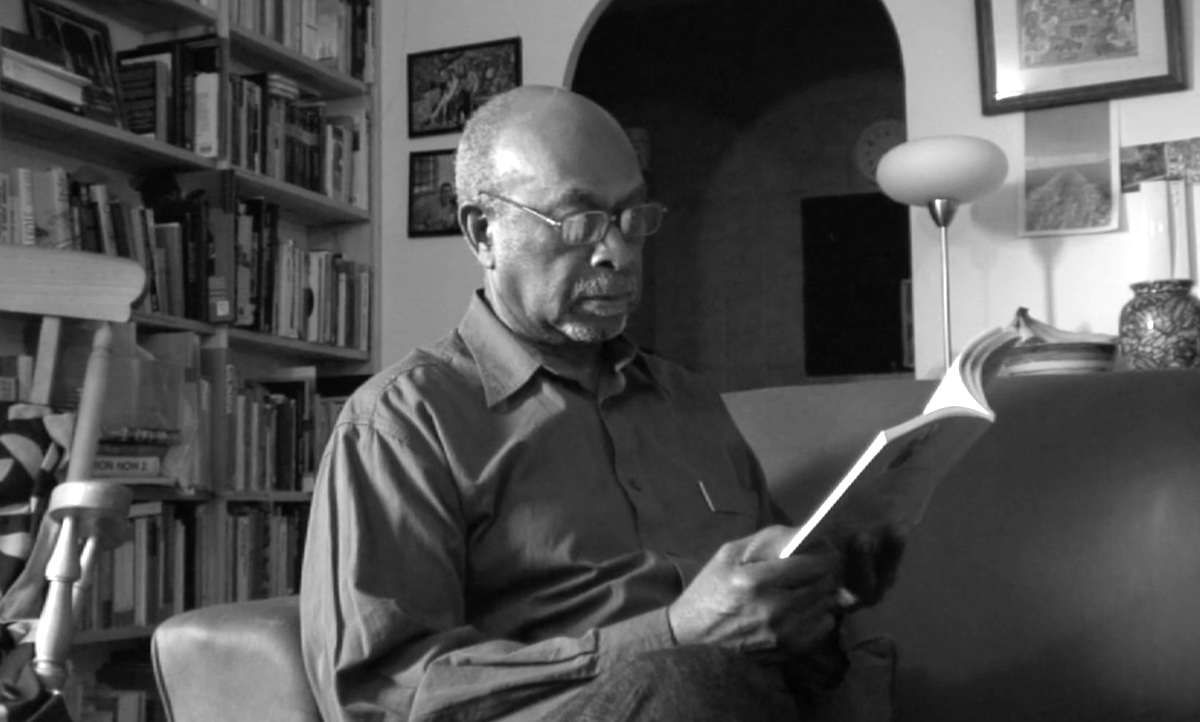

James Berry: Jamaican-British poet who introduced Creole into the canon

The writer, who spoke for the first-generation exiles, also championed his community’s verse

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1948, many young Jamaican men found themselves destitute and looking for a better life. And so they left, initiating the biggest movement of people yet from the Caribbean to Britain.

Among them was James Berry. Of the rut he and his generation sought to escape, he later wrote: “Here we were, hating the place we loved, because it was on the verge of choking us to death.” His first night in London he spent, unpromisingly, in a Salvation Army hostel.

These mixed emotions – a love-hate relationship with his childhood home, along with the hope of a new life in a foreign, at times unforgiving, land – would come to inspire much of his poetry, establishing him as one of the most prominent black voices in contemporary British literature.

Born the fourth of six children in the small coastal village of Fair Prospect in Jamaica, Berry learned to read before he had turned four. From a very young age he was exposed to two distinct tongues: on the one hand, the “standard” English of the Bible and of Sunday prayer books; on the other, the tunes of everyday Jamaican. Both voices would permeate his work.

Having left school at 14, Berry went through several small jobs, as a shoemaker, a tailor and a travelling medicine salesman. Aged 17, he went to the United States to work as a farm labourer. But he loathed the treatment of black people he observed in New Orleans, and returned home within four years.

Two years later, in 1948, he left Jamaica once again – this time for good. He boarded the SS Orbita, which was transporting the second group of post-war immigrants from the West Indies to Britain, following the SS Empire Windrush earlier that year. On the ship, he came into contact for the first time with people from all over the Caribbean, and felt a camaraderie toward them.

Upon arrival he soon got a job as a Post Office telegraph operator – a position he held for more than two decades. Simultaneously he wrote poetry, and started meeting some of the writers who had founded London’s Caribbean Artists Movement in the 1960s.

He himself formed a poetry performing troupe in 1972, the Bluefoot Travellers, making his own the term “bluefoot”, a pejorative Creole word for “outsider”.

His first book of verse, Fractured Circles, he published at the age of 54. One of its poems, titled “Outsider”, lay down his statement of purpose as an author:

If you see me lost…

it’s that I moved

my circle from ruins

and I search to remake it whole.

Much of his poetry explored how to rebuild a sense of self and belonging in an at-first unfamiliar place.

Having ended his career as a telegraphist in 1977 – the happiest day of his life – Berry was free to dedicate himself to writing. He published another four collections of verse, as well as a dozen books for children.

Berry did much experimentation with form, writing folk proverbs, rap lyrics, conversations, haikus and, in a series of poems that particularly suited him, fictional correspondence.

But what distinguished him was his ability to write beautifully both in “standard” English and in Creole, choosing one or the other, or sometimes interweaving the two in a single text. This style of his, he said, “simply emerged naturally”. But it was of great significance to Caribbean writers of his generation and the next, as it further legitimated Creole as a form of poetic expression. In one such poem, evoking the urge to set sail for Britain, Berry wrote:

To travel this ship, man

I woulda hurt, I woulda cheat or lie,

I strip mi yard, mi friend and cousin-them

To get this yah ship ride.

His attachment to oral patois placed him in the tradition of Claude McKay, the first Jamaican poet to defend the validity of Caribbean dialects in his 1912 poetry collection Songs of Jamaica. It also separated Berry from contemporaneous Caribbean poet Derek Walcott, who died earlier this year, and whose writing was in closer dialogue with the canonical English tradition, at least formally.

Berry edited two important anthologies of black British poetry – Bluefoot Travellers and News for Babylon – which served to publicise an otherwise little known literary movement that had developed with the arrival in Britain of young talents from the Caribbean. “Descendants of the silent labour force of old empire speak,” Berry wrote, with pride, of the poets whose work he had compiled. “They show themselves loaded with talk, with a compulsive confidence and a fresh history.”

Asking himself what unified West Indian-British poetry in the preface to News for Babylon, he answered that it was “a collective psyche laden with anguish and rage”.

Though he by and large felt welcome in Britain, a country he lived in until he died, he too experienced anguish and rage at the discrimination he sometimes encountered. In a poem about a racist dialogue he overheard on the London Underground, he concludes with the verses:

An aching hatred left the train

with me. All day suspicion

spurred me. I spoke hastily.

Retaliation wrestled me.

But Berry never gave up on the idea that people could feel empathy toward one another, and that poetry could speak to any reader, whatever their skin colour. Nor did he write only about the immigrant experience: his work could also be humorous and celebratory.

He was eager to pass his love of poetry on to the next generation, often doing workshops with schoolchildren, who he said inspired his writing. Some of his most touching poems – “When I Dance”, “One”, “What To Do With A Variation?” and “Isn’t My Name Magical?” – he wrote for children.

Berry is survived by his partner Myra Barrs. As for his archive of poetry notebooks, diaries and other material, it was purchased by the British Library in 2012.

Into his waning years, the Jamaica he’d left behind still was close to his heart. In a late poem, he wrote of being transported back to the land of his youth by the sight of a basketful of eggs:

I blinked, I saw: a trayful

of ripe naseberries, nesting.

I blinked, I saw: an open bagful

of ripe mangoes, nesting.

I blinked, I saw:

a mighty nest full of stars.

James Berry, poet, born 28 September 1924, died 20 June 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments