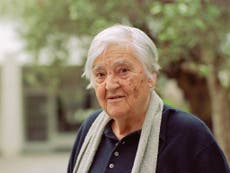

Jakucho Setouchi: Outspoken Buddhist nun who penned hundreds of books

Drawing on her own tumultuous love life, Setouchi became one of Japan’s most prolific novelists

“The most important thing to write about in novels is love affairs,” Jakucho Setouchi once said. “Corporations and politics – none of that is interesting.”

Setouchi, who has died aged 99, was one of Japan’s most popular and prolific novelists, drawing on her own tumultuous love life in more than 400 books about romance, sex, motherhood and family. Her protagonists were free-spirited women who, much like their creator, bristled at sexual mores and traditional gender roles, refusing to fade into the background of their homes while living in “a man’s society”, as Setouchi called contemporary Japan.

Her frank descriptions of sex and romance earned her a devoted following in the country, and were all the more striking given that Setouchi became a Buddhist monk at the age of 51, shaving her head, donning monastic robes and taking a vow of celibacy. For decades, she delivered sermons and spiritual talks while continuing to write in longhand with a fountain pen, publishing books that including a best-selling translation of The Tale of Genji, one of Japan’s most celebrated novels.

“Usually people who do bad things make good writers,” she said in a 2008 lecture. “I did a lot of bad things, which is why my novels are interesting.”

A homemaker turned author, Setouchi scandalised her family when she abandoned her husband and their daughter for a relationship with a much younger man. She later had an eight-year affair with a married writer, and shook up Japan’s literary world with a 1957 novel about a young woman who leaves her family and turns to prostitution.

The book – its title, Kashin, is variously translated as Pistil and Stamen, The Core of a Flower and A Flower Aflame – was dismissed as pornography by some critics who objected to her sexual imagery and the use of the word “womb”. At the novel’s end, the main character imagines that even after her death and cremation, her womb will survive intact. Setouchi acquired a derisive nickname, Womb Writer, and went on the offensive.

“I should have stayed quiet,” she later told The Japan Times, an English-language daily, “but I was so upset and responded to that criticism, saying, ‘Those who criticise the novel should be impotent and their wives should be frigid.’ Because of that remark, all the literary magazines refused to publish my novels for five years.”

By the end of that period, Setouchi had published one of her most acclaimed books, The End of Summer, a semi-autobiographical novel that won a women’s literary honour in Japan and was based on her own tangled relationships with her ex-boyfriend, her lover and his wife.

For all her writing about contemporary women and society, Setouchi was perhaps best known for her 1998 translation of a 1,000-year-old classic, The Tale of Genji. Written by Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting at the imperial court, the book chronicled the romantic life of the emperor’s son Hikaru Genji, “the Shining Prince”, who seduces a host of women, including his stepmother and adopted daughter.

The book’s plot was “hot stuff”, Setouchi noted in an interview with the New York Times. “Why pretend it’s the height of culture?” she asked. “People hear Genji and immediately they talk in whispers, like in a museum. Hah, ridiculous! Genji should be read on a sofa, with a box of cookies in hand.”

Written in an archaic brand of ancient Japanese, the original Genji is largely indecipherable to modern readers. Setouchi sought to translate the book “into plain, no-nonsense language”, trimming some of its longer sentences and producing a 10-volume version that sold several million copies and helped spark new interest in the novel.

“When a man and a woman are in love, the situation hasn’t changed in the last thousand years,” she told the New York Times in 1999. “There’s jealousy. There’s agony. Even a modern career woman can feel those same pains of love. So, yes, Tales of Genji is relevant to today’s people. And after all, it teaches the basics of love. And that’s very useful, isn't it?”

Setouchi was born Harumi Mitani in Tokushima, on the island of Shikoku in southwestern Japan, on 15 May 1922. Her mother was a homemaker, and her father was a cabinetmaker and craftsman who made religious objects for Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. He was adopted by a wealthy relative and took her surname, Setouchi, for his own family.

Setouchi was studying Japanese literature at Tokyo Woman’s Christian University when she married Yasushi Sakai, a scholar and schoolteacher, by arrangement in 1943. They had a daughter and lived in Beijing at the close of the Second World War. Her mother and grandmother were killed in US bombings back home in Japan.

While living in China, Setouchi started the affair that ended her marriage. She realised that her husband “had different values from me”, she told The Japan Times, but was never sure of the precise origins of the romance, or of any other love affair. “You don’t know when it’s coming and you can’t avoid it,” she said, “even though you may get injured or die.”

Returning to Japan, she worked at a publishing house and hospital in Kyoto before writing novels for young women and then adults. Her books came to include biographical novels about the lives of trailblazing Japanese women, including author Toshiko Tamura and social critic Noe Ito, although her own life felt increasingly “empty”, she told Agence France-Presse.

Deciding that she “wanted to pursue something else,” she became a Buddhist nun in 1973 and adopted the given name Jakucho, although she later lamented that she took her vows too early. “I had no idea I was going to live so long,” she said. “I thought it would be 25 years at most.”

Rather than retreat from daily life at her temple in Kyoto, Setouchi became a prominent antiwar activist, protesting against the Gulf War in 1991 and the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. She also campaigned against capital punishment, corresponding with inmates on death row in Japan. After a 2011 earthquake and tsunami triggered a nuclear disaster at the Fukushima power plant, she joined a hunger strike and called for an end to nuclear power.

She received Japan’s Order of Culture in 2006, during a ceremony at the Imperial Palace. A decade later, she helped launch the Little Women Project, a nonprofit organisation that supports girls and young women struggling with poverty, sexual assault, drug addiction and other traumas. She published her last full-length novel, Life, in 2017.

Her death, at a hospital in Kyoto, was announced on her Instagram account; at the age of 99, she was still posting selfies and writing updates to an audience of nearly 300,000 followers. The Associated Press reported that she died of a heart ailment.

Information on survivors was not immediately available.

Setouchi described her Genji translation as her “life project”, but said she initially struggled to connect with the book’s female characters, who were alternately romanced and discarded by the young prince. She developed a new view on the story during a fresh reading, when she was struck by the fact that many of the women became nuns.

“For them,” she said, “nunhood was a declaration of independence.” Setouchi seemed to feel similarly about her own immersion in the faith, telling the New York Times that as a Buddhist, “I cry and laugh like anyone else but at the same time I’m detached. Like none of anything matters, and I’m not here at all. This is freedom you know, real freedom. I suppose that’s what Genji’s women wanted, too.”

Jakucho Setouchi, writer and activist, born 15 May 1922, died 9 November 2021

© Washington Post