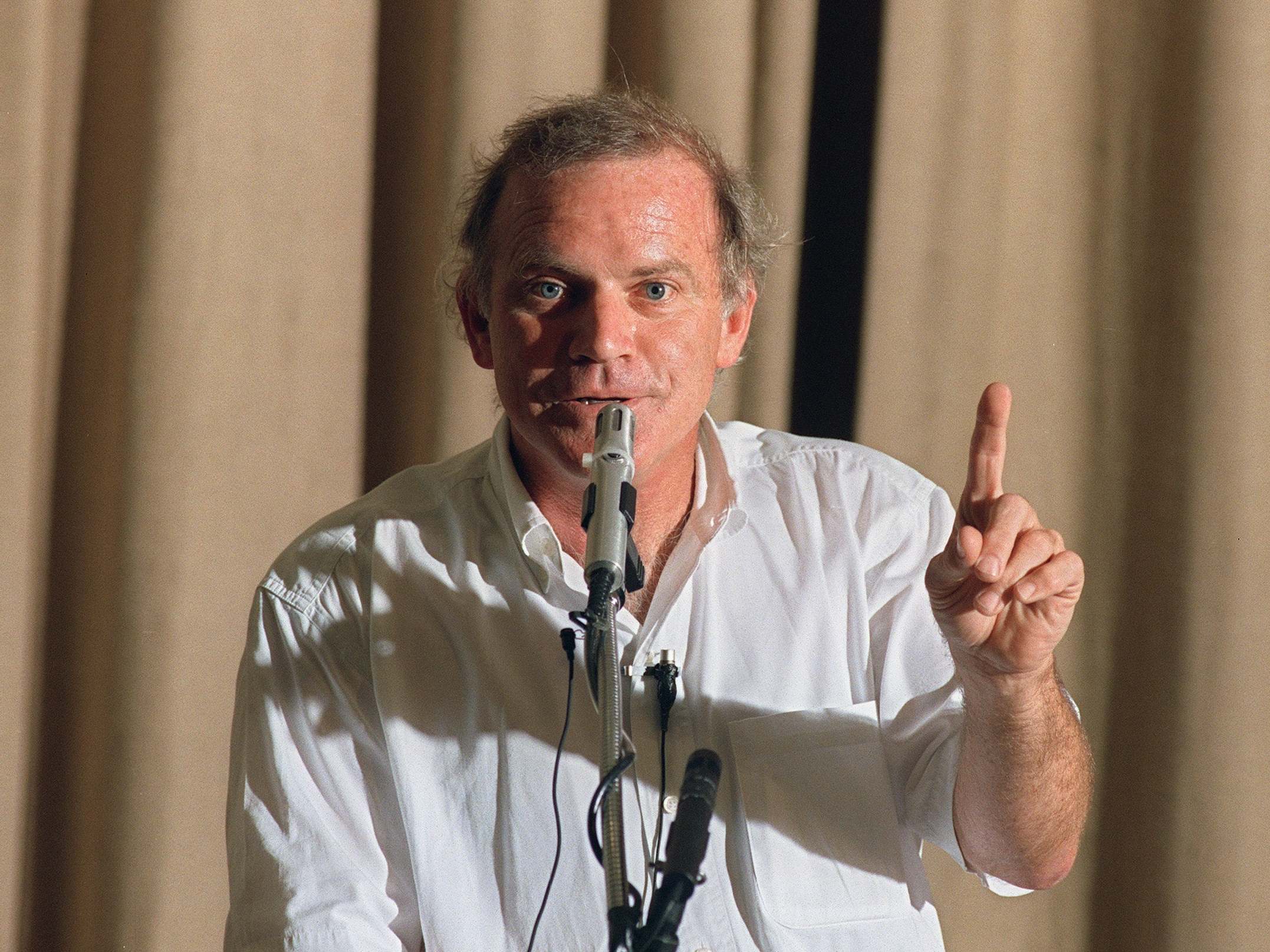

Kary Mullis: Unconventional Nobel laureate who unlocked DNA research

His work proved to be a milestone in biochemistry, but his views on climate change and Aids made him an outlier in the scientific establishment

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Kary Mullis shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for devising a technique vital in DNA research and technology, and could claim to be one of the most unconventional winners of the award.

Mullis, who has died of pneumonia aged 74, shared the prize in 1993 for the technique known as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which enabled scientists to make millions or billions of copies of a single tiny segment of the DNA molecule. Often described as a major milestone of 20th-century biochemistry and molecular biology, the PCR technique opened the way for a wide variety of studies and applications of DNA, the molecule that lies at the foundations of life.

In only one of many applications, PCR was used by evolutionary biologists to study the minuscule quantities of DNA discovered in the fossils of ancient species. The possibilities suggested by this technique inspired the creation of dinosaurs in such fictional films as Jurassic Park (1993).

Widely acknowledged for its significance, PCR not only rewarded Mullis with the most coveted prize in science, but it provided him with a platform that he bestrode with relish for his free-spirited, often quirky ideas and lifestyle.

A writer, a surfer and a restless, questing personality who once turned from science to manage a bakery, Mullis published a memoir entitled Dancing Naked in the Mind Field (1998). It embellished his reputation for happily ignoring the normal strictures, cautions and conventions that were observed by so many others in science and scholarship, particularly those at the exalted levels of Nobel winners.

It is true that, despite the title of his memoir, he did not appear unclothed on its dust jacket. But few if any other Nobel winners published anything showing themselves bare-chested with a surfboard tucked under an arm.

Among the exploits and adventures for which he was known was experimentation with LSD. It was this that reportedly made the defence team representing OJ Simpson – the former American football star and actor acquitted in 1995 on charges of murdering his ex-wife and her friend – decide against calling him as an expert witness. Although that trial has often been depicted as a courtroom circus, Mullis once told an interviewer that it was feared that his appearance might have only made the proceedings seem more of one.

A 1966 chemistry graduate of Georgia Institute of Technology who earned a doctorate in 1973 from the University of California, Berkeley, he appeared in many ways to be one of the most prominent representatives in the scientific community of the mindset of the counterculture that was centred in California in the 1960s.

In his Nobel lecture, he told the assembled dignitaries that “six years in the biochemistry department didn’t change my mind about DNA, but six years of Berkeley changed my mind about almost everything else”.

A fount of ideas sufficiently offbeat to make fellow scientists frown, he seemed sceptical of much conventional wisdom, including theories that were widely held in science. Doubts about whether climate change was human-made or whether HIV caused Aids helped to make him seem an outlier in the scientific establishment. In addition, his apparent enthusiasm for astrology and seeming fondness for such ideas as astral projection and the possibility of abduction by aliens also led his scientific peers to look askance at him.

Kary Banks Mullis was born in 1944 in Lenoir, north Carolina, and started life near the Blue Ridge Mountains. When he was about five, the family moved to Columbia, South Carolina. At school there he demonstrated an interest in science and scientific exploration by launching rockets, powered by homemade chemical fuel.

After receiving a doctorate in biochemistry from Berkeley, Mullis did research at other universities before joining Cetus Corp, then a San Francisco Bay area biotechnology firm, where he said he “was working when I invented PCR”. He later became the chief of molecular biology for another corporation, Xytronyx Inc, in San Diego. Subsequently, he worked as a freelance consultant.

He is survived by his third wife, Nancy Cosgrove Mullis, and three children.

Kary Mullis, scientist, born 28 December 1944, died 7 August 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments