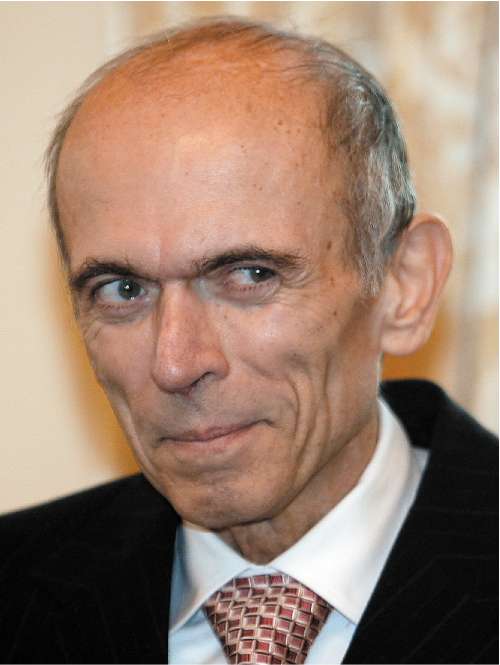

Janez Drnovsek: Slovenian president who achieved membership of the EU and Nato for the former Yugoslav republic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Janez Drnovsek emerged from almost complete obscurity to become Communist-ruled federal Yugoslavia's first (and last) directly elected president in 1989.

He could hardly have expected that just two years later he would be negotiating the withdrawal of the Yugoslav People's Army from his native Slovenia after its brief war of independence from the federation.

Another year on, Drnovsek took over as Slovenia's Prime Minister. With only a brief interruption, he held on to that post for a decade, as he guided his country's political and economic reconstruction. He successfully tackled the twin tasks of reorienting Slovenia's trade away from the wreckage of the old Yugoslavia towards the West and replacing the ineffective Communist-era business model with more market-based mechanisms.

Unlike the other five former Yugoslav republics which were run for much of the 1990s by charismatic and frequently authoritarian presidents, Slovenia under Drnovsek's premiership quickly emerged from the break-up of the federation as a functioning parliamentary democracy. Drnovsek concentrated on building coalitions, seeking consensus and making full use of Slovenia's technical expertise.

Drnovsek's Slovenia was unique in another important respect. While across most of the formerly Communist-ruled countries of Europe the economic and social transformation was orchestrated to the tune of full-blooded, neo-liberal policies – shock therapy and mass privatisation were the mantra of the day – Slovenia pursued a gradual, step-by-step approach. Instead of Thatcherism, Slovenia's model was Scandinavian-style social democracy and its variant, practised in neighbouring Austria.

By the time he stepped down as Prime Minister in 2002, Drnovsek had successfully negotiated Slovenia's membership of the European Union and Nato. Two years later came the crowning achievement of his political career when, as head of state, he presided over the celebrations to mark Slovenia becoming the first – and so far only – former Yugoslav republic to join these two organisations, which are viewed across the war-ravaged Balkans as the best guarantors of prosperity and security.

Born in 1950, Drnovsek graduated in economics in 1973, and then worked as a manager, a construction company executive and as an economics adviser at the Yugoslav embassy in Cairo. With no interest in a political career, he owed his selection as a member of the Slovene delegation to the part-time Yugoslav federal parliament to his much-needed expertise in monetary and credit policy. He seemed destined for a quiet life in the provinces.

All that changed overnight at the beginning of 1989 when Drnovsek's name was put forward – along with 74 others – for the post of Slovenia's representative on the collective Presidency of the Yugoslav federation. While most of those nominated declined to stand, he accepted the challenge, more out of curiosity than any realistic expectation that he could beat the political heavyweights favoured by Slovenia's Communist leadership. Normally, the successful candidate would have been picked by those same leaders behind closed doors. But with the process of democratisation already unstoppable in Slovenia, the most liberal of the Yugoslav republics, the decision was taken to hold a genuine election on the basis of universal suffrage.

To everyone's surprise, Drnovsek beat Marko Bulc, the official candidate, by a wide margin in the ballot in April 1989. Yet even after the election campaign, Drnovsek was still so little known that the taxi driver who took him home after his victory celebrations did not realise that he had been talking to the winner.

Drnovsek's success arose from the popularity of his clear message: his manifesto had called for a market economy and political democracy. However, that programme was not attractive to the seasoned Communist leaders whom Drnovsek joined on the Yugoslav Presidency, the body that brought together representatives of the six republics and two autonomous provinces that formed the federation. Drnovsek was not well prepared for the task that he was about to face. "I knew as much about what awaited me there", he recalled, "as I knew about what might await me on Mars."

Yet almost immediately the newcomer assumed the post of President of the Presidency – Yugoslavia's head of state – because it was Slovenia's turn to take the annually rotating chairmanship. For much of that year the Presidency was absorbed in dealing with the situation in Serbia's restive province of Kosovo, with its overwhelmingly ethnic Albanian population.

One of Drnovsek's main goals was to end the oppression in Kosovo which accompanied the abolition of the province's previously extensive autonomy as the President of Serbia, Slobodan Milosevic, imposed direct rule from Serbia. Yet for this, he had to undergo the most embarrassing occasion of his presidency, attending the huge gathering in 1989 to mark the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo – the Serbs' defeat at the hands of the Ottoman Turks – which a triumphant Milosevic turned into a nationalist rallying call for all Serbs.

However, his taking part in the celebrations improved Drnovsek's reputation among the Serbs, thereby helping him tackle the human rights abuses in Kosovo. Within a few weeks all Albanians interned without trial were set free. His step-by-step approach finally led to the lifting of the state of emergency in Kosovo at the end of his presidency. By then, the focus of attention had shifted to Slovenia and Croatia which were planning to hold multi-party elections in April 1990 for the first time since Communist rule was imposed. When the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) threatened to intervene, Drnovsek returned to Slovenia to cast his vote and visit polling stations, thereby publicly demonstrating his support, as head of state, for the return of democracy.

The victory of non-Communist parties in Slovenia and Croatia accelerated their estrangement from the rest of Yugoslavia, and they began to call for the transformation of the federation into a more loosely knit confederation. By contrast, Milosevic was determined to recentralise the country under his own leadership. After repeated attempts to reach a compromise failed, Slovenia and Croatia proclaimed their independence in June 1991. Almost immediately Slovenia's security forces took control of border-crossing points, and the JNA launched military operations to assert Yugoslavia's federal authority.

With his knowledge of the key players in the federal institutions and Serbia, Drnovsek became the linchpin in negotiations to end the conflict in Slovenia. His frequent discussions on the phone with Ante Markovic, the federal Prime Minister, and General Veljko Kadijevic, the Defence Minister, were virtually the only form of high-level communications between the two sides while the fighting lasted. When peace talks were arranged with the mediation of the European Community (as the EU was then known) on the Croatian island of Brioni, Drnovsek had the curious role of attending negotiations between Slovenia and the Yugoslav federation on the behalf of Slovenia while representing Yugoslavia in its talks with the Europeans.

The Brioni deal restored peace to Slovenia after a 10-day mini-war, but it imposed a three-month moratorium on independence and left the JNA forces deployed in the republic. However, Drnovsek had already picked up hints from Serb leaders that – notwithstanding their protestations of support for the Yugoslav federation – they would vote with him in the Presidency for the withdrawal of the JNA from Slovenia. He was aware that they wanted to prepare for the bigger battles ahead in Croatia and Bosnia, where the JNA would be needed to help the local Serb paramilitaries carve out Serb-run breakaway regions. Within days Drnovsek managed to strike a bargain with Belgrade, and the JNA left, allowing Slovenia to escape while the rest of Yugoslavia descended into even greater turmoil.

Slovenia's independence, which was eventually recognised internationally in January 1992, left Drnovsek without a job because there was no longer a place for him on the Yugoslav Presidency. Within months he was back in work – as independent Slovenia's second Prime Minister. Elected leader of the Liberal Democrats, the party that had emerged from the reformist youth movement of the late Communist era, Drnovsek was to be the dominant figure in Slovenian politics for the next decade. His mastery of intricate coalition politics was second to none. During that period he was out of power for only a few months – when one of his coalition partners left the government in 2000. He returned to office before the end of the year after winning another election.

Initially Drnovsek had to grapple with huge problems as his tiny, newly independent state, previously the workshop of Yugoslavia, had lost its traditional market, due to the boycotts and wars that accompanied the break-up of the federation. Slovenia needed to reorient its economic activities towards the rest of Europe, especially the EU. This required a transformation of the economy to boost productivity and efficiency through privatisation, the reconstruction of the banking system and the strengthening of the new currency, the tolar.

As an economist, Drnovsek was a hands-on Prime Minister who took control of key decisions. He was also well-served by his previous experience as a patient negotiatior on the Yugoslav Presidency because Slovenia's fragmented political environment made the formation and maintenance of each coalition government a tricky task. Politicians were also under pressure from trade unions and pensioners – whose party, Deus, joined the governing coalition at one stage – to protect the social welfare system during and after the transition to capitalism.

Drnovsek's centre-left governments pursued a more gradual programme of privatisation and liberalisation than its neighbours. Yet in spite of this cautious policy, Slovenia's economy bounced back and expanded by 50 per cent during Drnovsek's 10-year premiership.

Drnovsek stepped down from the post of Prime Minister in 2002, two years after he won his third and final election victory. With cancer, first diagnosed in 1999, showing signs of recurrence, he stood for election to the less demanding job of President. It was during his presidency, in 2004, that Slovenia achieved its twin foreign policy ambitions of joining the EU and Nato, which he had negotiated while he was still Prime Minister.

As his illness spread, gradually a new Drnovsek began to emerge. The conventional, even dull, politician was replaced by a prophet of New Age thinking. He moved to a mountain hut near the village of Zaplana where he grew organic vegetables and baked his own bread. Drnovsek became a vegan and said that his health improved greatly after he abandoned Western medicine in favour of herbal treatments and Eastern therapies. His Thoughts on Life and Awareness (2006), a guide to harmonious living, topped Slovenia's bestseller lists for a while.

As part of his new orientation, he left the Liberal Democrats and founded the Movement for Justice and Development to promote his projects. At his urging, Slovenian charities raised funds to help the victims of the humanitarian disaster in the Darfur region of Sudan. Impatient with the UN's half-hearted attempts halt the conflict, Drnovsek also worked hard at promoting a peace plan for Darfur, but it collapsed when the Sudanese authorities detained his personal envoy as a spy.

Drnovsek's activities exasperated Prime Minister Janez Jansa's centre-right government, which accused him of overstepping his powers by pursuing his own foreign policy, and refused to fund his initiatives. However, Slovenia's public continued to admire him, and he would have been easily re-elected for a second term, if illness had not forced him to retire from politics at the end of last year.

Gabriel Partos

Janez Drnovsek, politician: born Celje, Slovenia 17 May 1950; member, Presidency of the Yugoslav Federation 1989-91, President of the Presidency 1989-90; Prime Minister of Slovenia 1992-2000, 2000-02, President 2002-07; married (one son, one daughter); died Zaplana, Slovenia 23 February 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments