Lee Evans: Record-breaking sprinter who raced to victory during the 1968 Olympics

The athlete, who set longstanding world records in the 400m and 4x400m races, used his platform to protest against racial inequality

Lee Evans, who set a world record in the 400m run during the 1968 summer Olympics after two of his teammates had been kicked off the team for a victory-stand protest supporting black rights, has died aged 74.

Evans was a member of a 1968 Olympic team that excelled on the track but also sought to raise awareness of racial inequality during a year of social unrest, after assassins felled Martin Luther King Jr and senator Robert F Kennedy.

Alongside Harry Edwards, Evans helped organise the Olympic Project for Human Rights, which included his fellow sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who were also his teammates from San Jose State University in California. The project was begun, in part, to draw attention to housing inequities for black students, but it grew into a movement that challenged the hidebound leadership of the Olympic Games.

The black athletes had contemplated a boycott to publicise their cause, before deciding that the most potent way to put their message across would be to beat the rest of the world on the track.

“Winning was related to what was important to me,” Evans later explained: “Black pride and the cause of social justice.”

In the 200m race at the summer games in Mexico City, Smith and Carlos placed first and third. On the medal stand, they wore black socks without shoes to symbolise black poverty, then raised their black-gloved fists during the playing of the national anthem while gazing downward.

The protest was greeted with outrage by Olympic officials, most notably Avery Brundage, an American who was president of the International Olympic Committee. Brundage demanded that Smith and Carlos be removed from the US delegation, threatening otherwise to ban the entire US track team.

“They violated one of the basic principles of the Olympic Games: that politics play no part whatsoever in them,” Brundage said.

At first, Evans decided not to run in the 400m final as an act of solidarity with his teammates. But Smith and Carlos “came up to me”, he told The Washington Post in 1996, “and said, ‘You better run and you better win.’”

The 400m final was scheduled for 18 October, a day with intermittent storms. The stadium “seemed to shine in a clear, unearthly light”, US marathon runner Kenny Moore wrote in Sports Illustrated in 1987.

While Evans and other runners were preparing for their race, the long-jump competition was taking place. American Bob Beamon made an astonishing leap of 29ft 2.5in to shatter the existing world record by almost 2ft.

The 400m race was delayed as people in the stadium grasped the magnitude of Beamon’s feat. “I wondered what happened over there,” Evans told The Post. “He ended up on the track, crying in Lane 6. That was my lane. I said, ‘Bob, get off the track.’ He held up our race for about five minutes.”

Evans got off to a fast start in the race, covering the first 200m in 21.4 seconds. Once he rounded the final turn of the one-lap race, he tried to maintain his form, pumping his knees and arms, knowing he would be gasping for breath at Mexico City’s 7,500ft altitude.

“When we hit the straight, I figured I was five yards ahead,” he told Sports Illustrated – but off to his left, he could see his teammate, Larry James, running stride for stride with him. “With Larry there, I felt the bear clawing my legs,” Evans said, referring to the pain of exhaustion. “I felt faint.”

As they neared the finish line, he saw James put his head down. “I knew I had it then,” Evans said. “I powered through – ugh, ugh, ugh. Larry ran 395m. I ran 401. That was the difference.”

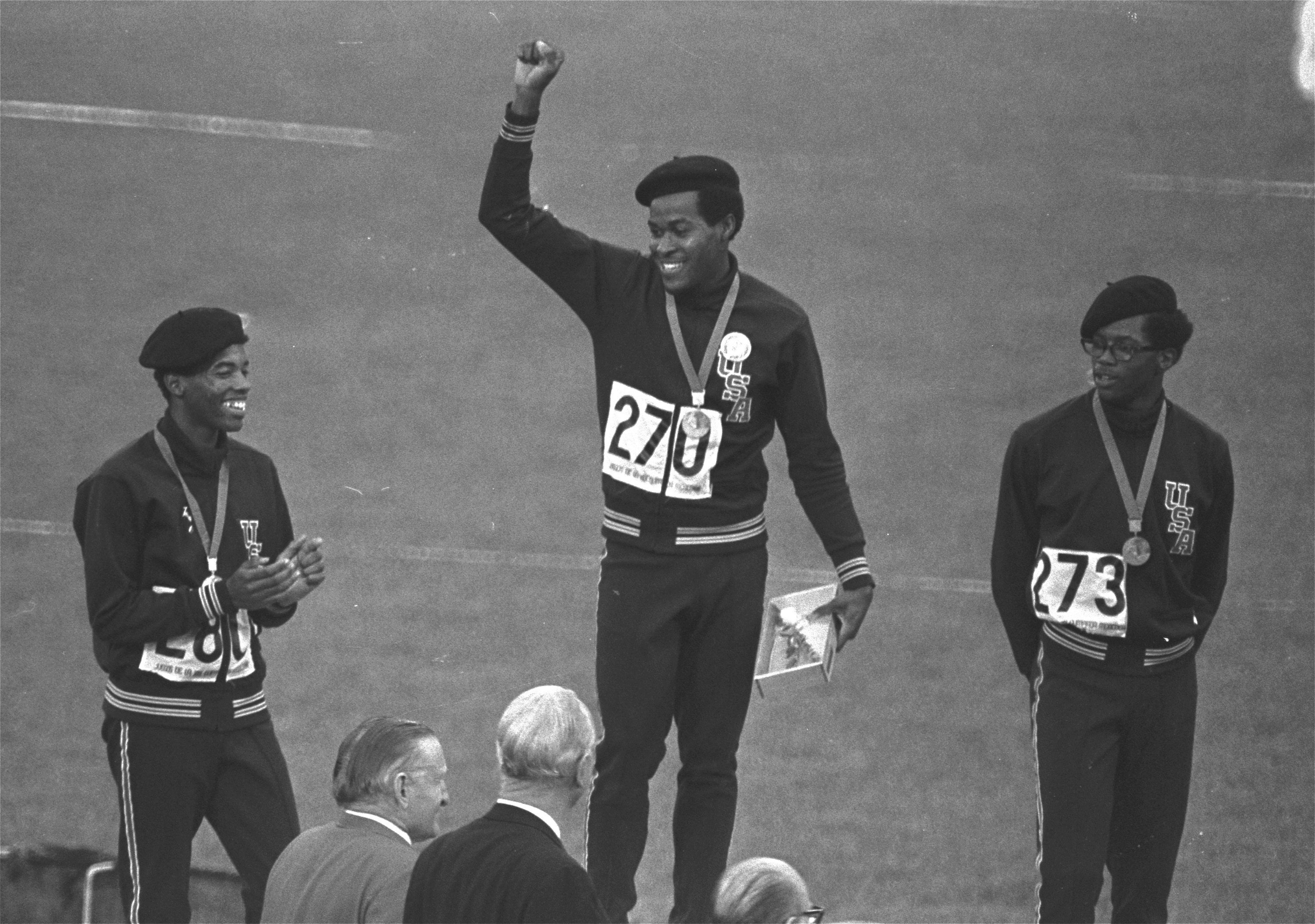

Evans had set a world record with a time of 43.86 seconds; James was second at 43.97. It was the first time anyone had run 400m in less than 44 seconds. Another African American runner, Ron Freeman, won the bronze medal.

As they took their places on the podium, all three were wearing black berets, which they removed for the national anthem. Afterwards, they raised their fists and smiled, but their demonstration did not provoke the uproar that Smith and Carlos had sparked.

“I feel I won this gold medal for the black people in the USA,” Evans said, “and black people all over the world.”

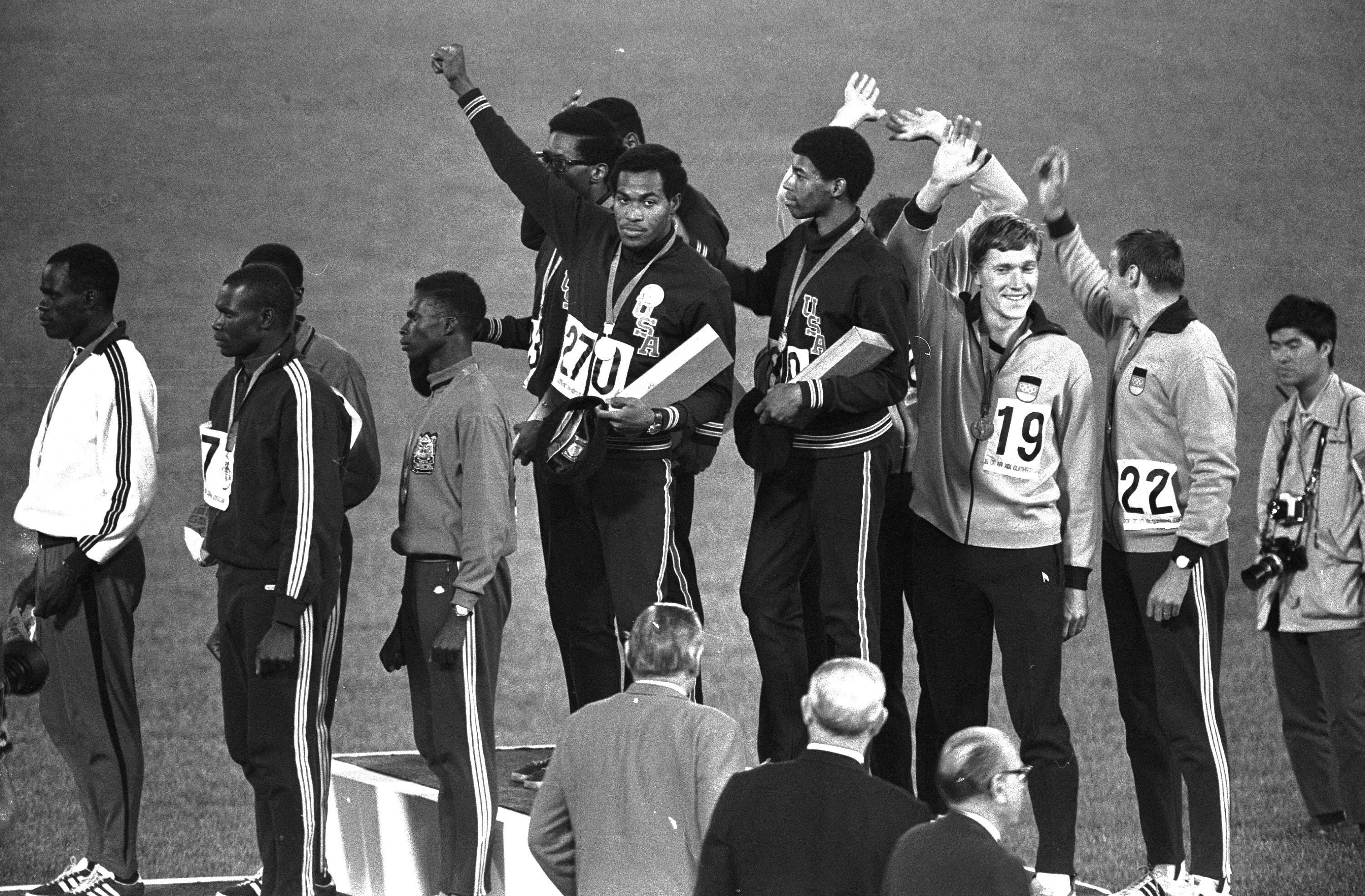

One day later, he ran the anchor leg of the 4-by-400m relay, as the American team won by 30m in 2:56.16. They broke the old world record, which Evans had helped set in 1966, by more than three seconds.

He and his teammates – James, Freeman and Vince Matthews – stood bareheaded for “The Star-Spangled Banner”, then donned their berets and walked away with their fists held high.

Lee Edward Evans was born on 25 February 1947, in California. His father worked in construction, and his mother sometimes worked in cotton fields, where young Lee also worked.

In high school in San Jose, Evans blossomed into an outstanding runner at every distance from 220 yards to 880 yards. (Most track meets in the US were run in yards until the 1970s, when they converted to the metric system.)

His best event, however, was the quarter-mile (440 yards, slightly longer than 400m). At San Jose State, he was coached by Bud Winter, who built such a formidable team of sprinters that San Jose was called “Speed City”. Evans, who graduated from San Jose State in 1970, also developed a strong racial conscience in college, in part from the teaching and advocacy of sociologist Harry Edwards, then on the university faculty.

Evans was the top-ranked 400m runner in the world from 1966 to 1968, and again in 1970. He won the 1968 intercollegiate title at 400m and was a five-time Amateur Athletic Union national champion. He helped set world records in the 4-by-200m and 4-by-220-yard relays, and also established a world record in the 600m run in 1968.

Evans was living in Madagascar in 1988, prospecting for gemstones, when he learned that his 400m mark of 43.86 seconds had been broken after 20 years by US runner Butch Reynolds. The world record Evans helped set as a member of the Olympic 4-by-400 relay team lasted until 1992.

Evans won a place on the 1972 US Olympic team as a relay runner, but did not compete after other runners were disqualified for a podium protest.

He ran on a professional track circuit until the mid-1970s, when he began coaching, primarily in African and Middle Eastern countries. He coached a Nigerian 4-by-400m relay team to an Olympic bronze medal in 1984.

He also developed training programs for US Special Olympics efforts and coached at San Jose State, the University of Washington, and the University of South Alabama before returning to Africa in 2008.

In 2014, he was suspended from coaching in Nigeria for four years after a 16-year-old female runner he trained tested positive for performance-enhancing drugs.

Evans was married three times and had at least four children. A complete list of survivors could not be confirmed.

Evans was a Fulbright fellow, worked for the United Nations in Africa in later years, and won a place in the US Olympic Hall of Fame and the US Track and Field Hall of Fame. After his Olympic triumph in the 400m in 1968, Evans was asked why he and his teammates raised their fists in the air. “Different people have different ways of saluting,” he said.

Lee Evans, sprinter and activist, born 25 February 1947, died 19 May 2021

© The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.