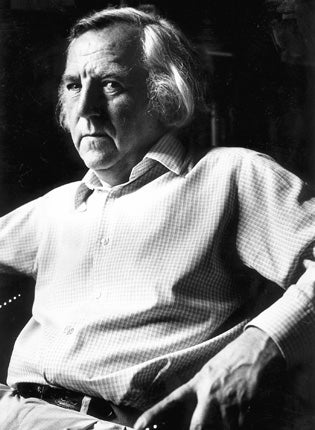

Keith Waterhouse: Celebrated columnist and writer best known for 'Billy Liar' and 'Jeffrey Barnard Is Unwell'

The last of the 2000-plus articles that Keith Waterhouse wrote for the Daily Mail was published just a month ago. Appropriately enough, it celebrated the 50th anniversary of the publication of Billy Liar, his hilarious and engaging novel that became a hit play, a film, a musical and a television series. Although his principal profession and passion was journalism – and nobody did it better – it is for Billy Liar that he is likely to be longest remembered.

It was his second novel. His first, There is a Happy Land, was published in 1957, when he was 28. As he wrote in the Mail article: "A first novel is an indulgence, and is indulged; a second tells the world that you are re-entering the ring as a serious contender."

Billy Liar went through several drafts, one of which he left in a taxi and never saw again. What eventually emerged was the story of an inveterate fantasist who worked as an assistant to an undertaker, as Waterhouse once had. It was enthusiastically received, allowing no doubt that he was now a very serious contender indeed.

Not long after its publication the playwright Willis Hall – whom he had known as a youth in his native Leeds – suggested that they should collaborate to put it on stage. The play ran for 582 performances. Albert Finney took the leading role for nine months, to be replaced later in the run by Tom Courtenay. Its success marked the start of a long and fruitful collaboration between Waterhouse and Hall: together they wrote a dozen West End plays, as well as a number of film scripts.

Billy Liar made Waterhouse a wealthy man. "For a while I dabbled at being seriously rich," he wrote. "Hand-made boots from Lobb's, gold Omega watch, Calibri lighter, expensive casuals, mink in the adjoining wardrobe, hire cars everywhere, outrageously priced dinners at the White Elephant. Except for a daily bottle of champagne, for which I have retained the taste, such excesses soon palled."

All this was in contrast to his upbringing in a working-class suburb of Leeds. His father sold groceries from a barrow and his mother was a cleaning lady. The youngest of their four children, he attended Osmond-thorpe Council School and then Leeds College of Commerce, before quitting education at 14.

He took a job as an undertaker's clerk (J.T. Buckton and Sons – We Never Sleep); but his ambition was to become a journalist, and he sent articles on spec to the Yorkshire Evening Post. Although they went unpublished, the editor was impressed by his unflagging determination and offered him a job after he completed his National Service in the RAF in 1949.

This first aim achieved, he quickly reset his sights towards London. In 1952, when he thought he had gained enough experience in Leeds, he took himself to Fleet Street, knocking on editorial doors, until he was offered a post on the Daily Mirror. On the application form he was asked to state his ultimate ambition. His response was that he wanted to succeed Bill Connor, who wrote a much-admired column for the paper under the by-line "Cassandra".

But Connor was still going strong and Waterhouse was taken on as a reporter. Among his prominent assignments was to write a series in 1956 called "The Royal Circle". He argued that, three years into the so-called New Elizabethan age, "the circle surrounding the Queen is as aristocratic, as insular and – there is no more suitable word – as toffee-nosed as it has ever been". The court, he found, still consisted largely of peers and their relatives, old Etonians and Guards officers.

Iconoclasm was a theme that would permeate his writing throughout his career. Despite that one brief flirtation with the world of gold watches and mink, he was instinctively opposed to elitism, to pomp and circumstance and to pretension in all its forms.

Bill Connor died in 1967 but Waterhouse had to wait until 1970 before he was asked to take over the Mirror's twice-weekly column. He immediately made it his own, sometimes commenting waspishly on the issues of the hour and sometimes building a compelling and entertaining argument out of a seemingly trivial incident from his everyday experience.

He was against bureaucracy, especially the bureaucracy of petty officialdom: he wrote a memorable column one Christmas Eve, viewing the Nativity through the eyes of three wise social workers appalled by conditions in the holy manger and determined to take the new-born infant into care. He invented two shopgirls, Sharon and Tracey, whose indifference to their customers and their banal conversations illustrated what he saw as the vacuity of much of modern life.

He was also an enthusiastic campaigner for the correct use of English, and was asked to write a style book for the Mirror. Like all such manuals, it was more honoured in the breach than the observance among its initial target audience but, published later as Waterhouse on Style, it became a best-seller. He returned to the theme in a later book, English our English (and how to sing it).

One of his classic columns – the one that the Mail chose to reprint to mark his death last week – announced the formation of the Association for the Abolition of the Aberrant Apostrophe: "The AAAA's laboratories have identified it as a virus, probably introduced into the country in a bunch of bananas and spread initially by greengrocers, or greengrocer's as they usually style themselves."

Writing in 2004 in the British Journalism Review, whose readers had just voted him the best of contemporary columnists, he set out some of the requirements of his craft: "Along with the standard journalistic tools such as Nicholas Tomalin's rat-like cunning, plus the ability to read documents upside down, the columnist should not embark upon his trade until he has accrued a stockpile of information, useless or otherwise, that would shame a magpie's nest. Did I say useless? Nothing is useless to the columnist... An elephantine memory helps. The columnist should not only be a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles, he should remember where he put them."

By the time he wrote that, he had long left the Mirror for the Mail. The painful break with his old paper came not long after it was acquired by Robert Maxwell in 1985. In a reversal of standard protocol Waterhouse invited Maxwell and the editor, Mike Molloy, to lunch with him at a swank Mayfair hotel. It was a reflexion of his influence and prestige – and his notoriety as a luncher – that the self-regarding proprietor agreed to be his guest rather than his host.

Lunch was, for him, a ritual observance. In his Who's Who entry he named it as his sole recreation and one of his many books is devoted to the celebration of it. In a radio interview he stressed that the significance of lunch had nothing to do with what was eaten – the prawn cocktail, the steak, the Black Forest gateau – but that it "should be a holiday without the hassle of flying". Sometimes these well-lubricated mini-breaks would last well into the afternoon, which was why his daily routine involved doing most of his work in the morning.

Yet on this particular occasion the lunch did not bring about the hoped-for harmony between the tycoon and the columnist. Maxwell was too much the interfering proprietor for Waterhouse's taste, and when David English, the editor of the Mail, invited him to jump ship, he did not hesitate.

His switch of allegiance came at a seminal time in the history of the British press. Developing technology meant that newspapers no longer had to be printed where they were written and all the national titles were preparing to move away from their traditional homes in and around Fleet Street.

This meant the end of the old freemasonry, the exchange of opinion and gossip in long sessions in the local pubs. Like many newspapermen of his generation, Waterhouse felt that this aspect of the job had been central to it, and he mourned its loss. In 1990 he wrote: "The continuing debate was an essential feature of Fleet Street, the awful pubs were the forum where people talked and a lot of the talk was rubbish but we learned a lot from it too. This just doesn't happen any more. Now I have a computer, my stuff goes straight from screen to screen; I no longer need to go anywhere near Fleet Street."

For more than 20 years he continued to contribute his feisty, impeccable columns to the Mail twice a week, winning several professional awards as well as a CBE. He stood down last May, less than four months before his death.

Throughout his career he also kept up a prodigious output of books and plays – he told an interviewer that in his time he had written in every form except verse and advertising copy. His most successful play, after Billy Liar, was Jeffrey Barnard is Unwell, which he wrote in 1989, this time without Hall's input.

The fictionalised account of the misadventures of a notoriously bibulous real-life journalist and rake elicited a memorable performance from Peter O'Toole, and has often been revived. Waterhouse's last play, The Last Page, concerns the demise of the Fleet Street he loved, and is yet to be staged.

Given so demanding a work and social schedule, it was scarcely surprising that his personal life was seldom harmonious and at times chaotic. In 1950, when only 21, he married Joan Foster, and they had three children. As his fame increased the couple drifted apart and eventually divorced.

In 1984 he married Stella Bingham, a talented journalist. That too ended in divorce; but in the last decade of his life they came together again. As his health deteriorated Ms Bingham took it upon herself to care for him, and it was largely due to her ministrations that he was able to work right to the end.

Michael Leapman

Keith Spencer Waterhouse, writer: born Leeds 6 February 1929; CBE 1991; married 1950 Joan Foster (three children), 1984 Stella Bingham (divorced); died London 4 September 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments