Joanna Richardson: Biographer and literary sleuth more interested in the flaws than the flourish of her subjects

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was the moment every biographer dreams of: going through the last box of photographs and, inside it (here the author takes over) "a small embossed red leather case which was fastened with a gilt clasp. One half was lined with magenta velvet, imprinted with a pattern of fuchsias. The other half held an ambrotype, brilliantly clear, in a gilt frame engraved with arabesques. It was the living likeness of Fanny Brawne."

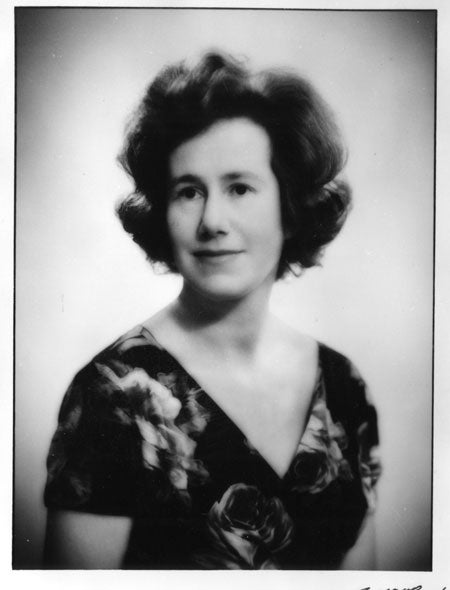

That was how the biographer and literary sleuth Joanna Richardson described her discovery in 1979 of an unknown and unique photograph of John Keats' great love. And it is typical of her style and method: patient attention to detail, a fascination with uncovering secrets, and the painstaking search for period authenticity. Between her first book, a biography of Fanny Brawne in 1952, and her last, a biography of Gustave Flaubert, unfinished at her death, she devoted her life to the search for a true picture of her subject and his or her times.

Born in 1925 to a cultivated Italianophile father and a strong-minded artistic mother, to whom she was very close, Joanna Richardson really came to life at Oxford University after the Second World War, where she read Modern Languages at St Anne's. Her degree – a third – was undistinguished, but she had found her twin loves, Oxford and France, and was able to combine them when she returned to Oxford in 1953 to do post-graduate research on Baudelaire under the buccaneering and sometimes brutal Enid Starkie. (Richardson was to write her biography in 1973).

It was not an easy or a happy relationship but, like fire on steel, it hardened and refined the ambition and literary skill of the younger woman. It also, perhaps, gave her a sense of vocation. In the introduction to her 1971 study of the French poet Paul Verlaine (Verlaine), she writes of her fascination with a man who could be both weak and vicious, who was physically repulsive, and yet could command warm affection and great loyalty: "One has only to read his letters, to catch the tone of his conversation, to understand his hold on his contemporaries. He is endearing and behind this disarming manner, one is suddenly aware of the presence of genius."

In other words, the biographer saw it as her mission to explore and explain what her friend and idol Isaiah Berlin called, quoting one of his heroes, "the crooked timber of humanity". The subjects she chose, apart perhaps from Keats, were complicated, difficult, often neurotic, and she was fascinated by the disreputable and bohemian lives that often lay behind the velvet curtains of the Victorian and Second Empire worlds in which she felt so at home: the lives of Théophile Gautier, Verlaine, Baudelaire, Emile Zola, 19th-century courtesans, Stendhal, and the astonishingly unconventional Judith Gautier (for whose biography she won a Prix Goncourt in 1989, the first time it had been awarded to an English writer). Even when she takes on national heroes like Victor Hugo (Victor Hugo, 1976) or Tennyson (The Pre-eminent Victorian: a study of Tennyson, 1962), Richardson is more interested in the flaws than in the flourish.

There was a downside to her relentless curiosity and exhaustive research. Too much detail, over-literal interpretation, and, sometimes, plodding narratives. She was not, on the whole, a good translator of French poetry, sticking too closely to the original, so that sharpness of image could be sacrificed to a cautious and clumsy fidelity. And her refusal to be defeated by difficulty or opposition could spill over into her personal relationships, leaving a number of bruised friends and new enemies behind her. Her period on the Council of the Royal Society of Literature, for example, was a contentious one, and neither she nor the society remembered each other with much affection.

What was never in question was Richardson's intellectual and emotional energy, which led her to campaign on local issues in north London – her beloved Keats House, for instance – and to write and broadcast for BBC Radio: I produced her spirited hymn to intellectual Oxford women for Radio 4 and a meticulously researched account of Flaubert's funeral for Radio 3.

She also contributed to magazines and newspapers, including The Times, the Times Literary Supplement, French Studies, the Modern Language Review and the Keats-Shelley Memorial Bulletin. France, to which she devoted so much of her time and talent, appointed her a Chevalier de L'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1987, and a framed photo of her receiving the 1989 Goncourt hung on the stairs of her charming 19th-century terrace house in Hampstead.

It was here, above all, that she showed her hospitality and wit, in spite of feuds with the local council and neighbours who had fallen out of favour. But her niece and nephew, her great-niece and great-nephew, local children, and long-term friends from Oxford and elsewhere, remember a demanding but ultimately warm and encouraging woman, who could see beyond her own political and social convictions – High Tory, royalist and élitist – to understand, if not embrace, their own very different attitudes and points of view. Even in the last few years, when sight and sound were fading and Parkinson's disease made movement difficult, she remained alert and curious, enjoying occasional trips to Oxford and the visits of friends, particularly if they could bring her some good gossip.

An earlier friend, the publisher Jock Murray – "the only publisher", in her words – had also been the only person who could get her to cut her work. "Ah! Joanna", he would say, astutely, "the echo of it will remain." As, I think, will the echo of Joanna Richardson, whenever 19th-century French and English literature are studied. In 2005 she was given a DLitt by Oxford University, a long overdue acknowledgement of her achievements.

Piers Plowright

Joanna Leah Richardson, biographer, translator and broadcaster: born London 8 August 1925; FRSL 1959; died London 7 March 2008.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments