Lewis Morley: Photographer whose work captured the essence of the Swinging Sixties

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

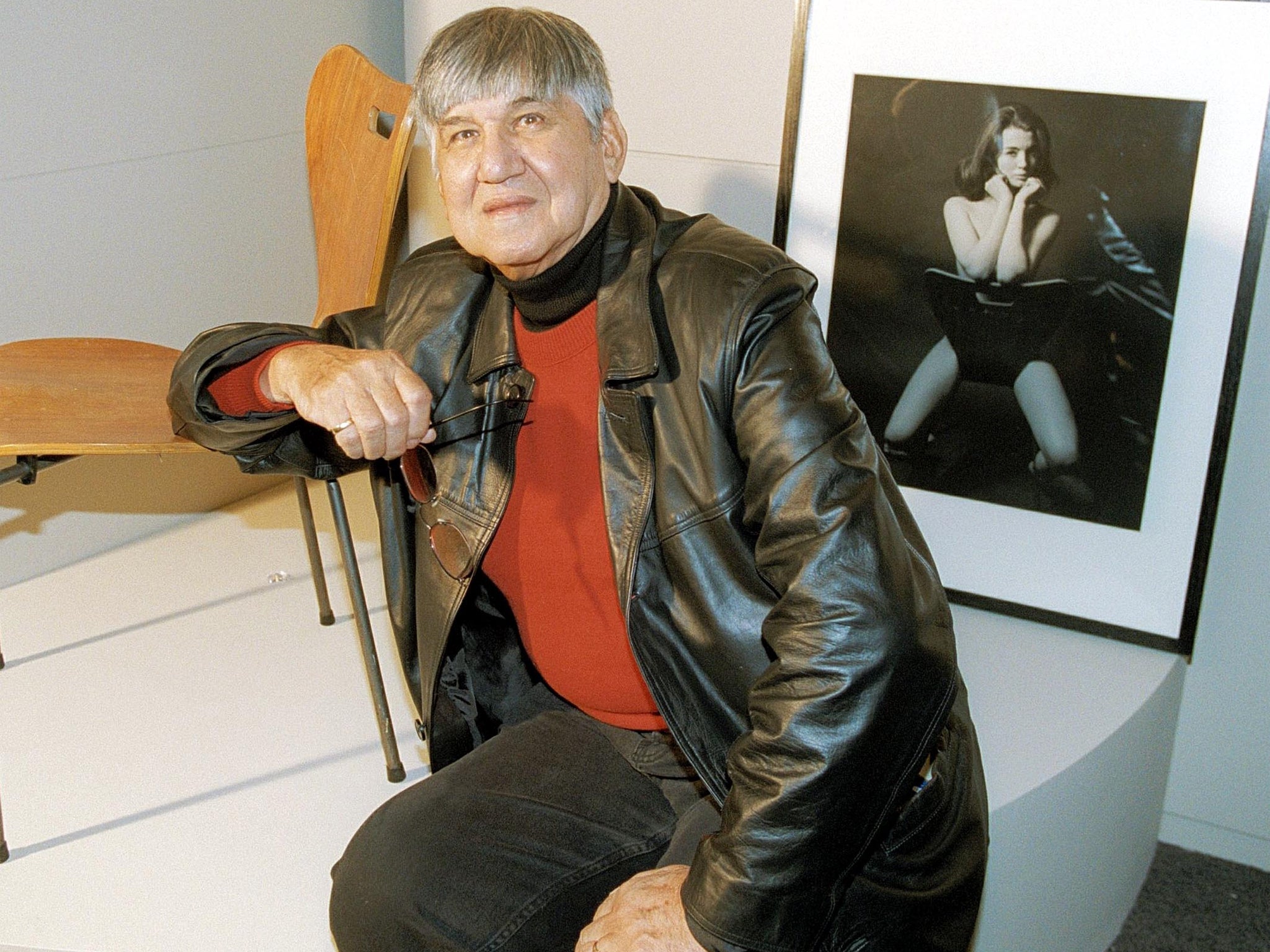

Your support makes all the difference.Lewis Morley was a photographer closer than most to London's swinging Sixties, capturing the flamboyant spirit of the times as he chronicled the new idols of British society, and he will always be internationally remembered for his defining image of Christine Keeler sitting naked astride a copy of an Arne Jacobsen chair. It became one of the most recognised and emulated images in photographic history.

Taken in May 1963, the photograph came to represent the sexual revolution that was erupting in Western countries – and the Profumo affair, which might have gone unnoticed had Keeler been solely involved with John Profumo, Secretary of State for War, or Yvegeny Ivanov, a Soviet intelligence officer and naval attaché. But not with both. With the Cold War at its height and fears that British security had been compromised, the scandal threatened to bring down Harold Macmillan's Conservative government.

Morley, whose talents extended into innovative fashion shoots, journalistic work, painting and sculpture, came to resent the power this one image had in overshadowing his other work, referring to it in later life as "that fucking Keeler shot". Keeler, too, came to dislike the picture. Exasperated at times, Morley later parodied it by photographing himself in the Keeler pose, astride a chair, but with a millstone around his neck. The shot was never made public.

The shot of Keeler came about after she had signed a contract requiring her to pose nude for publicity photos for a film. Although she was reluctant, the producers insisted. Morley sensitively cleared the studio and turned his back so that Keeler could undress, suggesting she sit astride the chair so the back would shield her torso. With the 30-minute shoot coming to end, Morley walked away. Turning, he noticed her "in a perfect position" and clicked the shutter once more; it was the last shot of the 36-exposure film and it was "perfect". Morley had inadvertently created the era's defining image, and made his name. "I never found her sexy," he later said. "She reminded me too much of Vera Lynn!"

Born in Hong Kong in 1925, Morley was the son of an English pharmacist, also Lewis, and a Chinese mother, Lucie Chan. He had a relatively privileged upbringing, raised as part of Hong Kong's European colonial elite. Returning from a short trip to Australia in 1940 the family were interned in a camp for the duration of the Japanese occupation. He had "a good war," he said. "I was the only able-bodied male in a women and children's prison – and worked in the kitchen! I also had a girlfriend."

After the war the family was repatriated to London, Morley serving two years' national service in the RAF, where he also dabbled with photography. He then studied commercial design at Twickenham Art School before moving to Paris in 1952 to study life drawing and painting – his passion – at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. He married a fellow art student, Patricia Clifford, the same year.

It was not until 1957, the year of his son's birth, that Morley's first photographs, a six-page spread, were published in the influential Photography magazine. The following year his first picture appeared in Tatler, where he became a regular. Assignments also came in for Go! and She magazines. Soon after, Lindsay Anderson asked him to take promotion stills for his production of Serjeant Musgrave's Dance, and he went on to shoot front-of-house images for more than 100 Royal Court shows, capturing many of the era's emerging talents including Anthony Hopkins, Peter O'Toole, Maggie Smith and Judi Dench.

His reputation burgeoning, Morley photographed Beyond the Fringe in 1960 and became friends with Peter Cook, who offered him studio space above his night club, The Establishment. He also photographed the circle that formed around the new satirical magazine Private Eye. With a one-room studio, in the heart of bohemian Soho, and an intuitive feel for the cutting edge, Morley established himself, publishing the first photographs in the fledgling careers of models Jean Shrimpton and Twiggy, actors including Michael Caine and Charlotte Rampling and the playwright Joe Orton.

Morley attributed some of his success to the influence of cinematography. "I started going to the cinema from about four or five years of age," he recalled. "By the time I was 15 I was conversant with the works of DW Griffith and other lesser Hollywood directors. Later, Fritz Lang and Carl Dreyer had a great impact on my sensibilities. The memories of those early experiences are still vivid." This perhaps explains why his pictures of the 1968 anti-Vietnam war demo in London's Grosvenor Square are particularly acclaimed.

In 1971, prompted by his friend, the designer Babette Hayes, Morley and his family emigrated to Australia: "I left London and the Sixties behind only to find the Sixties had just arrived [there]." Over the next 15 years Morley worked for Hayes producing colour commercial work for a variety of flagship publications including Belle, Pol and Dolly until 1987, when he retired.

In 1989 the National Portrait Gallery in London staged the exhibition Lewis Morley: Photographer of the Sixties, which then toured Britain. His memoir Black and White Lies appeared in 1992. He was appointed to the Order of Australia in 2010.

Earlier this year, rather than see his substantial archive of tens of thousands of photographs and personal papers auctioned off, Morley donated them to the National Media Museum in Bradford. It constitutes an extraordinarily detailed account, in pictures and words, of a fraught and ostentatious era in British social history.

Martin Childs

Lewis Morley, photographer: born Hong Kong 16 June 1925; married 1952 Patricia Clifford (died 2010; one son); died Sydney 3 September 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments