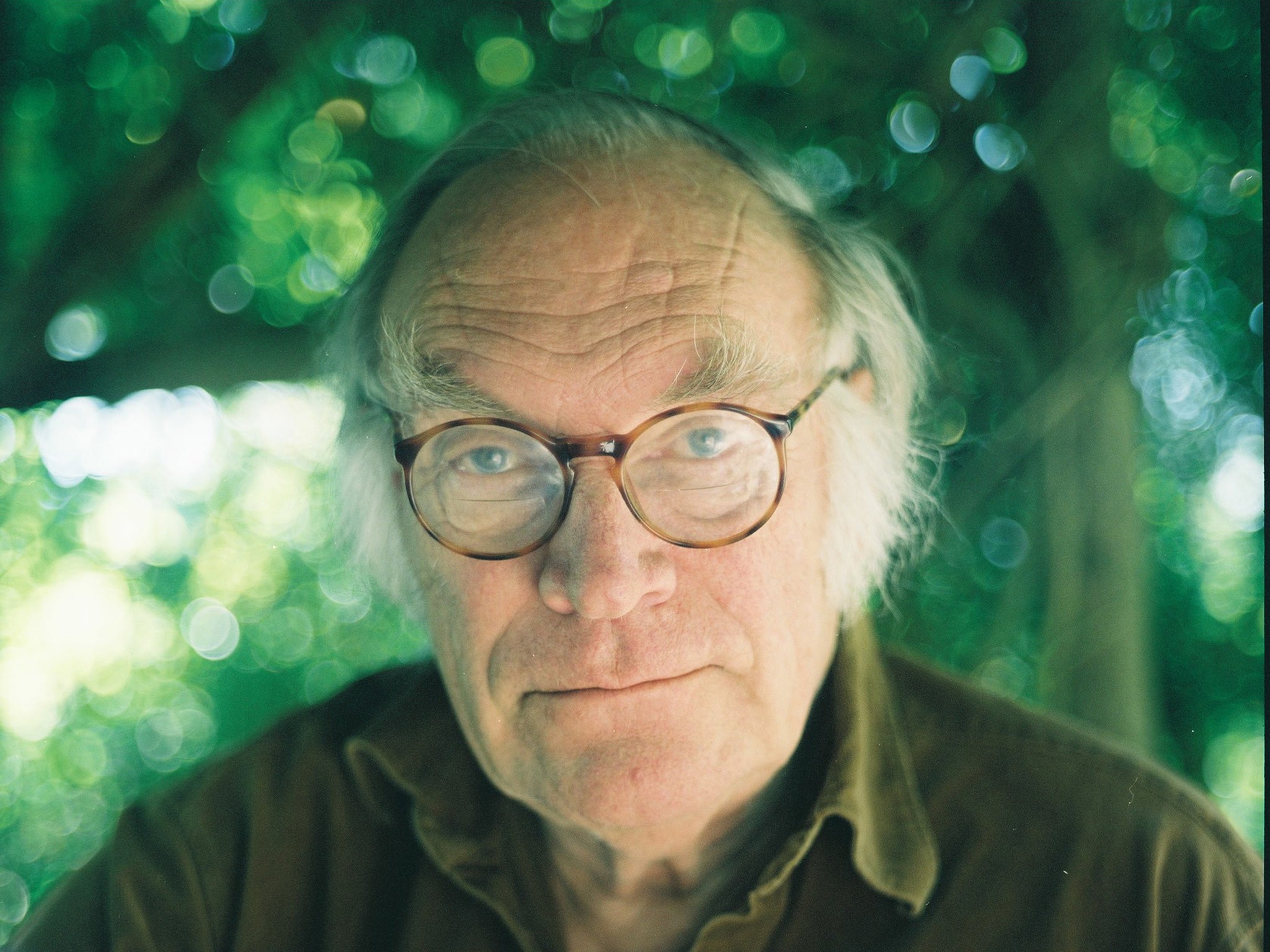

Lord Birkett: Director, producer and administrator who worked closely with Sir Peter Hall at the National Theatre

An intriguing, unconventional streak ran through Birkett's life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In tandem with the impeccable Establishment credentials and personal charm which made Michael Birkett a natural choice as Vice-President of the British Board of Film Classification or to oversee the protocol of royal galas during his time as the National Theatre’s Deputy Director under Peter Hall, there ran an intriguing, more unconventional streak.

In his earlier career in films, many of his choices both in the production office and behind the camera were far from the obviously commercial while much later, ensconced further along the river from the National Theatre, he was an energetic Director of Recreation and the Arts for the GLC at County Hall.

Son of the first Baron Birkett of Ulverton, the advocate who had been alternate judge to Justice Lawrence at the Nuremberg Trials, Birkett had a happy childhood and schooldays at Stowe where his artistic leanings were fostered. At Cambridge he was active in the Film Society, becoming a devotee of Soviet cinema, and even busier in undergraduate theatre during a golden period which nurtured talent including directors Peter Hall, John Barton, Peter Wood and Toby Robertson. A lifelong friendship developed with Hall, a subsequent colleague on films and at the National Theatre; Birkett had the rare 1950s student luxury of a car which took them off to Stratford and it was he who gave Hall his first glimpse of Glyndebourne.

Determined on a career in the arts – Birkett inherited no vast fortune and needed to work – he spent most of his early professional life in a then-flourishing British cinema. As one of Michael Balcon’s Ealing Studios trainees he began as third assistant director on The Ladykillers (1955), rising to second and then first assistant and gaining experience on films such as Dunkirk (1956), Seth Holt’s accomplished film noir Nowhere to Go (19580 and the exotic world of Island in the Sun (1957).

He enjoyed working on Jack Clayton’s exploration of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw in The Innocents (1961), deeply impressed by Clayton’s perfectionism and the deep-focus camerawork of Freddie Francis. As a producer he oversaw Clive Donner’s Some People (1962), a lively film shot in cinéma vérité style with Kenneth More surrounded by a cast of bright hopefuls including David Hemmings.

An admirer of Harold Pinter, Birkett as producer was crucial to setting up the film of The Caretaker (1962) in which Alan Bates and Donald Pleasence recreated their stage roles with Robert Shaw. Distributors dismissed the idea and without the chance of a commercial showing no money could be found; a group including Birkett, Pinter, Donner (who directed the tight, economic film) and Bates, all deferring payment, raised the funding, much of it in donations from figures such as Noel Coward (a Pinter fan), Elizabeth Taylor and Peter Sellers.

After directing, from a script which he co-authored, his film of Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale (1964) with the farouche Robert Helpmann ideally cast as The Devil, Birkett had a less than joyous time working as associate producer on the overblown misfire of Joseph Losey’s Modesty Blaise (1966), but then enjoyed one of his happiest periods, associated with Hall, who was running the fledgling RSC. He produced the 1968 film version of Hall’s much-revived A Midsummer Night’s Dream; some of the fairies, not entirely happily smeared in green body-paint, were heavily handled although Judi Dench’s Titania remains a delight.

He also supervised the filming of Peter Brook’s production of The Marat-Sade (1967) and his famously revisionist scrutiny of King Lear (1971) with Paul Scofield which divided opinion, and later, for TV, he produced one of Brook’s epic ventures which began at his Parisian Bouffes du Nord base, The Mahabharata.

When Hall succeeded Laurence Olivier as Director of the National Theatre he brought on board several figures from his Cambridge and Stratford pasts, including Birkett as, initially, Deputy Director. It was a good choice; the affable Birkett was popular with both actors and administrative staff.

There were some who regarded him as a Hall acolyte, but although he was a loyal friend he was perfectly capable of standing up to his boss. He proved both supportive and hard-working during the vexed and often-delayed move from the Old Vic during 1974-75 (he sighed wearily at one stage – “The chances of getting in or out of the South Bank advance and retreat like the waves of the sea”) and during the later winter of discontent which saw widespread press attacks and the whole operation bedevilled by sometimes ferocious industrial action.

Charged with organising royal galas to celebrate the eventual opening, Birkett had the task of trying to arrange the simultaneous visits of the Queen (to the Olivier) and her sister (to the Lyttelton) in 1976. Her Majesty’s entry into the Olivier auditorium was timed to a fanfare from Household Cavalry trumpeters which segued into a National Anthem unwisely re-arranged and played so staggeringly badly ( with many wrong notes like high-decibel farts) that Princess Margaret, progressing to the Lyttelton escorted by Birkett, stopped in frozen horror to demand “What the bloody hell is THAT??”

Later at the NT Birkett took an a new role as the organisation’s consultant on film deals and sponsorship before leaving in 1979 to join the GLC.There, too, he was popular and respected, heavily involved in events such as 1984’s Thames Day extravaganza, and a vital enabler of talent; director Yvonne Brewster, formerly an Arts Council officer, has stressed how much, in the dying days of the GLC, Birkett helped her find funding for a production of the Haiti-set play The Black Jacobins.

In later years Birkett remained active; between 1990-2008 he chaired the Donatella Flick Conducting Competition and in 2009 published a guide to Wagner’s Ring Cycle, The Story of the Ring. He remained deeply sceptical of a press which had been at times aggressively hostile during his time at the National; the only newspaper allowed in the Birkett household was The Independent, the cryptic crossword of which was almost invariably completed by mid-morning (the Sunday Times, which employed several friends, was occasionally permitted). The gift of friendship, too, remained lifelong; a host of others echoed Peter Hall’s description of him as “a hugely generous and enthusiastic spirit”.

Michael Birkett, producer, director and administrator: born 22 October 1929; married 1960 Junia Crawford (died 1973), 1978 Gloria Taylor (died 2001; one son); died 3 April 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments