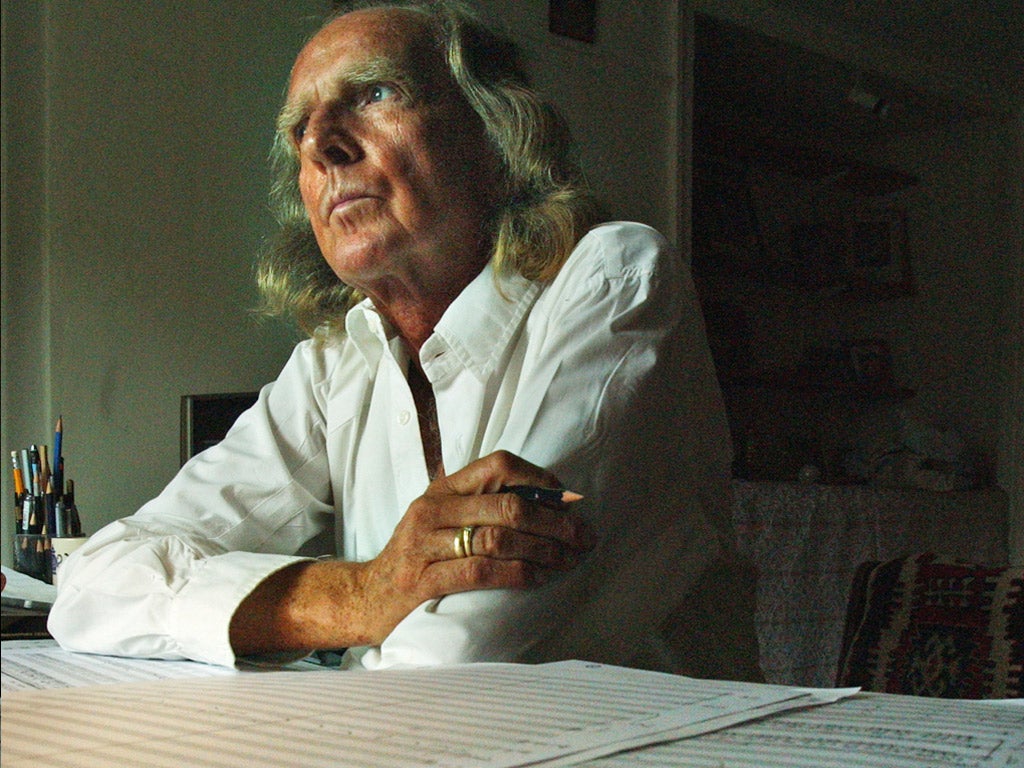

John Tavener: Musician whose work was informed by the spiritual fulfilment he found in the Russian Orthodox Church

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.John Tavener was one of a select number of "serious" composers who in the 1980s and 1990s won something like a wide audience for contemporary art music. Yet his conviction of the spiritual purpose of music was exceptionally serious and deeply traditional.

Tavener was born in Wembley Park, north London, in 1944. His family were Scots Presbyterians (genealogy may link him to the 17th century composer of the same name). They provided a religious upbringing and, over the years, emotional and practical support for his talents. He began playing piano while still young, entertaining his aristocratic godmother and her friend by creating musical portraits of them and improvising nursery rhymes in the styles of different composers.

He won a music scholarship to Highgate School, where he began composing for the school orchestra, and studied organ and piano. At the age of 12 he heard a broadcast of Stravinsky's Canticum Sacrum – one of the most important musical influences of his life and, retrospectively, a first glimpse of the Byzantine world which prove so decisive. "All I can say is that I idolised late Stravinsky after that," he recalled.

Tavener parallelled his school work with organ-playing at his father's church. "That made no spiritual impact on me whatsoever," he recalled, "except, I suppose, a sentimental love of hymns which I think I've just about lost. He also composed for the choir: a Credo, presented in November 1961, and then a short oratorio, Genesis, in 1962.

Later that year Tavener enrolled at the Royal Academy of Music. He planned to become a concert pianist (having already taken lessons with Solomon), but he was plagued by nerves and began to feel a temperamental distance from music in the Austro-German tradition. Halfway through the course he became certain that he wanted to become a composer. His teachers were Sir; Lennox Berkeley and David Lumsdaine; the latter introduced him to Boulez, Ligeti and Messaien. His time at the Academy was marked by precocious success. He made his public debut in his own piano concerto; staged a one-act opera, The Cappemakers; John Noble sang Three Holy Sonnets of John Donne; and the cantata Cain and Abel won the Prince Rainier II of Monaco Prize.

By the end of the 1960s both audiences and many young composers were tired of po-faced postwar music; they wanted more feeling, more vitality. Still in his early twenties, Tavener was throwing himself wholesale into the Swinging Sixties, in an avant-garde sort of way. He sported a pink suit and cruised around London in an aging Bentley; The Whale was his compositional equivalent of this flamboyancy.

Premiered in January 1968 in the inaugural concert of the London Sinfonietta, it combined lush string harmonies, Romantic piano music, tape and amplified metronomes with exotic percussion. The opening text is a lengthy extract from Collins Encyclopaedia; the piece proceeds via Vulgate Latin to an almost comic-book version of the Jonah story, including a graphic account of his emission from the whale's stomach.

The Beatles' drummer Ringo Starr was given a tape of The Whale; John Lennon and Yoko Ono met Tavener for dinner in Kensington, and they spent an evening listening to eachothers' music. Next day, Lennon telephoned, offering to record Tavener's works on their idealistic Apple label. Meantime, in 1969, Tavener became Professor of Composition at Trinity College, and, thanks to Benjamin Britten, was commissioned by the Royal Opera.

Just as his future seemed assured, Tavener began to find composition increasingly difficult. He left pieces unfinished, or completed them but found them unsatisfactory. One exception was Ultimos Ritos, on texts by St John of the Cross (1972). He arranged the musicians, symbolically, in the shape of the Cross, with the resting place and structural bedrock of the piece a taped quotation from Bach's B Minor Mass, a revelation which had come to him on the car radio during a country drive. The work won the prize for religious composition from the Italian Society for Contemporary Music.

Victoria Marangopoulou, a Greek dancer, became his wife in 1974, though the marriage lasted only a short time.

Tavener's initial source for his Royal Opera project was to be a Jean Genet novel, but he lost interest during one of his phases of composer's block. Eventually the spiritual agonies of St Theresa of Lisieux became his theme, using a libretto by the Irish-born playwright Gerard McLarnon.

In retrospect, Tavener's difficulties in composing may have been spiritual as much as musical. His Presbyterian background had not given him a religious experience. While at the Academy he had considered conversion to Catholicism, but was repulsed by its stress on punishment and hell. For years, though, he had been in contact with the Russian Orthodox church. McLarnon was a convert, and family friends had introduced Tavener to the Carmelite Father Malachy Lynch, through whom he met Metropolitan Anthony, head of the Church in the West. In 1977, after much soul-searching, this was the church to which Tavener converted.

From then on, his faith became the bedrock of his art. "Writing music becomes more and more, as I grow older, an act of prayer," he noted. "The act of composition makes me feel close to God."

For Tavener, this meant that his music had to embody a continuation of tradition. "He and many others adore the past," Britten had said years earlier, "and build on the past." Tavener's interest in tradition, however, was not in the sense that Britten intended. "I don't mean by tradition changing guards at Buckingham Palace," Taverner explained, "nor the classical music tradition with its fixation on the idea of artist as genius." For him the concept of genius was almost idolatrous. Instead, he sought to connect to tradition in a much earlier and to him much deeper sense, in the conventions of Byzantine music which form the basis of Orthodox church music.

Tavener initially tried to write exclusively for the Church, but felt too limited by the prospect of his pieces being heard only once in a Service. He tried to write using the Byzantine tone systems, but those raised in the idiom chided him for not really understanding them. Tavener researched in greater depth. "I toured Greece," he recalled, "noting down fragments; I read academic books with considerable boredom, on the eight tones on which Orthodox services are based."

Just as his new faith shaped his attitude to composing, so his acquired knowledge of the tone system changed his method. Centrally, he turned to the isom, or drone, in which melody weaves over a sustained chord (interestingly, he had spontaneously tried something similar in the Celtic Requiem).

His faith also transformed the mood of his music, making it more peaceful and transcendental. "I have sometimes been dubbed minimalist and namby-pamby New Age," he said, "which means to me an easy cop-out. There is nothing easy about achieving simplicity." It crystallised the meaning in his music towards ritual and symmetry, as is evident in Eis Thanaton (1986), and Mary of Egypt (1990-91).

From the 1980s he turned for his texts to Mother Thekla, Abbess of a tiny Orthodox monastery in Yorkshire. She shared his faith and penchant for simplicity, able to reduce the thematic issues to their bare essentials, "a kind of spiritual Agatha Christie," as Tavener put it.

Around this time he began to suffer the health problems which would plague him for the rest of his life. He had inherited Marfan's Syndrome, which can affect the connective tissue of very tall people (Tavener was 6ft 6in) – a condition he shared with Abraham Lincoln and Sergei Rachmaninov. He became suddenly more aware of his mortality and death became a preoccupation in his work – in Apocalypse (1993), for instance, which he sketched while awaiting open-heart surgery, unsure if he would ever awake again. In 2007 he had a heart attack, which necessitated bypass surgery and at one stage there were fears he had suffered brain damage. While he was unconscious he was played Mozart by his wife, who had flown to be at his side. He later recalled: "I apparently, in my unconscious state, began conducting. So that brought me round again."

At the turn of the 1990s The Protecting Veil, which he had written in 1987, leapt to the top of the classical charts and stayed there for months, inducting Tavener into the small band of living art composers with a broad audience, along with Henryk Gorecki, Arvo Part and, in quite a different style, Philip Glass, "When I saw that a lot of people were touched by The Protecting Veil I thought that I must continue doing this," he reflected. Yet, he mused, "I really don't know why it has been so successful when some of my other pieces haven't. In fact, I'm sick to death of hearing it."

From that point onwards Tavener's new works were given star treatment, and in 1993 he received the first Apollo Award from Greece (Tavener was "a Byzantine from London," the Greek press said), while Radio 3 ran a Tavener Festival in January 1994.

"In this last illness, when I came so near to death," Tavener noted in the early 1990s, "I realised that the only way was to live at all risks, otherwise there is no point in living at all." The "risk" he took was to marry again, to Marryanna Schaefer, and to have with her a first child, Theodora ("gift from God"), who was baptised at Mother Thekla's monastery. Two more children followed.

Tavener's standing in the cultural life not just of Britain but also of the wider world was sealed when his piece Song for Athene was used at the funeral of Princess Diana. Subsequently, his inspiration was derived from a wider range of philosophical sources – most notably expressed in the monumental Veil of the Temple (2003) – but also from great figures of western culture, such as Tolstoy, Mozart and, most recently, Beethoven.

Another of his compositions, A New Beginning, saw in the new century at the Millennium Dome in London, and he even twice featured in the shortlist for the Mercury Prize, lining up against chart stars and more esoteric performers. He was knighted for Services to Music in the Millennium Honours list of 2000.

The day before he died, he appeared on BBC Radio 4's Start the Week discussing music and prayer with host Andrew Marr and his fellow guest Jeanette Winterson, although the interview was recorded last month.

The world premiere of his work Three Shakespeare Sonnets is due to be performed by an Icelandic choir at Southwark Cathedral in south London on Friday.

John Kenneth Tavener, composer: born London 28 January 1944; Kt 2000; married firstly Victoria Marangopoulou (marriage dissolved), 1991 Maryanna Schaefer (one son, two daughters); died Child Okeford, Dorset 12 November 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments