Kennet powerfully, and prompted Kennet to direct his considerable energies to spatchcocking together a collection of essays under the title The Rebirth of Britain (1982).

As a former Labour colleague, who was deeply angry with Kennet for having been one of the half-dozen prime movers in forming the SDP, who split the Labour Party and so consigned the Left to Opposition for a generation, I have to confess it was a formidable contribution, and possibly the most seriously pored-over book of the mid-1980s. In his introduction Kennet wrote: "This is not a warning book: it's a 'let's get on with it' book."

Kennet made sure that the tone of the writing was gentle and concerned. He believed that those who had become social democrats were as weary of the stale messianics of both Margaret Thatcher and the then Labour Party as they were of their facile diagnoses and zany – a favourite Kennet word – remedies.

It was Kennet's bustling pressure that extracted thoughtful contributions from the late Peter Jenkins on "The Crumbling of the Old Order", David Marquand on "The Collapse of the Westminster Model", Shirley Williams ''On Modernising Britain", Bill Rodgers "On Industrial Partnership", Roger Morgan on "Breaking the Mould without Rocking the Boat" and David Owen on "The Enabling Society". The first essay, appropriately, was a regurgitation of Roy Jenkins's 1979 Dimbleby Lecture, which was the catalyst for the founding of the SDP. Christopher Brocklebank-Fowler, erstwhile Conservative MP for King's Lynn, reflected on "Joining the SDP from the Right", and Sue Slipman balanced that, as an ex-Communist, with "Joining the SDP from the Left". Arguably the two most profound essays were by James Meade, the Nobel Prize-winning Cambridge economist, on "Restoration of Full Employment", and Kennet's essay on "East-West Relations for a Medium Power".

For Kennet, the way that Communism was being forced on the Russian people constituted a great spiritual loss for the smaller peoples beside. Freedom to meet other peoples and to experience their language and culture was for many an inseparable part of liberty itself. From the bottom of his heart, Kennet put it: Why can we not come and go at our own sweet will in Russia, as freely as we can in one another's countries in the West? Why can we not behave naturally there? This is Europe, after all.

As his colleague in the European Parliament, I noticed that, along with Gwyneth Dunwoody, Mark Hughes and John Prescott, Kennet was one of the best among the British MEPs at making friends with colleagues of other nationalities. He had a healthy, intense curiosity about other people.

Perhaps Crossman captured the essence of Kennet when he wrote in May 1966: "My last meeting that day was a full-scale Ministry conference on historic buildings. Kennet is really splendidly energetic. Though he peeves me a little by his desire to take everything over, I am delighted that he is that sort of person."

Kennet's capacity to peeve other people – and it existed – was surpassed by his energy and capacity to identify worthwhile causes.

Tam Dalyell

Wayland Hilton Young, writer and politician: born 2 August 1923; succeeded 1960 as second Baron Kennet; Editor, Disarmament and Arms Control, 1962-65; Parliamentary Secretary, Ministry of Housing and Local Government 1966-70; Chairman, Advisory Committee on Oil Pollution of the Sea 1970-74; Chairman, Council for the Protection of Rural England 1971-72; Opposition Spokesman on Foreign Affairs and Science Policy, 1971-74; MEP, 1978-79; Chief Whip, Social Democratic Peers, 1981-83; SDP spokesman in House of Lords on Foreign Affairs and Defence 1981-90; Chairman, Architecture Club 1983-94; Vice-Chairman, Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology 1990-93; married 1948 Elizabeth Adams (one son, five daughters); died 7 May 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments