Jake LaMotta: world middleweight boxing champion and 'Raging Bull'

He was one of the toughest in the field, but was haunted by his own violence

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.While Jake LaMotta, the former world middleweight champion, is unlikely to be remembered as the most sophisticated exponent of the noble art, his claim to be one of its toughest practitioners can never be doubted.

In a 106-bout professional career which ran from 1941 till 1954, LaMotta took on some of the most respected fighters of his era, including the legendary “Sugar” Ray Robinson (whom he fought six times), Fritzie Zivic and Marcel Cerdan. In the process, LaMotta demonstrated an ability – even a willingness – to absorb punishment that seemed at times to border on the certifiably masochistic. As he later put it: “Subconsciously – I didn’t know it then, I realise it today when I know a little bit more about the mind and the brain – I fought like I didn’t deserve to live.”

LaMotta was born in the Lower East Side of New York in 1921, one of five children of a Sicilian immigrant father and an Italian-American mother. Apart from a brief spell in Philadelphia, the family was raised in the Bronx, where LaMotta senior eked out a living as a street peddler. By LaMotta’s own account, his father was a vicious man whose advice on self-preservation involved thrusting an ice-pick into his son’s hands with the words, “Here, you son of a bitch, you don’t run away from nobody no more! Hit ’em first, and hit ’em hard.”

It was a lesson LaMotta was to remember well, both as a young street thug and later as a fighter. One night, he followed a local street bookie onto a deserted lot and beat him savagely with a lead pipe; the next day he read of the man’s death in the papers. This incident was to haunt LaMotta for most of his career: “I never went to church, the priests couldn’t scare me with all that crap about hell, but somehow I knew, inside of me somehow I knew that I’d pay for it.”

Before long, LaMotta was caught attempting to break into a jewellery shop and was sent to the State Reform School at Coxsackie in upstate New York, where he renewed his friendship with one Rocco Barbella, better known as future fellow middleweight champion Rocky Graziano. Recalling their childhood, and LaMotta’s already violent disposition, Graziano once quipped: “Me and Jake LaMotta grew up in the same neighbourhood. You wanna know how popular Jake was? When we played hide and seek, nobody ever looked for LaMotta.”

It was at Coxsackie that both LaMotta and Graziano decided to become boxers. On his release, LaMotta began training at the Teasdale Athletic Club in the Bronx. He soon won the newspaper-sponsored Diamond Belt in the light-heavyweight division, before turning professional in 1941. Exempt from military service due to a childhood ear infection, LaMotta had 22 fights in his first year in the paid ranks. Although a natural light-heavyweight, he opted to campaign in the more prestigious (and better-paid) middleweight division.

With his large head, short neck and heavy shoulders, LaMotta was soon dubbed the “Bronx Bull”, and his all-action style and apparent disregard for seIf-defence soon made him a popular draw at the many venues in which he fought. However, it was his ferocious performances in losing fights (against the more experienced Jimmy Reeves and Nate Bolden) that helped make his reputation, with one reporter writing of the Reeves bout, “Had the fight been held in an alley there isn’t any doubt in my mind which man would have been the winner.”

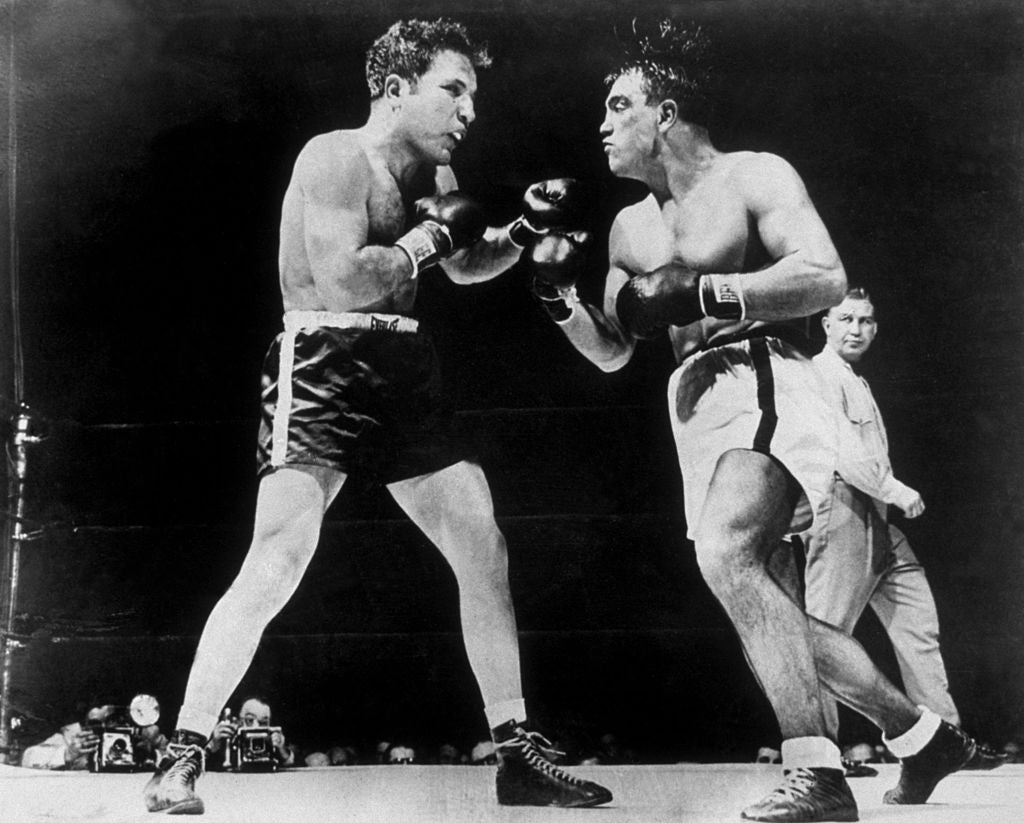

In 1942, LaMotta had his first fight with Robinson, losing on points over 10 rounds in New York. When the pair met again, in Detroit in February 1943, it was LaMotta who emerged victorious, knocking Robinson through the ropes in the eighth round to take the decision, and so inflict Robinson’s first defeat as a professional.

Their rivalry continued three weeks later, with Robinson surviving another knockdown by LaMotta to win on points, an outcome repeated in their next two encounters, in February and September of 1945. A bemused Robinson, the matador to LaMotta’s bull, once commented: “This guy, you just hit him with everything and he’d just act like you’re crazy.” As for LaMotta, he joked: “I fought Sugar Ray so many times it’s a wonder I don’t have diabetes.”

By 1947, LaMotta had been widely regarded as the leading middleweight contender for almost four years, having overcome such rugged opponents as former welterweight champion Fritzie Zivic, Bob Satterfield, Holman Williams, Tommy Bell, and Tony Janiro. During this time, LaMotta had bravely and consistently resisted the overtures of the criminal element then running the sport, with the result that it seemed as if he might never fight for the title that was his sole ambition. Finally, however, he bowed to the inevitable, and accepted an offer from mobster Frank “Blinky” Palermo to throw his November 1947 bout with Billy Fox in return for a title opportunity.

When the normally indestructible LaMotta was stopped by Fox, an investigation was immediately ordered. Although nothing was proved against LaMotta, he was fined $1,000 and suspended for seven months for concealing an injury be had rather fortuitously sustained in sparring prior to the bout. But on 16 June 1949, LaMotta finally realised his ambition when he was matched against the champion Marcel Cerdan in Detroit. After nine gruelling rounds, the Frenchman was unable to continue, claiming a damaged shoulder, and LaMotta was declared middleweight champion of the world.

That night, as the fighter celebrated in his hotel, he was congratulated by a man whom he had good cause to remember. It was the Bronx street bookie, still scarred by the beating he had received but most definitely alive. As LaMotta later recalled, “Two things happened to me that night. I won the championship of the world and I find out I’m not a murderer. Now right after that I could never fight any more. I didn’t realise it then but I lost the desire.”

Nonetheless LaMotta fought on, making two successful defences of his hard-won title. The first was to have been a return with Cerdan but the former champion was killed when his plane crashed in the Azores en route to New York. A match with Rocky Graziano was then cancelled when Graziano was injured in training. On 16 July 1950, LaMotta outpointed the European champion Tiberio Mitri in New York, and on 13 September of that year, in Detroit, he staged one of the great finishes in boxing history when, trailing badly on points, he managed to stop the Frenchman Laurent Dauthuille (to whom he had previously lost) with only 13 seconds remaining in the 15th round.

LaMotta’s last defence was against his old rival “Sugar” Ray Robinson in Chicago on 14 February 1951. Drained by his efforts to make the weight, LaMotta was soundly beaten in what was inevitably known as “the St Valentine’s Day Massacre”, the referee stepping in to save the champion from further punishment in the 13th round. LaMotta’s sole satisfaction from this his sixth and final clash with Robinson was that he ended the fight on his feet.

LaMotta continued fighting, now as a light-heavyweight, but without much success. In 1952, he suffered the indignity of being knocked to the canvas for the first time by Danny Nardico, and two years later, after a points loss to Billy Kilgore in Miami, LaMotta retired from the ring with a record of 83 wins, four draws and 19 losses. He subsequently opened a nightclub in Miami but his growing fondness for drink mitigated against its success. In 1956, he was jailed for six months when a teenage prostitute cited his premises as a place of assignation.

After his release, Rocky Graziano managed to arrange a few television appearances for LaMotta, who began to give serious thought to becoming an actor. After testifying about the Billy Fox bout before the Kefauver Senate investigation into boxing corruption in 1960, LaMotta appeared as a bartender in The Hustler (1961) before playing in some obscure film productions throughout the 1960s. In 1970, LaMotta co-wrote an autobiography entitled Raging Bull: My Story, which later served as the basis for Martin Scorsese’s 1980 film Raging Bull, with Robert De Niro as LaMotta.

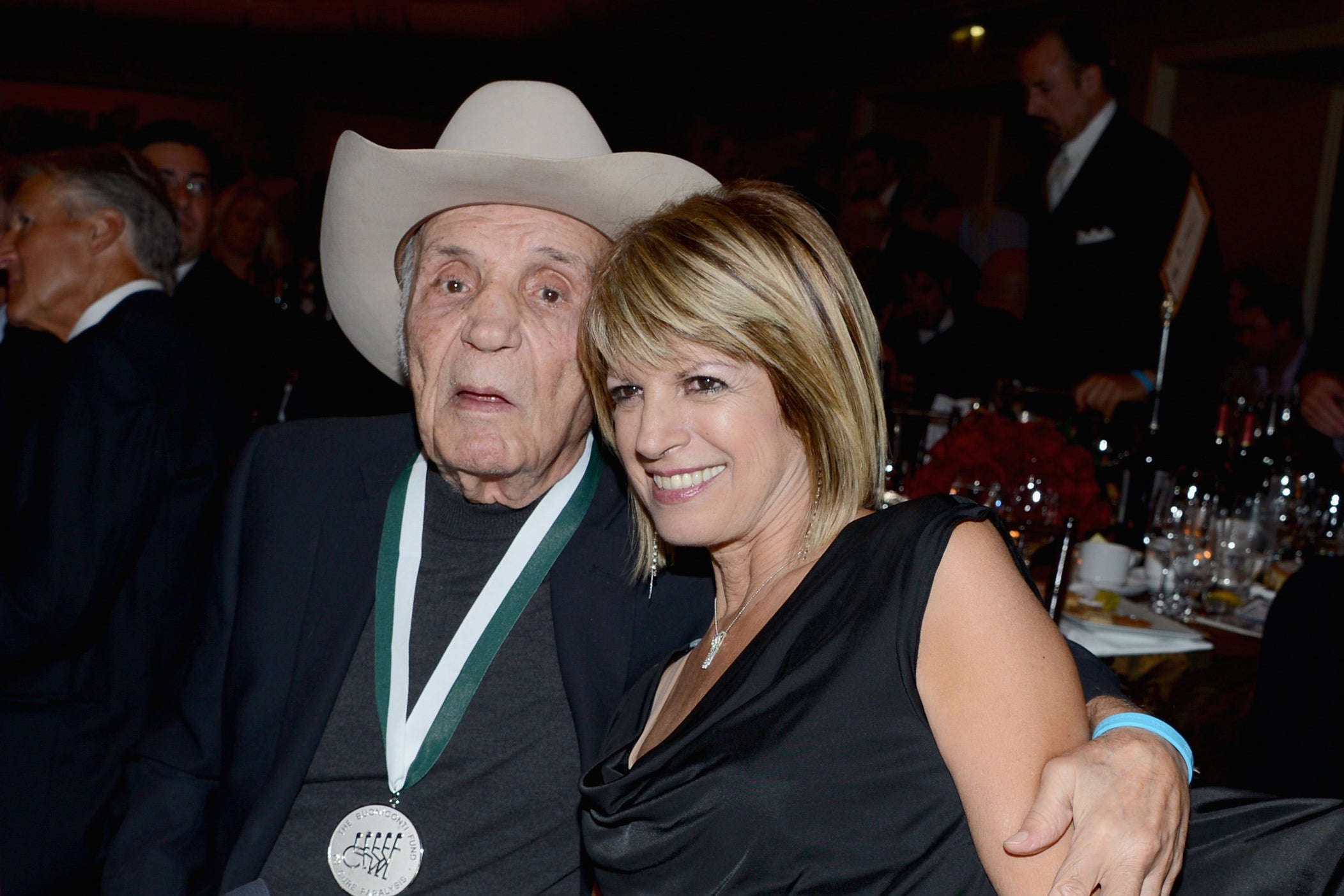

While LaMotta’s personal feelings on being portrayed as “a man without any redeeming features at all” in this critically acclaimed though relentlessly unpleasant (and not particularly accurate) film remain a matter of conjecture, he managed to turn the attendant publicity to his advantage, becoming a sought-after speaker on the nightclub and after-dinner circuit. Married and divorced on six occasions, Jake LaMotta was predeceased by both his sons: Jack, who died of cancer, and Joe, who was killed in air crash off Nova Scotia in 1998.

If LaMotta’s conduct outside the ring was frequently reprehensible – he was once described in print as “probably the most detested man of his generation”, and in addition to his criminal activity was also a self-confessed wife-beater and rapist – he nonetheless deserved his hard-earned reputation as one of the fight game’s bravest and most determined survivors.

Jake (Giacobe) LaMotta, boxer, born 10 July 1921, died 19 September 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments