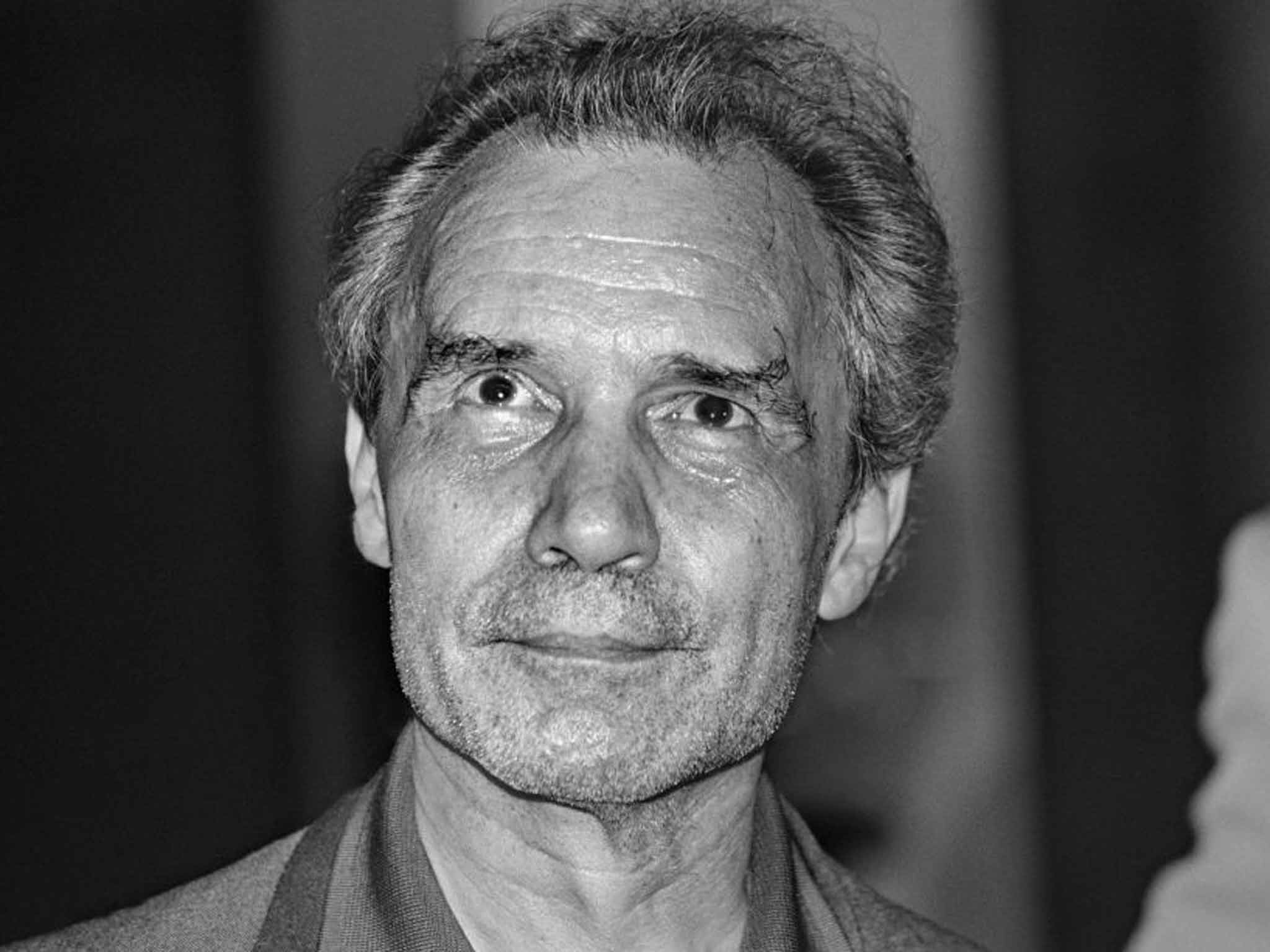

Jacques Rivette: Pioneer of the French New Wave who was acclaimed for his experimental and uncompromising work

He was known as an incisive critic, championing US films and European art-house and excoriating the older generation of French directors

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Critic-turned-director Jacques Rivette, pioneer of the French New Wave, was its least public face. His films are notable for their improvisatory theatricality, unconventional narratives, fantasy elements, interest in female friendship, mystery and conspiracy, documentary-style shooting, long scenes and extreme length.

Many approach three hours, and the Balzacian epic Out 1 lasts almost 13. His reliance on improvisation means that his films are suspended between control and freedom, and rely on all the participants' constant involvement and sensitivity to what is happening and what might happen, and he developed a set of regular collaborators who could fulfil these demands.

Rivette was born to a family of artistically inclined pharmacists. Cocteau's account of filming La belle et la bête inspired Rivette and he moved to Paris where he made Le Quadrille, a 40-minute film which one critic described as being “about what happens when nothing happens.”

Nominally a student, Rivette spent much of his time at the Cinémathèque Français, occupying the front row with Godard, Truffaut and other members of the nascent New Wave. He quickly became known as an incisive critic, championing US films and European art-house and excoriating the older generation of French directors. Intimidatingly ascetic, he held a strange power over his friends: even Godard would change his opinion to agree with him.

In Le coup du berger (“Fool's Mate”), Rivette's narration describes a wife's affair as a game of chess. It was an inspiration for what would become known as the New Wave. In 1958 Rivette started Paris nous appartient (“Paris Belongs to Us”), whose complex plot kicked off from a failed staging of Pericles, but it was heavily delayed until Chabrol and Truffaut bankrolled its completion in 1961.

Rivette next planned an adaptation of Diderot's La religieuse (“The Nun”), but when funding evaporated he and Godard staged it with Godard's wife, Anna Karina. As editor of Cahiers du Cinéma, Rivette transformed it into a Marxist culture journal, and he would play a major part in the events of 1968 following the state's dismissal of Henri Langlois, director of the Cinémathèque Française.

In 1967 he returned to film La religieuse (1967) but it caused a huge ruckus involving the Catholic Church, the Ministries of Information and Culture and, eventually, President de Gaulle. The controversy made it a hit. Rivette abandoned another historical story, leaving The Taking of Power by Louis XIV to Rossellini, while he produced a long TV documentary about his fellow director, Renoir.

The following year Rivette made L'amour fou, a multi-layered story of a marital breakdown in a theatre company during rehearsals for Racine's Andromaque. The production, rehearsals and back-stage action were filmed by different crews on different film formats to emphasis their different worlds.

It was also preparation for Rivette's masterpiece, Out 1, in which two theatre groups prepare Aeschylus productions. During its Balzacian 12 hours and 40 minutes it explicitly refers to “L'histoire de treize” from La comedie humaine, but the spin-off mysteries embrace Carroll's The Hunting of the Snark. Astonishingly it was shot in six weeks thanks to Rivette's long takes, though they were broken up in editing with cutaways or flashbacks. He set up a tension between “drama” and “documentary” by embracing mistakes like fluffed lines or the intrusions of the public into set pieces.

Still, exhibition was a challenge and he produced a “short” version, Out 1: Spectre a mere four hours long. The full version has been shown only a few times in cinemas but was recently released on DVD. Celine and Julie va en bateau (“Celine and Julie Go Boating”, 1973) is a similarly wide-ranging, surreal Alice in Wonderland-type story embracing theatre, magic, mysteries, conspiracies and identity swaps in a way that would inspire David Lynch.

Surreal fantasy and female friendship were increasingly prominent in films like Duelle (1976) featuring a battle between the Queen of the Sun and the Queen of the Night, and Noroît, a loose adaptation of Middleton's Revenger's Tragedy. These were the first two parts of an ambitious tetralogy, but the strain proved too great and Rivette had a breakdown three days into shooting the third, L'histoire de Marie et Julien, with Albert Finney and Leslie Caron.

This, and the fair-to-middling financial performance of many of his films meant that the 1980s were a difficult period. L'amour par terre (“Love on the Ground”, 1984) and La bande des quatre (“Gang of Four”, 1988) continued his investigations into theatrical troupes, while Hurlevent (1985), an adaptation of Wuthering Heights, was a change in style to simple realism.

La belle noiseuse (“The Beautiful Troublemaker”, 1991) based on Balzac's Le Chef-d'œuvre inconnu (“The Unknown Masterpiece”), brought another success as Michel Piccoli's blocked artist rediscovers inspiration by painting the nude Emmanuel Béart. Again, Rivette produced two versions: the full four-hour cut and a two-hour “Divertimento”.

In 1994 Rivette moved again away from his accustomed multi-layered narratives to produce Jean la pucelle (“Joan the Maiden”, starring Sandra Bonnaire. A searing five-and-a-half hour two part biography of Joan of Arc, it is stripped of artificiality. But it was not a success and, faced with another loss-maker, Rivette quickly made Haut bas fragile (“Up Down, Fragile”, 1995) a light-hearted musical with hidden depths. He followed this tangential homage to American cinema with Secret Défence (“Top Secret”, 1988). a sort of screwball mystery.

Va savoir (“Who Knows?”, 2001) found Rivette back on home turf: a mystery in a theatrical milieu. Two years later he returned to L'histoire de Marie et Julien, this time with Emmanuel Béart and Jerzy Radziwilowicz. Balzac was again the source, for Ne touchez pas la hache (The Duchess of Langeais, 2007). His final film was the relatively simple – and surprisingly short – 36 vues du Pic Saint-Lup (Around a Small Mountain, 2009).

His career was halted by Alzheimer's and shortly thereafter he married his partner, Véronique Manniez.

Jacques Pierre Louis Rivette, film director and film critic: born Rouen 1 March 1928; married firstly Marilu Parolini (marriage dissolved), secondly Véronique Manniez; died Paris 29 January 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments