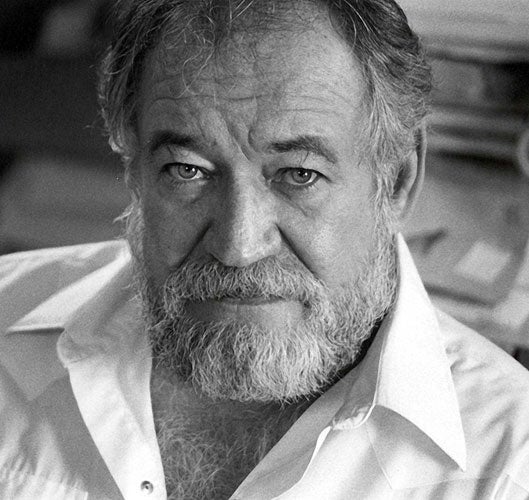

James Crumley: Crime writer whose low-life novels were infused with a rugged wit

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The hard-hitting crime writer James Crumley wrote novels of a honed, rugged wit that were narrated by investigators as down-at-heel as their quarries. In this he was an heir to Raymond Chandler, whose paperbacks he had come across in 1967, in a Mexican supermarket. It was an epiphany that made Crumley realise that sustained linguistic flourish was not solely the province of such work as his own first, sprawling novel about army life, One to Count Cadence. Seven more novels followed, the best of which were set in Montana, the patch he made his own throughout a turbulent, much-married life.

James Arthur Crumley was born in 1939 in a small Texan town, Three Rivers, that was dominated by an oilfield where his father, Arthur, was a supervisor; his mother, Ruby, was a waitress. Clever but wayward, often ill at ease, Crumley sought a fresh start with a naval scholarship to the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1957; but an apparent propensity to seasickness soon put paid to that and, bruised by academia, he joined the army. After three years mostly in the Philippines, he holed up at the Texas Arts and Industries University before studying creative writing in Iowa with Richard Yates. Briefly-held university jobs took him from Montana through Arkansas, Colorado, Texas and Oregon.

Along the way came One to Count Cadence (written after he left the army, and eventually published in 1969), which is in the form of a journal kept by "Slag" Krummel – perhaps a variant on Crumley's own name – while recovering from a wound. It recalls an edgy relationship with a fellow soldier, Joe Morning: each has more in common with the other than he would like to admit, and this dynamic fosters blistering prose. Extracts can only suggest its bravura and wit: "I still confused being a soldier with being a warrior"; to kill a bear is simply "what he would do to you, though with more animal reason and less waste". Elsewhere comes the observation that "dawn is one thing, daylight another: I had several drinks during the difference".

That sentiment could easily fit in any of his subsequent novels. The poet Richard Hugo had once said to him, "Goddamnit, I wish I could write like Raymond Chandler"; Crumley had sneered, and Hugo gave him "a look like Sidney Greenstreet would have admired". Duly converted on a Mexican holiday while floundering with a second novel, Crumley abandoned teaching. "To learn to write to live" meant rewriting "like a mad monk".

The Wrong Case (1975) resulted, with the investigator Milo Milodragovitch, whose history was as troubled as that of C.W. Sughre, who first appeared in 1978's The Last Good Kiss (a phrase from Richard Hugo's haunting poem "Degrees of Gray at Philipsburg"). Some found Crumley's two narrators difficult to tell apart (he even brought them together for alternate sections of Bordersnakes, 1996). Though these two novels are his best, he could always produce lines like: "Sheba Peak rises grandly, holding snow until the heat of summer, as white and conical as the breast of a young woman, a woman conceived in the tired dreams of a dirty miner, a dream only gold or silver might buy".

Crumley became a cult figure, some fans "even calling collect in the middle of the night – I never get tired of that part". Two decades before his kidneys rebelled at 68 he remarked: "I suspect I also refuse to live a life that, even though I know the ending, has a plot that isn't constantly changing as I live it." But a fifth marriage, to the poet Martha Elizabeth, brought happiness despite severe illness, when, as a preface to The Right Madness (2005) notes, she "stood next to my bed and never gave up. Even when I made a drugged pass at her, when I didn't know who she was".

Christopher Hawtree

James Arthur Crumley, writer: born Three Rivers, Texas 12 October 1939; five times married (three sons, two daughters); died Missoula, Montana 17 September 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments