Joan Didion: Revered writer who chronicled American culture

With an unwavering eye and a piercing intellect, Didion revealed an America gripped by moral decadence and self-deception

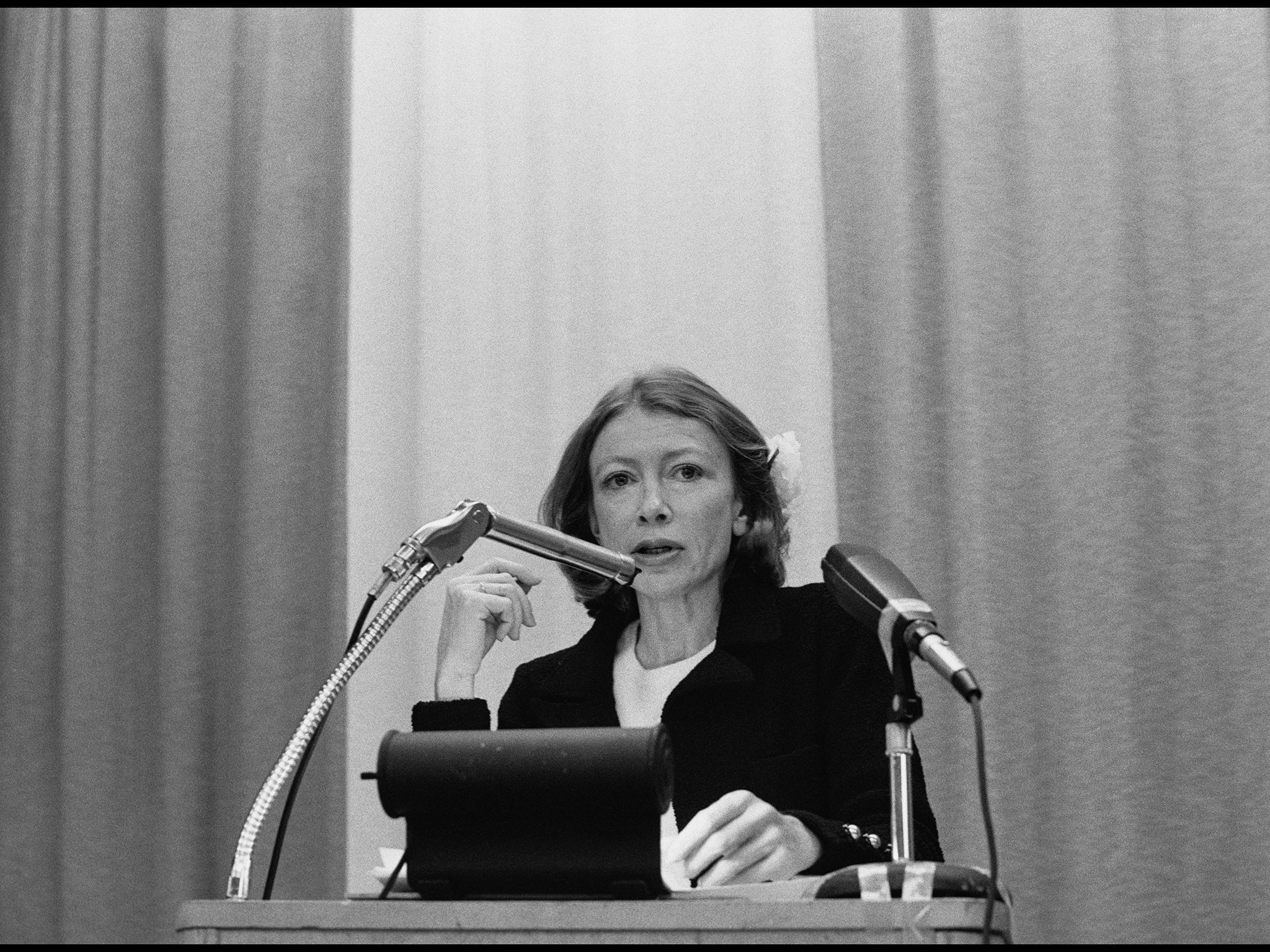

Joan Didion, a virtuosic prose stylist who for more than four decades explored the agitated, fractured state of the American psyche in her novels, essays, criticism and memoirs, and who as one of the “New Journalists” of the 1960s and 70s helped reportorial non-fiction acquire the status of an art form, has died aged 87.

With an unwavering eye and a piercing intellect, Didion revealed an America gripped by moral decadence and self-deception, its citizens in thrall to false narratives that offered little explanation of how the world worked.

Her trenchant, frequently contrarian opinions on subjects as varied as the films of Woody Allen and the traffic in Los Angeles were matched by a precise style that was almost universally admired.

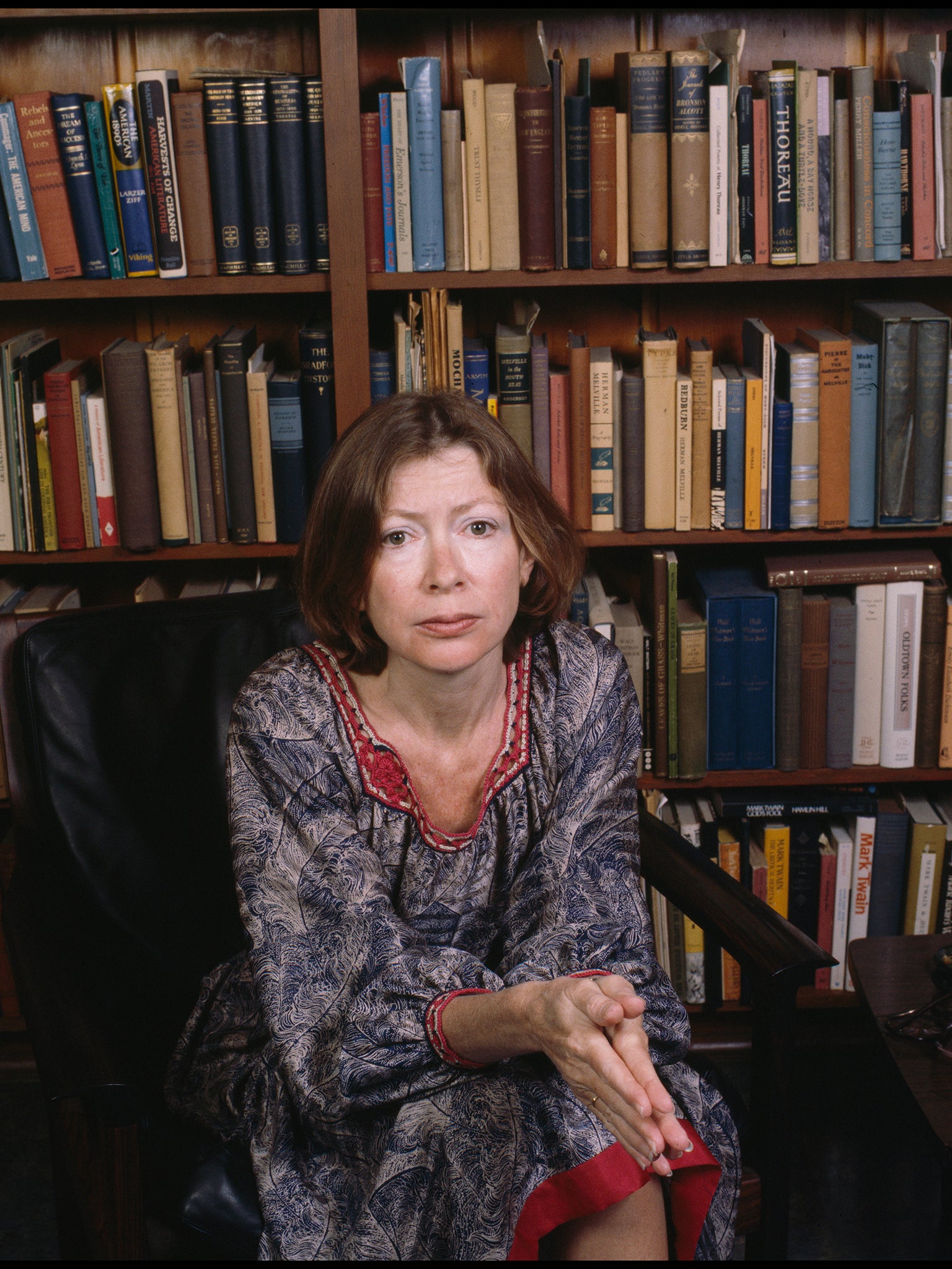

Many of her early works – the classic essay collections Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968) and The White Album (1979) – chronicled the grim realities of mid-century California. In that sun-dappled land of pleasure and possibility, America seemed instead to be falling apart, atomised by greed and amorality.

Didion argued “that the Norman Rockwell version of America was a convenient illusion, and that if you looked closely, we lived in a time in which fear and anxiety and isolation and loneliness were our common laws”, said Martin Kaplan, a professor of entertainment, media and society at the University of Southern California, in a 2015 interview.

In her later years, Didion became known for her dispassionate memoirs on death and grieving. In The Year of Magical Thinking (2005), she tracked the elliptical, death-denying patterns of thought that dominated her life after the sudden loss of her husband, John Gregory Dunne, from a heart attack at home, when he and Didion had just returned from visiting their daughter in hospital.

“Long before what I wrote began to be published,” Didion wrote at the book’s outset, “I developed a sense that meaning itself was resident in the rhythms of words and sentences and paragraphs, a technique for withholding whatever it was I thought or believed behind an increasingly impenetrable polish.” Yet, she continued, “this is a case in which I need more than words to find the meaning. This is a case in which I need whatever it is I think or believe to be penetrable, if only for myself.”

The book sold more than a million copies, won the National Book Award, and was adapted by Didion into a well-received Broadway play starring her friend Vanessa Redgrave. Its success was darkened by the death of Didion’s daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne, shortly after its publication.

Like Tom Wolfe and Truman Capote, Didion was one of the few writers of her era who were instantly recognisable to a mass audience through their cultivation of an off-the-page mystique. Photographed for Time magazine shortly after the publication of Slouching, she seemed a paragon of sang-froid, posing in front of her yellow Corvette Stingray with a cigarette in her hand.

She remained a fashion icon until late in life, photographed for a Céline ad in 2015 with her hair in a bob and her eyes obscured by a pair of large, dark sunglasses. Yet she also explored her physical fragility, writing about her frequent migraines, and revealing, in the title essay of The White Album, that she had gone blind for six weeks from a condition diagnosed as multiple sclerosis, and had checked herself into a psychiatric clinic.

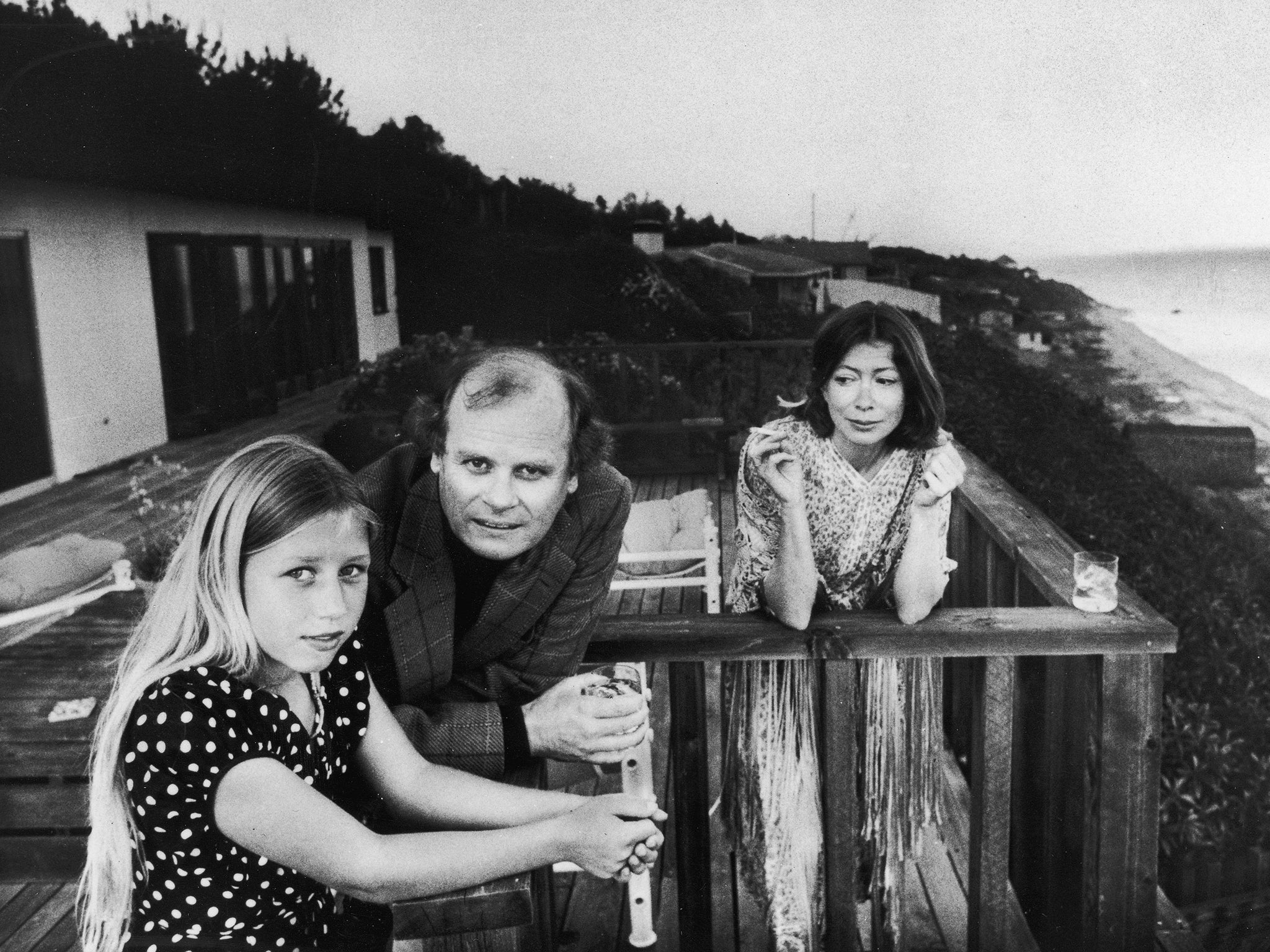

Didion and Dunne, a fellow novelist, largely funded their literary work by writing and revising Hollywood screenplays. Ensconced in the social whirl of 1970s Hollywood, the couple hosted and partied with stars including Warren Beatty and The Mamas and the Papas, and were among the most highly paid screenwriters in Hollywood.

Their films included A Star Is Born (1976), with Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson as rising and fading rock singers, respectively; and True Confessions (1981), featuring Robert De Niro and Robert Duvall in an adaptation of Dunne’s LA crime novel.

Didion herself was often disparaging of screenwriting, which she told The Paris Review was “not writing” but “notes for the director”.

The other writing she did, the “true” writing of her essays and books, was essential to her life. “Had I been blessed with even limited access to my own mind there would have been no reason to write,” she said in a talk and essay titled “Why I Write”. “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.”

Joan Didion was born on 5 December 1934, to a fourth-generation California family. Her father sold insurance and later became a real estate speculator; her mother, Didion later wrote, was a socialite who “‘gave teas’ the way other mothers breathed.”

Travelling across the country with her father, who worked as a finance officer with the Army Air Forces during the Second World War, she developed a nearly lifelong habit of taking her notebook with her wherever she went, furtively recording snatches of dialogue from adults whispering behind closed doors or convalescing at military hospitals.

Shortly before graduating from the University of California at Berkeley in 1956, Didion won a Vogue magazine contest for young writers. Choosing between the contest’s two prize options, a trip to Paris or a job at Vogue, she decided she would try her luck at the magazine’s offices in New York.

On the side, she wrote for publications including the National Review, The Nation and The Saturday Evening Post. Whether praising the work ethic of an ill and ageing John Wayne or, in later years, offering a scathing critique of Woody Allen and the “faux adults” in movies such as Manhattan and Interiors, she developed a reputation as an independent-minded critic, fiercely concerned with authenticity.

In 1964, she married Dunne, who was working as a staff writer at Time. They quickly left for Hollywood, where Dunne’s older brother, Dominick, worked as a movie producer and was able to introduce them to studio executives around town.

Rocked by alcohol and their shared ambition to be great writers, their marriage was tumultuous in its early years, a fact that Didion did not hesitate to incorporate into her work. When in 1969 she was given a regular column at Life, she began her first piece this way, describing a family trip to Hawaii: “We are here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce.” Dunne, as he always did, edited the story.

Their daughter, Quintana Roo, was born in 1966 and was soon adopted by Didion and her husband, who named her for a state in Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula. They returned to New York in 1988, taking an apartment on the Upper East Side, where Didion lived until her death.

A Barry Goldwater Republican for much of the 1960s, Didion gradually became disillusioned with the party during Ronald Reagan’s tenure as governor of California. Encouraged by Robert Silvers, editor of The New York Review of Books, she increasingly focused on the theatre, and on the hypocrisy of American politics, in non-fiction books such as Salvador (1983), about US involvement in El Salvador’s civil war, Miami (1987), about that city’s Cuban immigrant community, and the essay collection After Henry (1992).

The press was a frequent target in her work, with Washington Post journalist Bob Woodward taking some of her most biting criticism in a 1996 essay, included in her collection Political Fictions (2001), which described his reporting after Watergate as mere stenography for the nation’s political elite.

Her political work, as well as her more personal writing in books such as Where I Was From (2003), a blend of memoir and California history, was guided by a concern with “narrative”. Stories, in her view, allow us to make sense of our lives and world – though not infrequently these stories are myths; comforting fictions liable to crack.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Didion wrote in the title essay for The White Album. She added: “We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience. Or at least we do for a while.”

Joan Didion, journalist and author, born 5 December 1934, died 23 December 2021

© The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.