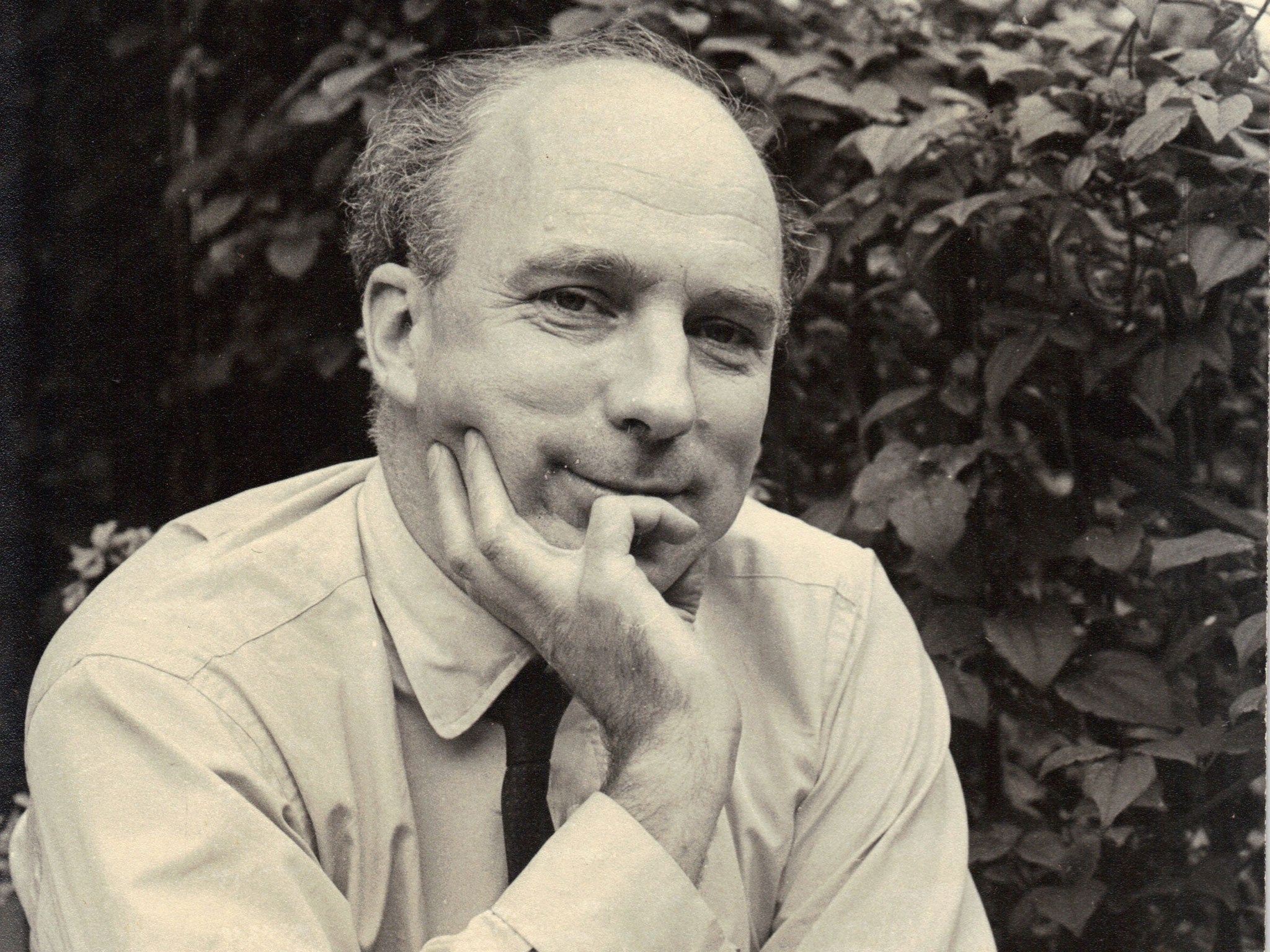

Justin de Blank: Entrepreneur who became one of the pioneers of the 'foodie' revolution

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Justin de Blank was one of the leaders of the revolution in eating habits that has so improved the lives of middle-class Britons since the 1970s. His name on a food product was a guarantee of its quality, whether his own-recipe sausages, or the sandwiches sold by Tesco, or the quiche or ratatouille made for him by a posse of home cooks and sold at his shop in Belgravia, London.

His Dutch grandfather, Joost de Blank, had been responsible for getting the Roman Catholic Rijkens family and the Jewish Van den Berghs to join forces in the Margarine Union in 1927, then persuading them to join in a conglomerate with Lever to form Unilever two years later. An uncle by the same name (the Dutch form of Justin's name) was the celebrated anti-apartheid Archbishop of Cape Town. While the family was living in Ealing, west London, Justin's Dutch father, William, met his Scottish-English mother, Agnes Crossley, at a tennis club in Holland Park.

Justin, born in Ealing in 1927, was sent first to Grenham House School, Birchington-on-Sea, and then to Marlborough College. He did a short course at Reading University then went up to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where he read Architecture and was part of the same set as Anthony Armstrong-Jones (later Lord Snowdon). He did his National Service in the Navy and was proud that he won a cup for dinghy racing, having taught himself to sail from a book.

He trained as an architect at the Royal Academy School of Architecture and, though he never pursued a career as an architect, his family remembers his skill at erecting sandcastles so complex that he could put 10 golf balls on the various turrets and battlements, and they would all exit separately at the bottom of the structure.

He worked at Unilever from 1953 until 1958 as a trainee, and started a magazine for the company. This was followed by a spell in advertising at J Walter Thompson. De Blank was, says his second wife, Melanie, "a great pet of Sam Meek" (who had overseen a massive expansion in JWT's international business).

Meek made de Blank head of JWT in Paris until 1965, when he returned to London. The food critic Fay Maschler recalled that time: "I first met ... Justin de Blank when, as a young thing, I was a copywriter at J Walter Thompson. Working on the Kellogg's account ... I was sent out ... to accost women in the street and ask them if we could photograph and catalogue their store cupboards. Tiring quickly of the task, the photographer and I started substituting friends for the supposed random survey.

"I think it was the photo-essay on the writer Nell Dunn's kitchen cupboard that made Justin shake his head and give me a particularly old-fashioned look. He left JWT soon afterwards (as did I), and after a while I noticed that he had gone into the food business. Maybe those dismal cupboards played a part."

In 1967 de Blank worked briefly for Terence Conran's Design Group, setting up the mail-order scheme for Habitat. The following year, with a partner, Robert Troop, he founded his own company, when he opened, as Maschler recalled, "the eponymous delicatessen in Elizabeth Street – a gleaming good deed in a then very naughty gastronomic world – and also a small, refreshingly good restaurant in Duke Street, off Oxford Street, which was the first restaurant where I remember zinc being used for tabletops."

He called the company, of which he was chairman and managing director, Justin de Blank Provisions Ltd. The food sold in the shop was superior, some of it branded goods of the type then easily found in any French provincial town, but not so easily in Britain, and some of it the home-made produce de Blank commissioned from his network of Cordon Bleu cooks. The food was not the only attraction: in the September 2000 Petits Propos Culinaires, a reviewer remembered "those incredibly acceptable and attractive undergraduates that Justin de Blank used to people his stores with".

The shop remained a landmark until September 1994, when the Evening Standard commented: "Do not be surprised if the dowagers of Belgravia appear slightly pinched or drawn, or misty-eyed with stoically concealed grief: Justin de Blank, who has supplied them with cleverly sauced chicken breasts and fine cheeses for many a year, has reluctantly abandoned his Elizabeth Street shop."

De Blank said: "We closed 21 days before our 25th anniversary, which was a pretty bitter thing to have to do. Lloyd's has hit our customers hard, but the main problem was the big supermarkets' decision to start stocking rare foods. Little chaps with trilbies would come round writing down the names of our suppliers, then three weeks later the product would appear on some huge supermarkets' shelves. What can you do?"

In 1972 de Blank had married Molly Godet, an artist from Bermuda, who became an advertising creative director. They divorced, and in 1977 he married Melanie Irwin, who was more than 30 years younger. They met at the shop; she was one of the comely, well-spoken Elizabeth Street girls. In a 1998 interview, she said of that time: "Food is one of our mutual interests, as is a love of art, and I was frightfully impressed by someone who knew so much about everything. He was successful, well-known and a highly charismatic person to be entertained by, and about one and a half years later we married. Justin has been a huge influence on my food. He introduced me to all sorts of possibilities that I wouldn't have thought of – he's a complete original. Up to a point our relationship was one of mentor and pupil, then I went off in my own direction."

Together they ran an exquisite "restaurant with rooms", Shipdham Place, in Norfolk, where Melanie cooked. They had three daughters, and lived what the middle child, Martha, described as an idyll: "Although they were hugely ambitious, both were hands-on parents. Mummy cooked nutritious, organic meals for us well before it was fashionable. Daddy, who was over 50 when I was born, read us fairy stories and played wonderful games. Our time was divided between a 10-bedroom Georgian farmhouse in Norfolk and a family home in Belgravia. Our house thronged with such visitors as Prue Leith and Clement Freud. "

At 26, Melanie was diagnosed as having non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. She wrote a book about her experiences nine years later, after extensive medical treatment, when the disease was in remission.

By 1988 de Blank was running a fine-food empire. The Elizabeth Street emporium had been joined by the Hygienic Bakery in Walton Street, a wholesale bakery, a business called Imports and Frozen Foods, and the catering concession at the British Museum, the Tottenham Court Road and King's Road Habitat, Heal's, the General Trading Company and, in 1989, the Imperial War Museum, plus the old Justin de Blank restaurant at 54 Duke Street.

Then there were those Tesco sandwiches, from 1994, the year Elizabeth Street closed. In 1997 he started again, keeping the restaurant critics busy with a converted pub, the Stamford. Then, 25 years after Duke Street, he opened Justin de Blank Bar + Restaurant in Marylebone Lane. Jonathan Meades described de Blank teasingly as: "A charming arty herbivore in his sixties with the demeanour, dress and enthusiasm of, say, the pottery teacher at a progressive school 30 years ago."

About this time de Blank began manifesting the first signs of Parkinsonism and the businesses all failed soon after. But there is a lasting memorial to Justin de Blank's kindness, and his shrewdness, in the roll call of people he employed or to whom he gave their first start.

Paul Levy

Justin Robert de Blank, fine food merchant and restaurateur: born London 25 February 1927; married 1972 Molly Godet (marriage dissolved), 1977 Melanie Irwin (three daughters); died 17 December 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments