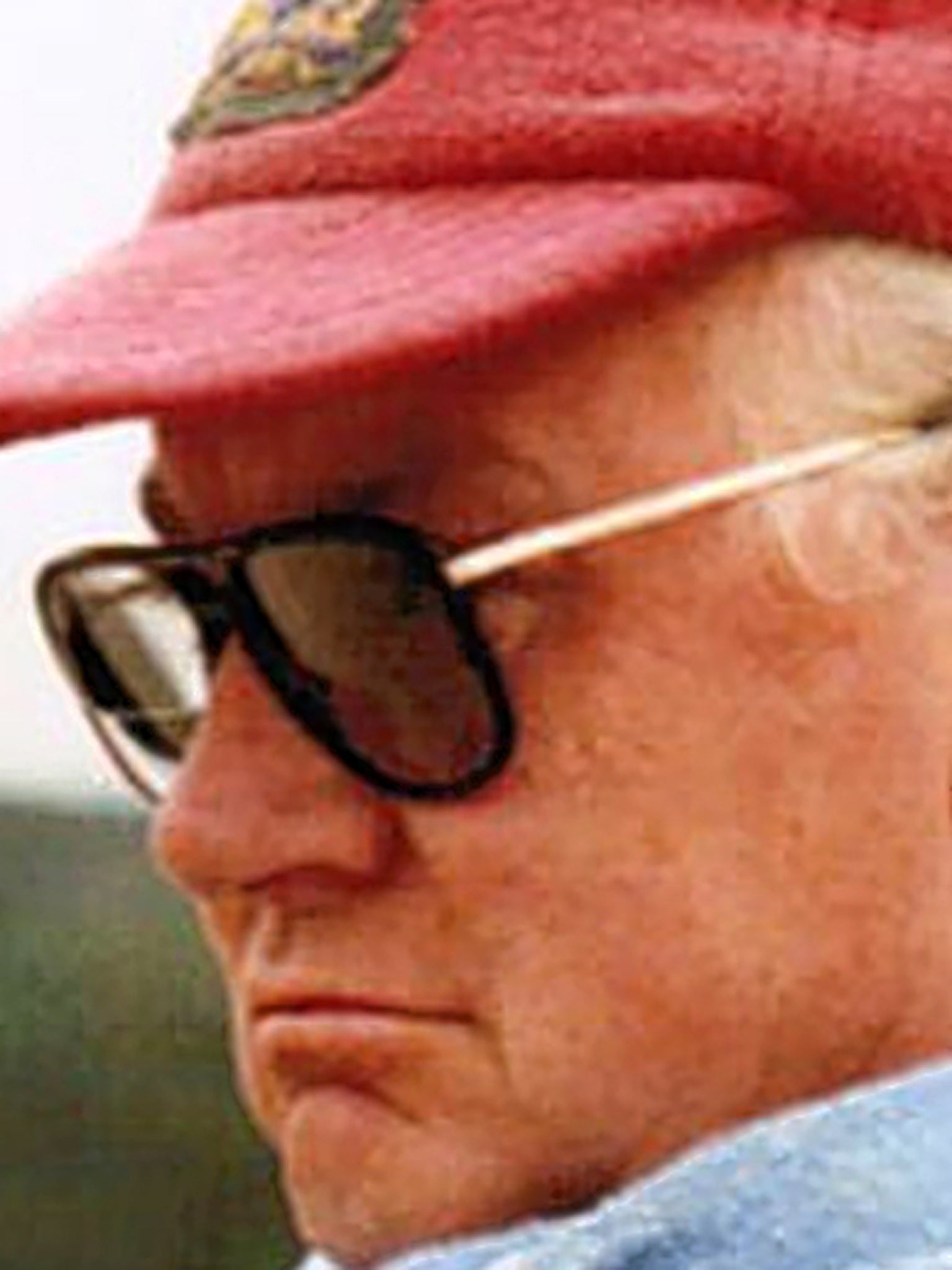

Jim Goddard: Director whose best work brought a grim, seedy beauty to London's underworld

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A master of tough film-making for the small screen, Jim Goddard excelled at the grittier, seedier end of crime drama. He worked exhaustively on both sides of the Atlantic, producing excellent work on everything from political thrillers to period dramas, but it was the London underworld that he did best. His background as an artist and designer brought a strange and seedy beauty to the mean streets he shot, and while he was no slouch at showing violence for what it is, Goddard's power was in complex characters, menacing moods, and in making monsters human.

His finest work was the six-part serial Out (1978), which depicted ex-con Frank Ross (the unsmiling Tom Bell in a Bafta-nominated performance) hunting for the villain who had grassed on him. Laced with author Trevor Preston's usual tough verisimilitude, and peopled with a rogue's gallery of lugubrious London actors, the serial remains one of the finest and least clichéd of British crime dramas. Goddard was fond of remembering that apparently when a rail strike scuppered many people's hopes of making it home in time for the final episode, "who grassed Frank Ross?" could be seen scrawled across blackboards at Euston station.

Born in Battersea in 1936, Jim Goddard studied at the Slade School of Fine Art, and then became a set designer, first for the Royal Opera House, and then from 1960 for ABC TV, where he could be working one week on a kitchen-sink drama and the next children's sci-fi. A show as unpredictable in its setting as The Avengers (1960-69) certainly kept him on his toes, but he soon had itchy feet, eager to try his hand at directing. He was given his chance on the excellent arts show Tempo (1965). Goddard delivered a gloriously entertaining piece on Orson Welles, and for an edition on Harold Pinter, he included scenes from Pinter's plays within the programme, allowing him for the first time to direct actors.

From there he directed the now forgotten Sat-day While Sunday (1967), a teatime teen drama which starred Timothy Dalton and Malcolm McDowell and which was scripted and narrated by the Mersey poet Roger McGough, whom Goddard struck up a lifelong friendship with. The first evidence of his mastery of crime came with an entry for ITV Playhouse entitled "Murder: Double Negative" (1969), and it led to work on many fine series of the day such as the chirpy Budgie (1971), the chilly Cold War thriller Callan (1970) and Public Eye, featuring Alfred Burke as the dour private ey Frank Marker (1968-73).

His first work for Euston Films, the new offshoot of Thames that made all film drama for ITV, was on The Sweeney. The episode "Trap" (1975) was one of the busiest and most intelligent of the series, as a Fleet Street newspaper is used as an instrument of revenge by a gang of recently released criminals intent on destroying Regan. Goddard's direction of the piece was striking, and the whole 50 minutes reeks of injustice and malevolence, not least when Brian Hall, with a face that looks like he is wearing a stocking over his head, batters Regan and Carter unconscious in a murky pub.

After Out Goddard directed another strong study of a family of villains, Fox (1980), again from the pen of Trevor Preston and starring Peter Vaughan and a young Ray Winstone. He was back with Euston Films again for the much-lauded Reilly – Ace of Spies (1983), by which time he'd also directed The Black Stuff (1980), a single play for the BBC about a group of luckless roadmen.

He insisted on a good period of rehearsal despite working on film, and his intense concentration and immaculate casting made Alan Bleasdale's excellent script a palpable and timely hit which resulted in the hugely celebrated series Boys from the Blackstuff two years later that laughed and cried at the state of the nation.

Despite his track record of successes, Goddard could be amusingly superstitious: on occasion he refused to cut his hair until a production wrapped. Anyone who bumped into him in 1983 could have been forgiven for thinking he'd joined a commune. In fact he was directing Kennedy

The Golden Globe and Bafta-winning mini-series starring Martin Sheen catapulted Goddard into the major league, but it was a short-lived glory as the film with which he chose to make his mark with internationally was the calamitous Shanghai Surprise (1986). Total codswallop not helped by a dire Madonna leading the proceedings and her then husband Sean Penn throwing strop after strop on set, the film was bad news both for Goddard and for George Harrison's usually sensible Hand Made Films.

While creatively Goddard soon bounced back with good work for television again, commercially he struggled. He worked steadily for the rest of his career, including episodes of Holby City, The Bill and EastEnders, but sadly by the 1990s there was less material available worthy of his talents. He turned in sound work on Inspector Morse (1989), The Ruth Rendell Mysteries (1996) and Screen Two (1988-92) but by the turn of the century the tides had truly turned in a television world that quite simply didn't deserve him anymore.

James Dudley Goddard, director, designer and painter: born London 2 February 1936; married Maddie Burdett-Coutts (one son); died London 17 June 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments