Kurt Masur: Conductor who played a crucial peace-making role in the last days of Communist East Germany

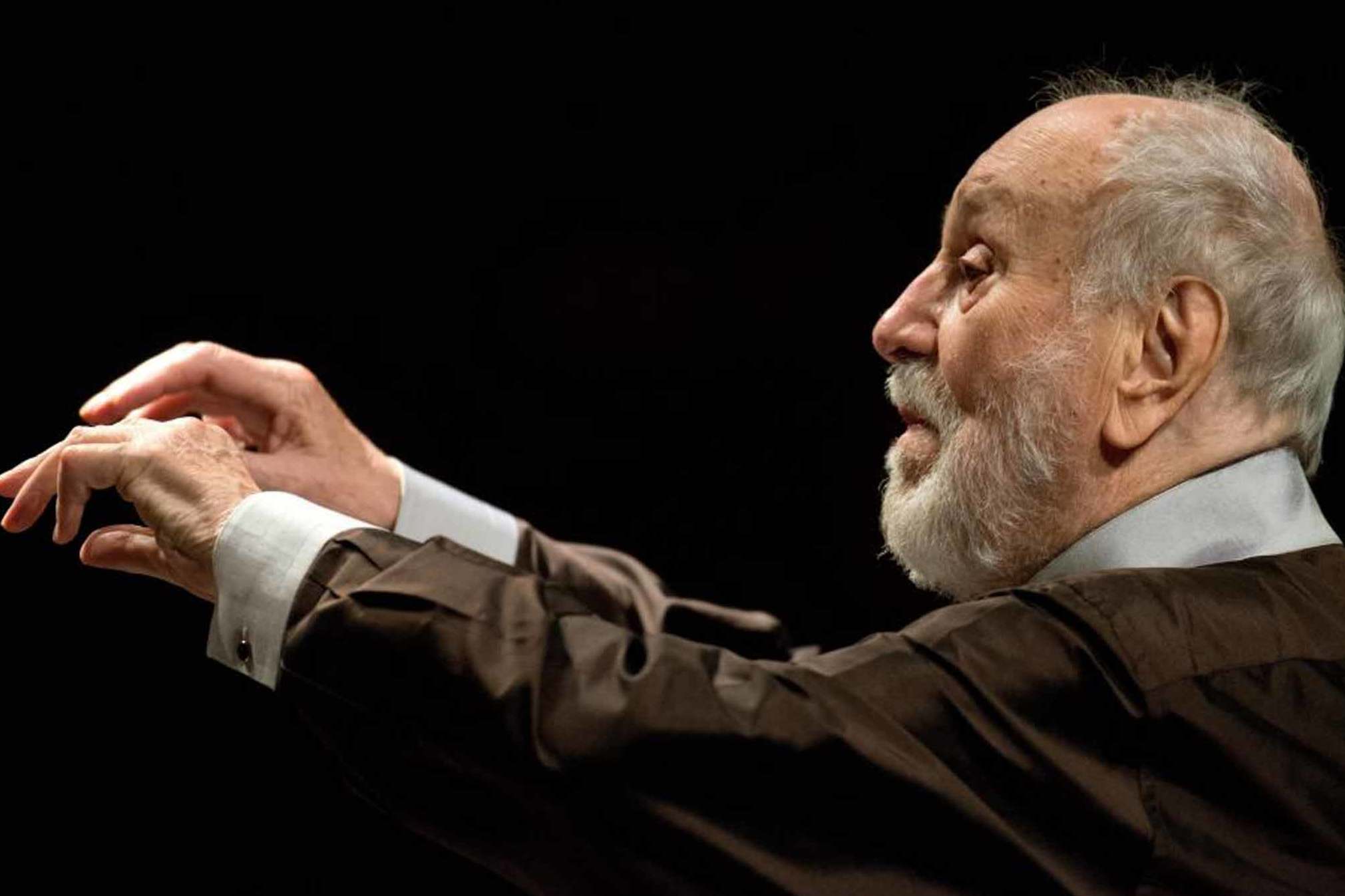

Masur conducted without a baton but left no one in doubt of his authority

The conductor Kurt Masur, who led the London Philharmonic for seven years and the New York Philharmonic for 11, manifested the healing power of music during tense political moments in his native East Germany, when he played a crucial peace-making role in the weeks before the collapse of communism and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Masur spent much of his career in East Germany, gaining international renown as music director of Leipzig's Gewandhaus Orchestra. He took over the orchestra in 1970 and built it into an ensemble of impeccable precision, known especially for its refined string sections. The orchestra recorded on major labels, and Masur also led a music school in Leipzig and taught courses in conducting.

A 1974 concert tour took Masur and the Gewandhaus to Carnegie Hall, prompting the New York Times critic Harold Schonberg to declare, “The ensemble was perfection.” Propelled into the top ranks of the world's conductors, Masur began to make guest appearances with orchestras in Chicago, Cleveland and Boston. He became principal guest conductor of the Dallas Symphony in the late 1970s but maintained his allegiance to the Gewandhaus.

Although he never joined the Communist Party, Masur prevailed on the East German leader Erich Honecker to support the building of a new concert hall in Leipzig and to rescind a government ban on travel outside the country by East German artists. As the pro-democracy movement gathered strength in 1989, Leipzig became a centre of resistance. After witnessing the violent arrests of demonstrators, Masur went on West German television and declared, “I am ashamed.”

On 9 October 1989, Leipzig's streets filled with protesters. Armed with the moral authority of his leadership of the Gewandhaus, Masur convened a meeting of dissidents, musicians and communist officials to draft a statement calling for non-violence. Against the orders of the authorities, the local police commander ordered his officers to withdraw. Masur went on Leipzig radio stations, pleading for restraint. He was seen as a calming force at a crucial moment.

A month later, the Berlin Wall came down: “Something happened here, before our eyes in Leipzig,” Masur said at the time. “This was not a revolution for better groceries, but for the spirit of freedom.” Some urged Masur to run for mayor of Leipzig or even prime minister, but he returned to the podium. On 31 December 1989 he led the Gewandhaus Orchestra in a triumphant performance of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, broadcast on television across throughout East and West Germany as a symbol of national unity.

“I am a politician against my will,” Masur he said. “I have the most wonderful profession a person can have. I'm not cut out to be a politician. I only tried to stop something bad.”

Masur was born in 1927, in what was then the German town of Brieg, now Brzeg, Poland. His father was an engineer who advised his son to study electronics. But Masur was drawn to music and began to teach himself the piano when he was seven. He later studied the organ, cello and other instruments.

At 15 he entered a music school in Breslau (now Wroclaw, Poland), and often listened to classical performances on the US Armed Forces Radio Network during the Second World War. Conscripted into the German army, he was captured and spent time in a British prisoner-of-war camp.

After the war, he turned to conducting because of an injury to his hand. He graduated in 1948 from a Leipzig conservatory founded by Felix Mendelssohn. He worked as a conductor at various opera houses and East German orchestras before going to Berlin in 1960 as music director of the Komische Oper [Comic Opera], where he developed a deep sense of the dramatic possibilities of music.

He began to take guest-conducting jobs and in 1967 became music director of Dresden Philharmonic. Three years later he moved to Leipzig, a city with a rich musical tradition. In 1991, Masur took over as music director of the New York Philharmonic. He brought a Germanic sense of discipline to the orchestra, which had given years of lacklustre performances under his predecessor, Zubin Mehta.

Masur conducted without a baton but left no one in doubt of his authority. He specialised in 19th century repertoire, but he also commissioned dozens of new works by American composers. He brought a new clarity to the orchestra's sound and embarked on ambitious recording projects and a series of worldwide tours.

Much of his 11-year tenure at the New York Philharmonic was marred by a power struggle with the orchestra's board and its executive director, Deborah Borda. In 1998, the board announced that Masur would leave after four more years. He was furious about the decision, saying his prickly dealings with the Philharmonic reminded him of his earlier experiences with the East German secret police.

When Masur left the Philharmonic in 2002, he had conducted about 860 concerts for the orchestra. He had been appointed principal guest conductor of the London Philharmonic in 1988, and served as its principal conductor from 2000 until 2007. One of the LPO players recalled, “When Masur's conducting you think, 'Why can't everyone conduct like this?' He's not dictatorial - it's just musical common sense. He makes the orchestra feel they have a common purpose.”

For Masur, music was a form of idealism, a way to inspire people to reach for transcendence and truth. “The message of Beethoven brings us back to what we should do,” he said in 2004. “Fear can never unite people. Pain cannot unite people. Joy unites people. Beethoven is always fresh.”

Kurt Masur, conductor: born 18 July 1927; married three times (two daughters, three sons); died Greenwich, Connecticut 19 December 2015.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments