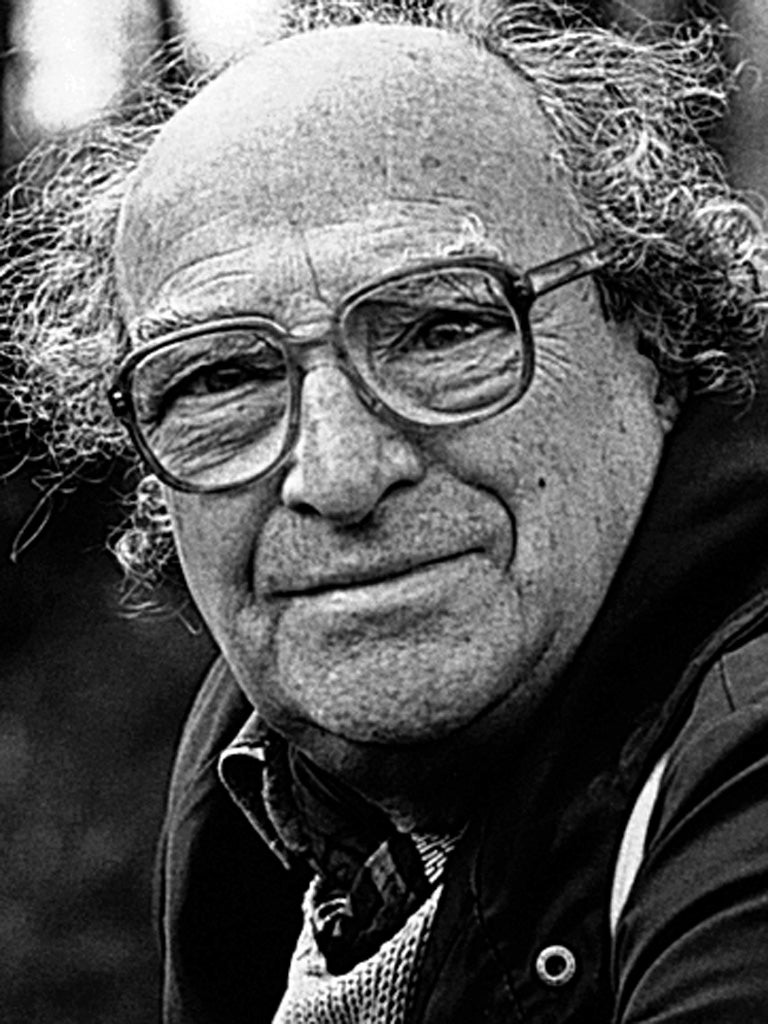

Ken Graves: Industrial journalist and trade unionist

There are few journalists who had a contacts book that Fleet Street would have killed for, but the Morning Star's industrial correspondent Ken Graves belonged to that select group. Born in Birmingham into working class family, he didn't get much of an education due to his father having to move around to get work. Like most young people until the Thatcher era, Graves was expected to get an apprenticeship in a factory, but when he was 15 a road accident broke one of his arms. This never healed fully, so restricted the work he would be able to do. He left school with no qualifications and set about educating himself with a gusto that was a trademark of his professional life.

He joined the British Communist Party during the Second World War and the party's education programme helped fill in the gaps in his schooling. He became a party organiser as well as a journalist on the Daily Worker, later relaunched as the Morning Star.

Graves excelled at building up contacts in factories throughout the Midlands which often lasted a lifetime. He was trusted by both sides of industry and regularly landed national exclusives. His work covering disputes helped to strengthen his belief in the William Morris ideal that workers could live in harmony with nature. His approach to live was based on a deep humanity to all his fellow men and women irrespective of religion, race creed or colour.

He married his wife Joan in 1962; his son David (1963-93) became one of the first pupils from a state school in Coventry to win an Oxford scholarship. Graves never had much money, but such was the respect in which he was held by the Labour movement that in 1969 friends raised the deposit on his house in Earlsdon, Coventry. From that day, he and his family were neighbours of mine.

I first met him in a professional capacity as a junior reporter on the Coventry Journal. He was never afraid to remind the TUC leadership and Labour front bench who they were representing. One thing we did agree on was that I should always follow Tony Benn's advice of telling the truth and keeping a carbon copy and my notebook.

In the 1970s, he started working for union papers, including the T&GWU Record. He was often unofficially invited into the Joint Shop Steward Committee meetings at many Midlands plants and he maintained his record for scoops. This included the sleeping bag dispute at Rover, the Ansell's Brewery strike and what the Edwardes' reorganisation plan for British Leyland really meant. The latter regrettably proved to be wholly accurate.

Disillusioned with the CP, Graves joined Coventry South Constituency Labour Party. This was partly because their MP, Jim Cunningham, had risen through the shop stewards' movement to become Leader of Coventry Corporation, which is still regarded as one of the more progressive local authorities.

When Tony Blair led the country into the invasion of Iraq, Graves immediately proposed a resolution calling for an Emergency Conference of the Labour Party to condemn the Prime Minister. Passions were high at the Party meeting and, typically of Graves, he bore no ill will towards those who voted to support Blair. He believed to the end of his days that ordinary people could better themselves via collective action through their trade unions or parties.

I found out early on that Ken Graves had a nose for a good pub. He once made me walk to another pub when covering a dispute because he knew that lorry drivers drank there – and they didn't put up with bad beer. He also enjoyed the countryside and spent family holidays in the Lake District. Anyone who accompanied him could affirm that he could find a real boozer in the middle of nowhere.

This helped fill the gap in his work when union amalgamations reduced the number of newspapers he could work for. He was editor of the Warwickshire Wildlife Trust's magazine formany years – his first scoop was the first red kite spotted in the county since records began.

Graves' proudest moments were when he was made an Honorary Life Member of the National Union of Journalists in July 1990; the T&GWU General Secretary Jack Jones presented him with Certificate to mark his 25 years' service to the union. He was a journalist for over 60 years and, no matter whether stories were big or small, he looked after them all.

Kenneth Graves, trade unionist, journalist and politician: born Birmingham 31 January 1923; married 1962 Joan (one son, deceased); died Coventry 9 January 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments