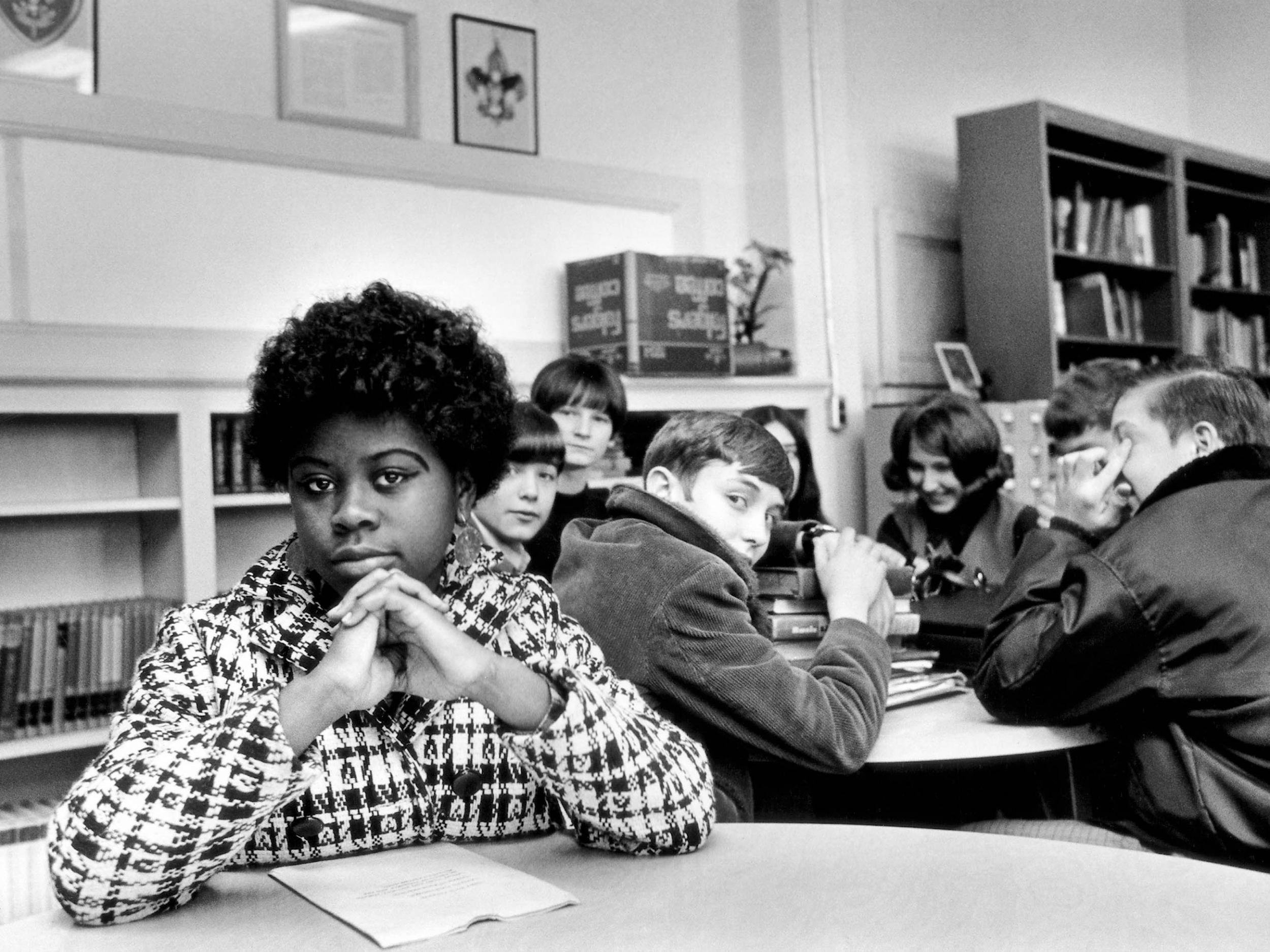

Linda Brown: American civil rights icon who helped end segregation in schools

When she was barred from attending an all-white elementary school, she became the centre of a landmark Supreme Court decision that kickstarted a global movement

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

All Linda Brown Thompson wanted was to go to Sumner Elementary School. But she was black and the institution in Topeka, Kansas, four blocks from her home, was segregated, open to only white students.

“I didn’t comprehend colour of skin,” she said later. “I only knew that I wanted to go to Sumner.”

Brown, a third-grader who simply wanted to avoid a long walk and bus ride and join her white friends in class, went on to become the symbolic centre of Brown v Board of Education, the transformational 1954 Supreme Court decision that bore her father’s name and helped overturn racial segregation in the United States.

One of the most famous Supreme Court cases in American history bore Brown Thompson’s last name almost by chance. Topeka, a city that was less than 10 per cent black at the time of the case, had integrated high schools and had begun integrating its middle schools. Her father – the Rev Oliver Brown, an assistant minister at St Mark’s African Methodist Episcopal Church – was just one of 13 plaintiffs who sought to ensure the city fully integrated the rest of its schools.

He was recruited by the NAACP (the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), which had organised four other class action lawsuits challenging high school segregation in South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware and the District of Columbia. According to the Brown Foundation, which promotes the history of the case, Oliver Brown was named the lead plaintiff “as a legal strategy to have a man at the head of the roster”.

Packaged together, the suits were successfully argued by an NAACP legal team led by Thurgood Marshall, who later served as a Supreme Court justice. The court unanimously ruled on 17 May 1954 that school segregation violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

I feel that after 30 years, looking back on Brown v the Board of Education, it has made an impact in all facets of life for minorities throughout the land

“Segregation of white and coloured children in public schools has a detrimental effect,” the court said in its ruling, which overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine that had stood since the 1896 case of Plessy v Ferguson. The decision paved the way for a gradual and sometimes violent integration of schools and other public facilities, although many schools in the south – and even in Brown Thompson’s home town – were not fully integrated for years.

“I feel that after 30 years, looking back on Brown v the Board of Education, it has made an impact in all facets of life for minorities throughout the land,” Brown said in a 1985 interview for Eyes on the Prize, a PBS documentary series on the civil rights movement. “I really think of it in terms of what it has done for our young people, in taking away that feeling of second-class citizenship.”

At the time of the decision, Brown Thompson said she was just happy she could legally attend Sumner – a school that still tried to bar her admission on the day the Supreme Court ruled in her favour. She later attended an integrated middle school, where she was sometimes hounded by journalists who tracked her grades (she reportedly never earned “less than a B” on her end of year report card), and an integrated high school in Springfield, Missouri.

It was only there, she told The New York Times as a senior in 1961, that she began to realise the significance of the court decision.

“Last year in American history class we were talking about segregation and the Supreme Court decisions,” she said, “and I thought, ‘Gee, some day I might be in history books!’”

Linda Carol Brown Thompson was born and raised in Topek. She said she grew up playing with children of all races and didn’t think twice about attending whites-only Sumner. The family received a registration form for the school in 1952, apparently by mistake. The school’s refusal to accept her led her father to meet with the NAACP.

He “felt that it was wrong for his child to have to go so far a distance to receive a quality education”, Brown said in Eyes on the Prize.

She moved to Springfield as a teenager and her father became pastor of a church in the city. Years later, she returned to Topeka and took on the civil rights mantle of her father, who died in 1961.

Brown Thompson was part of a group of Topeka parents who, in 1979, joined with the American Civil Liberties Union to successfully argue for the reopening of the Brown case. The parents argued that because of housing patterns in Topeka, racially segregated schools remained in the city, in violation of the 1954 ruling.

I didn’t comprehend the colour of skin. I only knew that I wanted to go to Sumner

“We feel disheartened that 40 years later we’re still talking about desegregation,” Brown Thompson told The Washington Post in 1994. “But the struggle has to continue.”

That same year, the district adopted a desegregation plan that closed eight elementary schools and opened several new elementary and magnet schools.

A marriage to Charles D Smith ended in divorce, and Brown later married Leonard Buckner. A complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

Brown Thompson worked as a teacher with the Head Start early childhood programme and was a programme associate at the Brown Foundation, according to the organisation’s website.

She sometimes said that she had little memory of the court case that changed her life, as well as the lives of millions of African Americans across the country. She told The Times in 1961 that she couldn’t remember if she went to court at any point during the case, and that even in Topeka her peers were incredulous that she had played a significant role in history.

When photographers swarmed her classroom after the decision, on the first day of school in September 1954, she said her classmates thought it “was very funny” they were taking pictures of her. In fact, she said, “they didn’t believe me”.

Linda Carol Brown Thompson, civil rights campaigner, born 20 February 1943, died 25 March 2018

© Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments