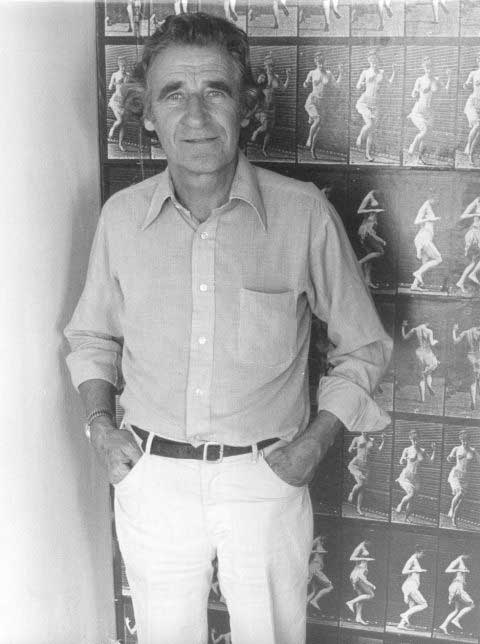

John Barnes: Authority on the early days of film who with his brother created an unparalleled cinema collection

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.John Barnes was a world authority on the archaeology and early history of cinema. The collection of books and artefacts which he formed over more than 70 years, in collaboration with his twin brother, William, could now never be paralleled in its extent and range.

The Barnes twins' passion for every aspect of cinema was born in traumatic circumstances. Their father, who was involved in the family business of the piano makers W.H. Barnes, died when the boys were 12 years old. A sympathetic uncle, seeing them marooned in a house of weeping grown-ups, gave the twins a 9.5mm projector to distract and console them. From that moment, they were possessed by film.

Soon, they had a camera and were spending their holidays making films about rural life in Kent and Cornwall, which are now appreciated as a precious documentary record. They seized upon every available book about the cinema. In 1936 they found and bought a tin box of films which turned out to date from the 1890s. At Canford School in Wimborne, Dorset, they established and ran a school cinema.

As teenagers, too, they discovered the Will Day Collection, then on loan to the Science Museum, which became a guide and model for their own future collecting. Day, who died in 1936, was an early film industry figure, with extraordinary foresight for the historical importance of the detritus of early cinema, who had collected omnivorously since the 1890s. "I cannot remember," wrote John Barnes,

the exact date when we first encountered the Will Day collection, but during the 1930s we often visited the Science Museum where we would spend many happy hours engrossed in studying the great collection which was displayed, or rather, shown, in rows of antiquated museum showcases. Drab it may have looked, but how

splendid the objects appeared, just placed there, without the intrusion of a designer's hand to distract the mind from the object of our gaze.

I do not think we were much aware of the man who had amassed these cinematic treasures. That came later. But his influence was already being infused unconsciously into our brain, so when finally we caught up with him, it was as if greeting an old friend, though, alas, we never met.

There were then no regular film schools, but in 1939 the brothers joined a course in film technique and design run by Edward Carrick, the art director son of Gordon Craig. The course took place in a studio in Soho Square, and, William Barnes recalls:

The premises were heated by a coal stove, and we had to go down to the cellar to bring up coal. The cellar belonged to an old antique dealer called Facciotto, and there among the coal we found this battered projector. We took it up and Mr Facciotto said we could have it for half-a-crown, so we bought it. . . Carrick was annoyed that he had not found it himself, and Facciotto said it was a mistake and that he wanted it back. But we kept it. It is a projector of 1897 patented by C. Stafford-Noble and F. Liddell, and is now the logo on our visiting card.

They had begun collecting at a perfect moment. After Day's death, here were no rival collectors of this disregarded stuff; and London's junk- and book-shops were virtually unmined. In Cecil Court was an antique shop with a cellar full of apparatus dating from the time when (long before Wardour Street) the court was the centre of the British film trade. In Bloomsbury Court was the bookshop of Andrew Block, piled to the ceiling with ephemera which he had been gathering and filing since 1910.

The war and service in the Royal Navy interrupted their activities, but on demobilisation the Barnes twins moved into a studio in St Ives which had been used by Whistler and subsequently by the twins' mother Garlick Barnes, a pupil of Sickert. Having already organised an exhibition of the collection in 1951 in the bookshop William had opened, in 1963 they opened Britain's first film museum in Fore Street, St Ives. The collection covered all the shows and science that had anticipated the cinema: peepshows, panoramas, shadows, magic lanterns, photography and chronophotography, as well as projectors and cameras from the first years of film.

The museum closed in 1986, leaving John free to devote himself to his research and writing. He wrote fundamental articles on cinema pre-history (many published in The New Magic Lantern Journal) and two volumes of a projected five-volume catalogue of the collection. His magnum opus, however, is Beginnings of the Cinema in England, 1894-1901, whose five volumes appeared between 1976 and 1998, by which time he had already enlarged and revised the first volume. Covering the technology, aesthetics, economics and exhibition of films, the books represent a range and depth of research made possible only by John's decades of study, collecting and first-hand knowledge of the films, machinery, documents and allied practices, like stage magic and music hall.

When there was neither enthusiasm nor funds in Britain to acquire the Will Day Collection, it passed in the 1950s to the Cinémathèque française in Paris, where it is worthily displayed. The Barnes brothers decided that they would not wish their own collection, either, to end up in a British national institution, having seen the cinema collections of the Science Museum, the Kodak Museum and the Royal Photographic Society swallowed up by the National Museum of Film and Photography in Bradford, where the great treasury of precious historical objects is relegated to the reserves (albeit visible by appointment) with only a pitiful sampling on display.

Hence, in the 1990s the Barnes' unparalleled collection of magic lanterns, slides and pre-cinematic optical devices and toys was acquired by the Museo Nazionale del Cinema of Turin, where it is now displayed in all its spectacular glory. That part of the collection which relates to the early years of cinema in Britain has been passed to the Hove Museum and Art Gallery – appropriately, since Brighton and Hove were a centre of Britain's first production.

In 1997 John and William Barnes were jointly awarded the prestigious Jean Mitry Prize by the Italian Giornate del Cinema Muto (the Pordenone Silent Film Festival) and in 2006 they received honorary doctorates from Stirling University. While John remained in St Ives, with his wife and collaborator Carmen de Uriarte, whose Spanish volatility admirably complemented his own characteristic pensive, smiling reserve, William stayed in London, where he is still one of the most dedicated and perceptive devotees of ephemera fairs, always the first to spot some unregarded treasure of pre-cinema history.

David Robinson

John Stuart Lloyd Barnes, film historian and collector: born London 28 June 1920; twice married (one son); died St Ives, Cornwall 1 June 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments