John Houghton: Scientist whose work on the climate crisis influenced world leaders

He was chief editor of three studies by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and in 2007 shared the Nobel Peace Prize

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sir John Houghton was a Welsh atmospheric physicist who bridged the science, policy and religious communities and served as lead editor of groundbreaking studies for the United Nations’ climate science advisory group when it won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007.

Houghton, who has died of suspected complications from coronavirus aged 88, was among the most influential early leaders of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which was set up in 1988 to advise policymakers on the science of global climate change. He was the chief editor for the IPCC’s first three reports and chaired or co-chaired the panel’s scientific assessment committee.

The first IPCC report, released in 1990, helped spur world leaders to convene the Rio Earth Summit two years later. At that landmark gathering, virtually all nations committed to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), an ambitious treaty requiring countries to prevent “dangerous interference” with the global climate. Each round of annual UN climate negotiations since have taken place under the auspices of the UNFCCC.

The second IPCC report in 1995 informed negotiators of the Kyoto Protocol, an agreement that forced developed nations to commit to binding greenhouse gas emissions limits, while developing countries took other steps.

The third IPCC report, published in 2001, for the first time attributed “most of the observed warming over the last 50 years” to the human-caused build-up of greenhouse gases in the air. It also documented rising seas, melting glaciers and other signs of a rapidly warming planet.

In 2007 Houghton was among the IPCC scientists who collected the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo on behalf of the organisation, which shared the award that year with former US vice president Al Gore “for their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change”.

Houghton was also the director general and chief executive of the UK Meteorological Office from 1983 to 1991 and established the organisation’s Hadley Centre for Climate Science and Services, which is now one of the world’s foremost research bodies on climate science.

His work on climate research began in the 1960s when the focus, amid the Cold War, was on studying potential changes in the atmosphere in the event of nuclear fallout. At the University of Oxford, he conducted research into the temperature structure and composition of the atmosphere using Nasa’s Nimbus satellites.

By the 1980s, Houghton was on the vanguard of studying the alarming levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. He joined the nascent IPCC and tried to convince policymakers of the existential threat of climate change. “In our first IPCC report,” he told the South Wales Echo, “it became very clear to us that there was some real danger ahead, without being able to spell it out as clearly as we can now.”

His argument was scientific, but he imbued it with the moral imperative and obligation of his Christian faith. In particular, he expressed a deep concern for how the “grave and imminent danger” of the climate crisis would affect tens of millions of vulnerable people in developing nations. “As a Christian I feel we have a responsibility to love our neighbours,” he often said, “and that doesn’t just mean our neighbours next door. It means our poorer neighbours in the poorer parts of the world.”

John Theodore Houghton was born in Dyserth, Denbighshire, in 1931. At 16 he won a scholarship to Oxford, where he studied physics at Jesus College. He received a bachelor’s degree in 1951 and a doctorate in 1955 and went on to become a professor of atmospheric physics at Oxford.

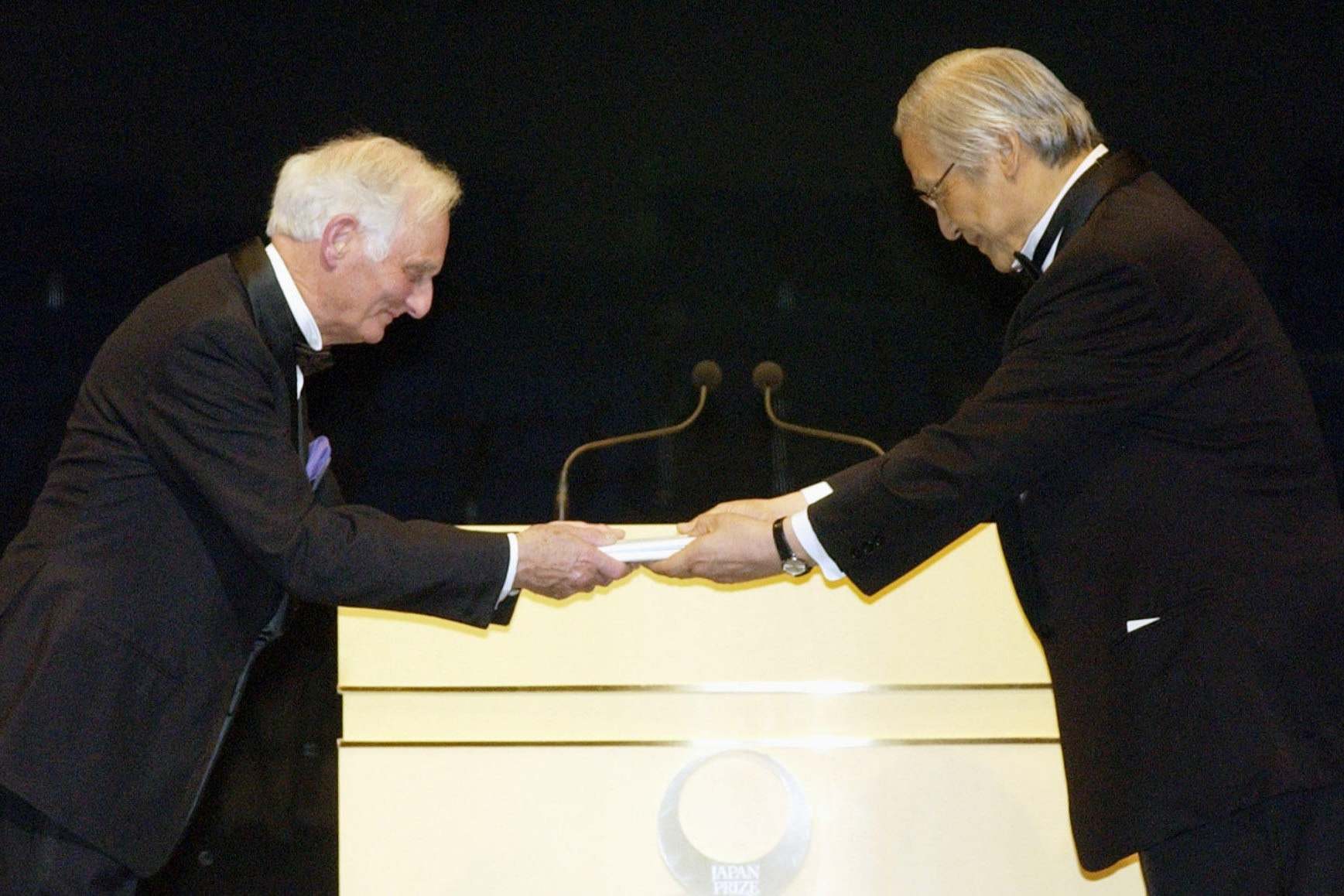

In 1972 Houghton was elected a fellow of the Royal Society. He was knighted in 1991, won the Royal Astronomical Society’s gold medal in 1995 and was honoured with the Japan Prize in 2006.

As the science on the climate crisis became clearer, Houghton’s warnings about its consequences grew more urgent. In 2003 he wrote that the climate crisis constituted “a weapon of mass destruction”.

Houghton wrote the book Global Warming: The Complete Briefing (1994), now in its fourth edition. He was the author of widely used atmospheric physics textbooks as well as two books on science and religion. He also published a memoir, In the Eye of the Storm (2013).

In 1997 Houghton helped to form the John Ray Initiative, an educational charity focused on the intersection of science, the environment and Christianity.

“I think it’s a very exciting thing to put scientific knowledge alongside religious beliefs,” he told the Western Mail in 2007. “The biggest thing that can ever happen to anybody is to get a relationship with the one who has created the universe … In the great scientific awakening of 300 years ago with people like Sir Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle and Sir Christopher Wren and others who used to meet and talk about science in that great time – they were nearly all Christians.”

His first wife, Margaret Portman, died in 1986. Two years later he married Sheila Thompson. She survives him along with two children from his first marriage.

John Houghton, climate scientist, born 30 December 1931, died 15 April 2020

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments