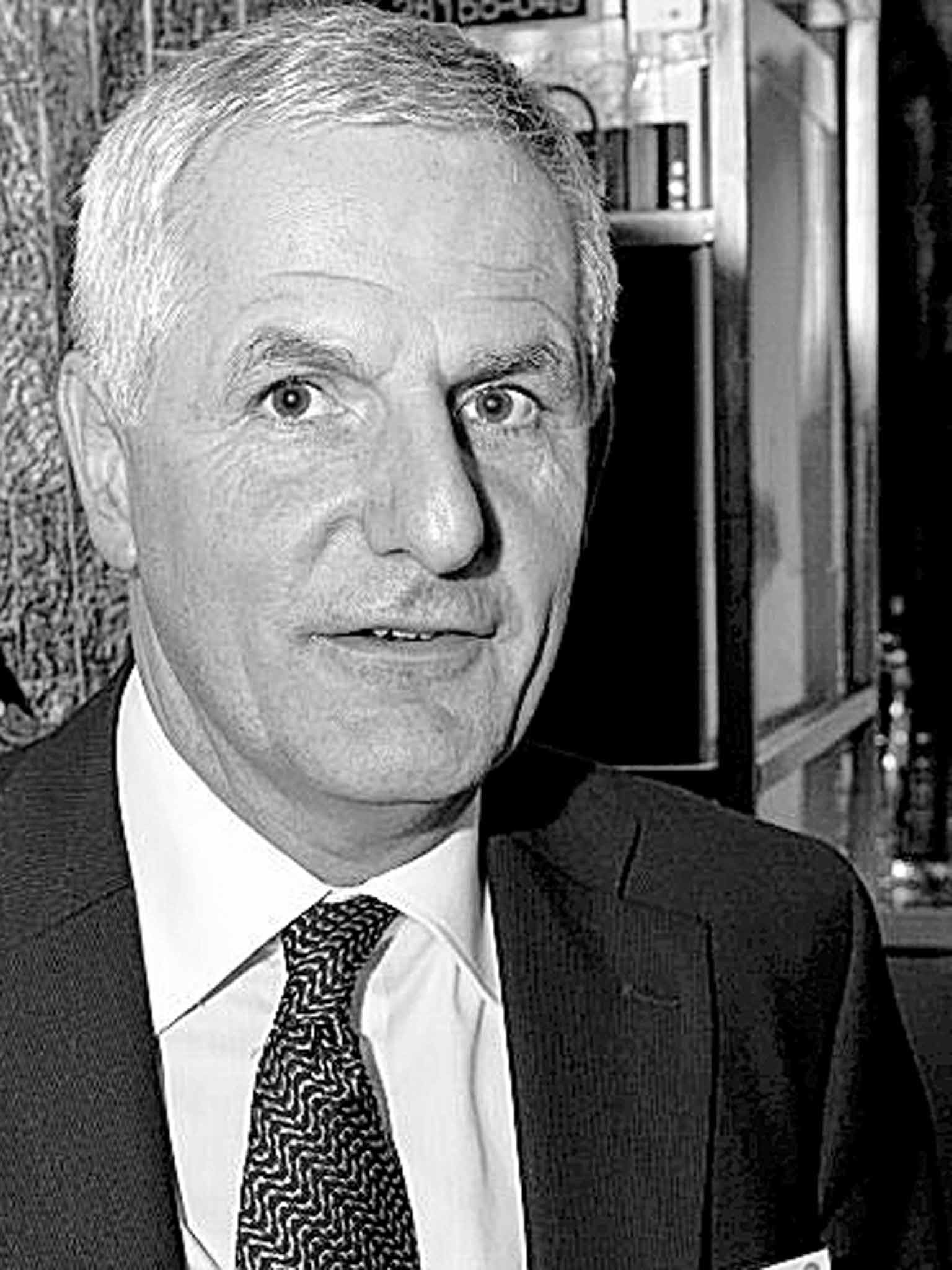

Joep Lange: Scientist and researcher in the forefront of the battle against HIV/Aids who was killed on Flight MH17

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Joep Lange was one of the many Aids researchers who died in Ukraine on Flight MH17, depriving the world of an invaluable store of expertise on the HIV virus. For decades he combined meticulous research, theoretical insights, international administration and academic work with an astonishing passion and determination to fight the disease.

Lange died with his partner, Jacqueline van Tongeren, as they were flying to Melbourne to attend a session of the International Aids Conference, which he once chaired. He was one of the heads of the Amsterdam Institute for Global Health and Development, while she was one of the Institute's communications directors. The Institute was one of an array of organisations with which he had been associated since 1980.

Lange was a native of Nieuwenhagen in the Netherlands; after receiving a doctorate in medicine from the University of Amsterdam he specialised in HIV/Aids. Part of his contribution was described by one of his mentors and friends, Dr Michael Merson, who said: "If you go back to the mid-'80s and early '90s, say the first 15 years of the pandemic, what you have now are a group of people in their 50s, 60s or even 70s. These were the people who fought so hard to get anything done – a new disease, you had people dying like crazy – and you built a kind of camaraderie."

He led early tests on the drug Retrovir, which proved to be the first breakthrough in Aids therapy, and went on to publish hundreds of scientific papers, one of which has been cited around 1,000 times and continues to be referred to today, 22 years after its publication. During the intervening years he took part in, and often led, many organisations and initiatives.

He worked on drug development at the World Health Organisation and edited the journal Antiviral Therapy. He was senior scientific adviser to Amsterdam's International Antiviral Therapy Evaluation Centre, helped supervise HIV research in Thailand and founded the non-profit PharmAccess Foundation, which is based in the Netherlands and has offices in Tanzania, Nigeria and other African countries.

The Foundation presses for the supply of vital drugs at affordable prices to deprived countries. One of his sayings was: "If we can get a cold can of Coke to any part of Africa, we can certainly deliver Aids treatment."

In the 1990s he became an advocate of combination therapy – using an array of drugs to treat HIV/Aids. It is this approach that more than any other succeeded in transforming a diagnosis of the disease from a death sentence to a question of management.

He was known for delivering stark warnings on the dangers of neglecting proper drug therapy. "South Africa, Botswana and Swaziland will be potential basket cases if they don't act," he once declared. "In the case of Botswana, if it doesn't act it will cease to exist."

In addition to dedicating so much of his life to his scientific work, he had passions for art, literature – he was a particular fan of the Portuguese Nobel laureate Jose Saramago – and conversation.

After the news of his death came through a colleague posted on Twitter of finding Lange, who was described as a doting father, taking part in conference calls on HIV while cooking for his five daughters. The colleague said, "I asked him why he worked so much. He said, 'Do you know how much it costs to buy shoes for five girls?'"

Many tributes were paid from various parts of the world. Richard Boyd, professor of immunology at Monash University in Melbourne, said, "He's one of the icons of the whole area of research. His loss is massive." Meanwhile Jeremy Farrar, Director of the London-based Wellcome Trust health charity, added: "He was a great clinical scientist. He was also a personal friend. He is a great loss to global health research."

Peter Piot, director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said: "He was one of the most creative Aids researchers, a humanist and tireless organiser, dedicated to his patients and to defeating Aids in the poorest countries."

Joseph Marie Albert Lange, scientist and researcher: born Nieuwenhagen, Netherlands 25 September 1954; partner to Jacqueline van Tongeren (five daughters); died near Hrabove, Ukraine 17 July 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments