Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Joao Havelange was president of Fifa, football’s world governing body, during a quarter-century in which the game allied itself to rampant commercialism in its quest to become truly global. The Brazilian sharply divided opinion over the course of a long career in which he also served on the International Olympic Committee from 1963 until 2011.

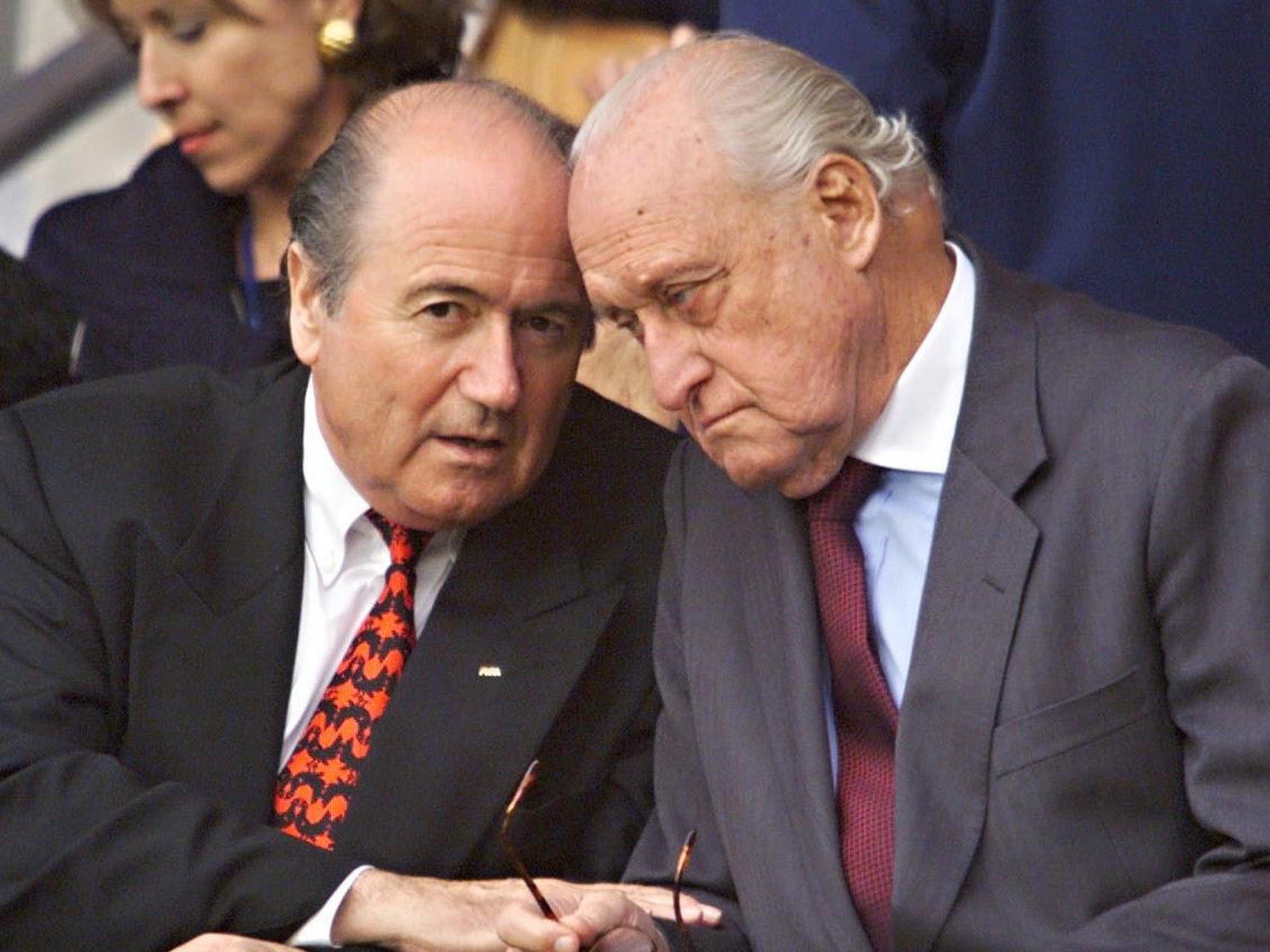

Havelange’s defenders viewed him as a statesman, who brought his sport, and the four-yearly extravaganza of the World Cup finals, into the modern age and funded its development in far-flung corners of the planet. Observing that football’s commercial potential had scarcely been tapped, he set about attracting sponsorship and creating television deals that gave Fifa and its corporate partners a grip on world football remains as tight as it is lucrative, despite the corruption scandal and arrests which overshadowed the re-election of his protégé, Sepp Blatter, as president in 2015.

To Havelange’s detractors, who ranged from Diego Maradona and Pele to the Panorama programme, he was the autocrat who sold football’s soul to Coca-Cola, McDonalds and other multinational corporations, turning the World Cup into a vehicle for making money.

He was also dogged by claims of financial chicanery, and in 2013 he resigned as honorary president of Fifa ahead of the publication of a report by its ethics committee which found he accepted “at least £1m” in bribes, conduct it described as “morally reproachable”. His former son-in-law, Ricardo Teixeira, who headed the Brazilian FA and sat on Fifa’s executive committee, had accepted £8.4m in backhanders.

Havelange was the son of Belgian expatriates who settled in Brazil after his father went to work there as a mining engineer. A tall, upright figure, he went to boarding school in France and, after becoming a wealthy lawyer and businessman in Rio de Janeiro, he competed as a swimmer in the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin as well as being part of Brazil’s water polo team at the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki. He was still taking a daily swim in his nineties.

In 1958, he became president of the CBD, the organisation which oversaw Brazilian sport, including football. He soon added the IOC to his portfolio, but being present at his country’s World Cup triumphs in 1958, ’62 and ’70 gave him an insight into the antiquated workings of Fifa and fuelled his ambition to take over and transform the organisation.

The 1966 World Cup in England had highlighted the competition’s outdated, Euro-centric format. North Korea filled the single place for Asia and Africa, alongside 10 European teams and five from South and Central America. To Fifa’s English president, Sir Stanley Rous, it would have been unthinkable to undertake the tour of nearly 90 Fifa member states, mainly from the Third World, on which Havelange embarked in what was effectively a presidential campaign in the four years leading up to the 1974 finals.

He wooed them with pledges of an expanded World Cup, in which 24 teams would contest the finals (the figure has since reached 32), and proposed tournaments at Under-20 and Under-17 level (later sold to JVC and Coca-Cola) to be held in developing countries. Rous, a conservative man born in Victorian times, appeared out of touch by comparison. Havelange won the election, becoming Fifa’s first non-European president.

To pay for the promised coaching schemes and facilities in the smaller countries which formed his new power base, Havelange looked to big business. The 1970 finals had been broadcast live and in colour around the world, pointing up the possibility for football to forge new markets for ever-hungry capitalism. Along with Horst Dassler, head of the German sports-goods manufacturer adidas, Havelange founded a marketing company, International Sports & Leisure, to sell TV and sponsorship rights on Fifa’s behalf.

Twenty years later, ISL collapsed amid charges of fraud, forgery and embezzlement against executives and owing creditors 450m euros. However, Havelange had already passed the presidential baton to Blatter, Fifa’s former secretary, after the 1998 World Cup in France, the sixth of his 24-year reign. No charges were brought against him.

He had been attacked for conferring legitimacy on Argentina’s military junta before the 1978 finals (although he was also lauded in Africa for opposing the admission of apartheid-era South Africa to Fifa, which Rous supported, and rated China’s return to Fifa after a 25-year exile his greatest achievement). He was criticised again for Fifa’s decision to award the 1994 tournament to the United States, a country with no national professional league at the time but arguably the perfect setting for the marriage of football and commercialism.

During those finals, Maradona was found guilty of taking a banned stimulant and expelled, after which the Argentinian described Havelange as “an inhuman robot”. Following Argentina’s defeat by West Germany in the 1990 World Cup final, he had refused to shake hands with Havelange when the president presented the medals, insisting that the match, decided by a dubious penalty, was fixed by the Fifa hierarchy. He later branded Havelange “a Mafioso” and accused him of “sipping champagne in the VIP box” while players toiled “in the midday heat” to satisfy TV contracts.

Relations with Pele were equally fractious. In 1973, two years after Brazil’s greatest player announced his international retirement, Havelange wrote to “My dear compatriot” asking him to reconsider. Pele resisted the invitation and antipathy continued to simmer.

In 1993 Pele accused Teixeira of corruption, alleging he accepted a $1m bribe to favour one TV deal over another. Havelange took revenge when the World Cup draw was made in Las Vegas; the fabled No 10, the great populariser of “soccer” in the US with New York Cosmos, was denied a place on-stage alongside such connoisseurs of the beautiful game as Faye Dunaway and Barry Manilow. The feud flared again in 1997 when Pele, as Minister for Sport, devised a plan to modernise football in Brazil. Havelange condemned “Pele’s Law”, with its dual aim of giving players greater freedom in choosing who to play for and making clubs more independent of the Brazilian FA.

When I arrived I found $20 in the kitty. When I departed I left property and contracts worth over $4bn

He summed up his patriarchal tenure at Fifa by saying: “When I arrived I found $20 in the kitty. When I departed I left property and contracts worth over $4bn.” In interviews he boasted that since the break-up of the Soviet Union, the world had just three major power blocs: the US, Fifa and the IOC.

Reluctant to see the presidency taken over by a candidate outside his confidants, the Swedish favourite Lennart Johansson, he broke protocol by campaigning for Blatter. Amid allegations of subsidised free trips for African delegates in return for votes, the succession proved seamless. Havelange became honorary president of Fifa.

In 2010 a Panorama programme, Fifa: Football’s Shame, accused him of accepting a $1m bung in 1997. Havelange did not rebut the claims (although the IOC, in stark contrast to Fifa, did pledge to investigate them). Asked in an interview later that year “what Fifa needed to do to change”, he replied: “Nothing. It’s perfect.” Months earlier, Blatter had been re-elected unopposed and Qatar astonishingly awarded the 2022 World Cup.

France gave Havelange the Cavalier of the Legion d’Honneur, one of 100 awards he received from countries and institutions. When the Olympics came to his home city of Rio in 2016, events were staged at the 47,000-capacity Estadio Olimpico Joao Havelange.

In 2011, the Brazilian Olympic Committee published a book titled Joao Havelange: The Greatest Sports Administrator of the 20th Century. It will sit alongside another by journalist David Yallop, the publication of which Havelange failed to prevent, called How They Stole The Game.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments