Issey Miyake: Designer and fashion’s prince of pleats

One of the first Japanese designers to show in Paris, the maverick drew acclaim for his fusion of Eastern and Western influences and his experimentation materials

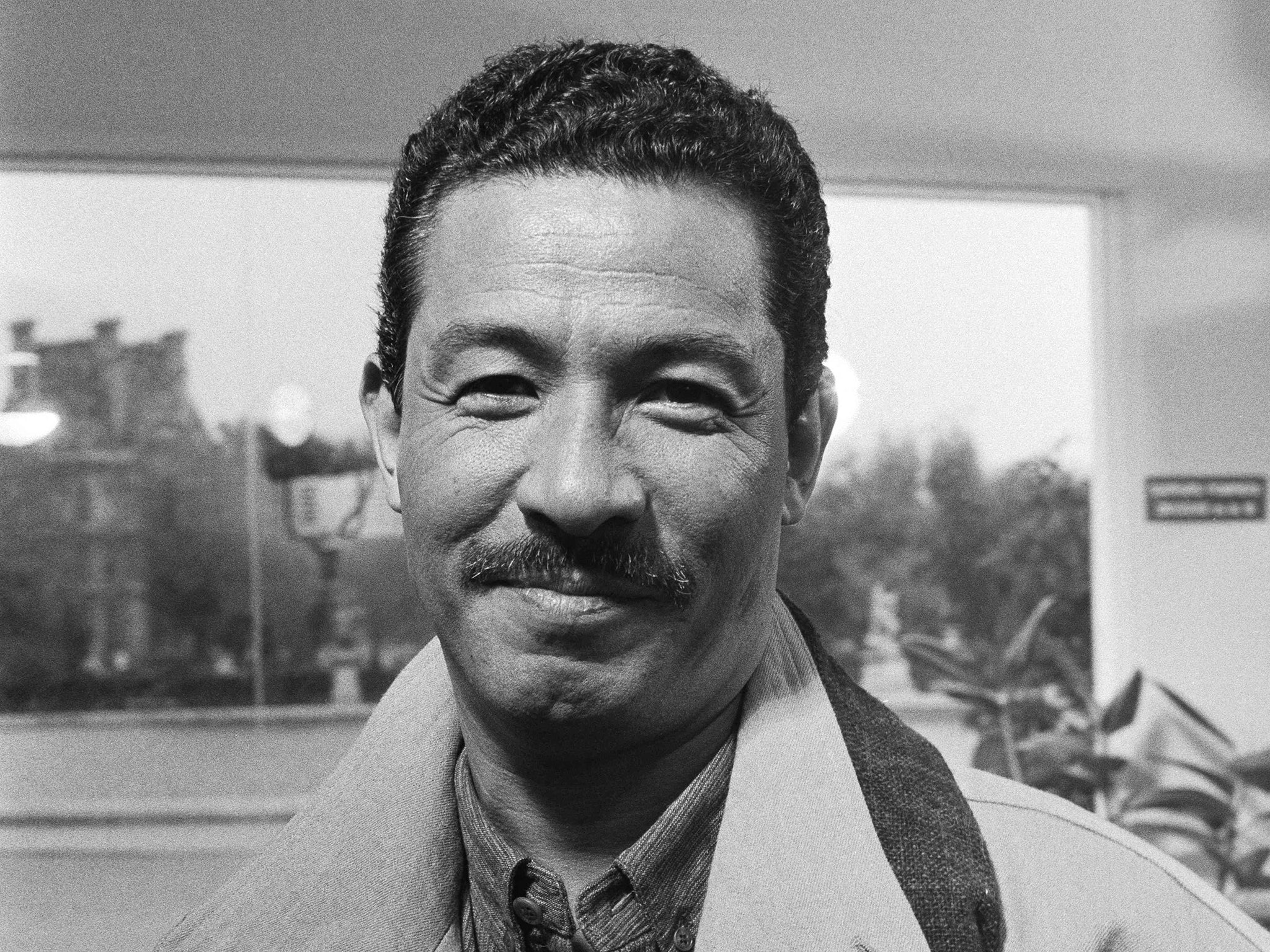

Issey Miyake, a Japanese fashion designer who became known as the prince of pleats and was widely admired for his bold style and innovative cuts, has died aged 84.

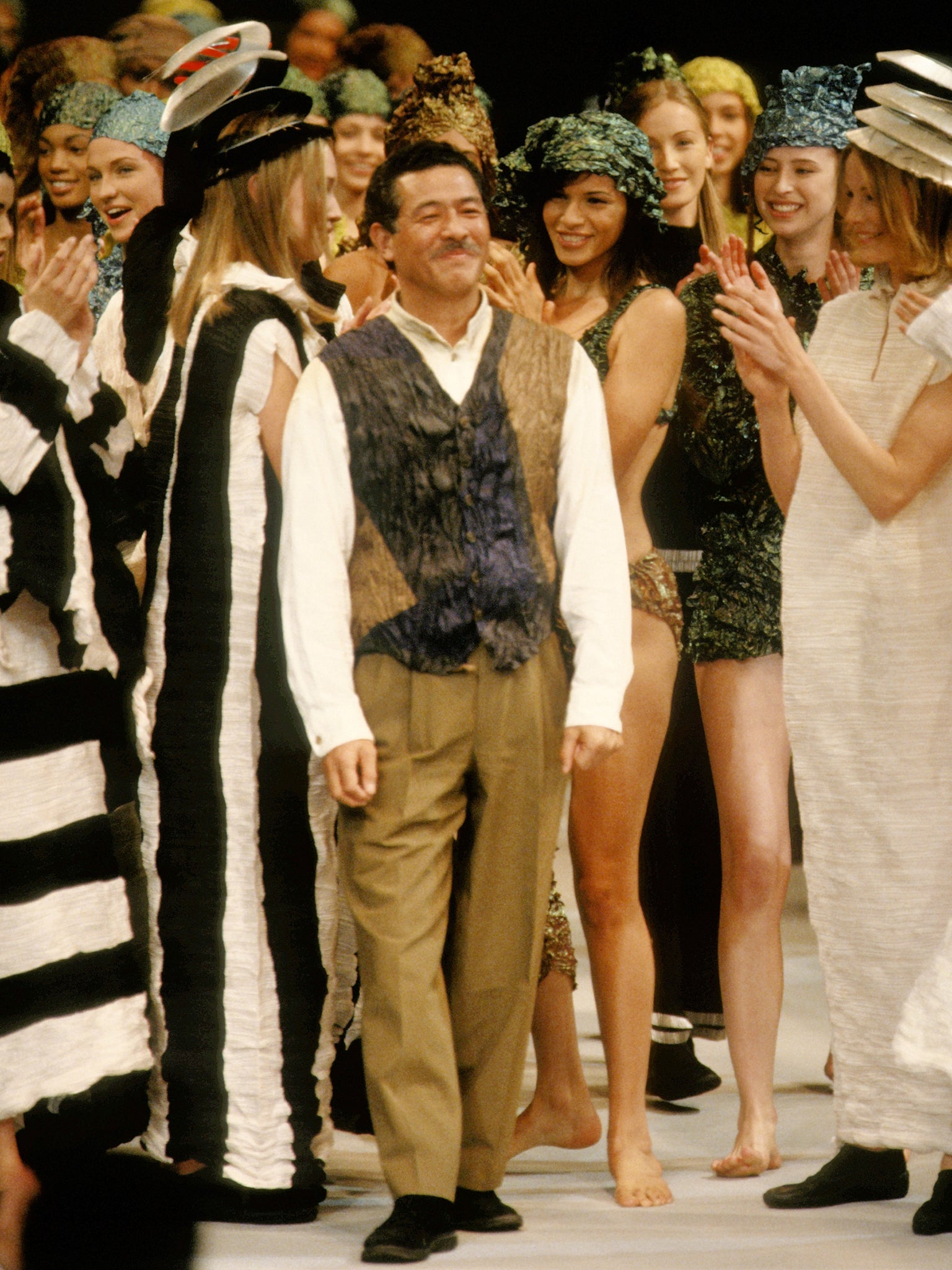

Soon after he launched his design studio in 1970, Miyake rose to stardom in the fashion world, drawing wide acclaim for his fusion of Eastern and Western influences and his experimentation with natural and synthetic materials. He was known best for his pleated clothing, which resisted wrinkles and evoked traditional origami, as well as for making the black turtlenecks that became a sartorial signature of Apple co-founder Steve Jobs.

Working at times with unusual materials – plastic, paper, wire, jute, foil, yarn – Miyake designed free-flowing garments as well as handbags, watches and fragrances that bore his name. His clothes weren’t form-fitting like those of his Western counterparts – he championed freedom of movement and often began his sleek designs with a single piece of cloth. His garments were frequently made with minimal decoration and detail, in sweeping shapes and block colours.

“To me, clothes should not be things which confine or enclose the body ... Clothes should make one free and feel like being oneself,” he said in a 1988 lecture at Rutgers University. “I think they are one of the best ways of expressing the liberation of the body and the mind. Maybe I make tools. People buy the clothes and the clothes become tools for the wearer’s creativity.”

His designs have been worn by a multitude of celebrities and displayed at museums around the world. There are 136 Miyake stores in Japan and nearly as many others worldwide.

Miyake was born Kazumaru Miyake in Hiroshima, Japan, on 22 April 1938. He was seven when the US dropped an atomic bomb on the city in 1945 at the close of the Second World War, killing tens of thousands of people and leading to the deaths of many others. His mother died of radiation poisoning three years later.

For decades, Miyake avoided discussing the attack, saying he preferred “to think of things that can be created, not destroyed”. But in 2009 he reflected on the bombing in an op-ed for The New York Times, urging President Barack Obama to visit Hiroshima and commemorate its victims.

“When I close my eyes, I still see things no one should ever experience: a bright red light, the black cloud soon after, people running in every direction trying desperately to escape – I remember it all,” Miyake wrote.

“I did not want to be labelled ‘the designer who survived the atomic bomb,’ and therefore I have always avoided questions about Hiroshima,” he added. “They made me uncomfortable. But now I realise it is a subject that must be discussed if we are ever to rid the world of nuclear weapons.”

Miyake studied graphic design at Tama Art University in Tokyo and later went to Paris, where he worked as an apprentice for designers Hubert de Givenchy and Guy Laroche. He also witnessed the student occupations and general strikes of May 1968, an experience that inspired him to design clothing for “the many rather than for the few”, as he put it.

He worked in New York before returning to Japan in 1969 to launch his own studio, and he soon became one of the first Japanese designers to show in Paris.

By the early 1980s, Miyake had started designing corporate uniforms, including a nylon jacket with detachable sleeves for employees at Sony. According to Walter Isaacson’s 2011 book Steve Jobs, the Apple executive sought something similar for his staff. That idea was quickly dismissed by employees, but Jobs became friends with Miyake and took to wearing the designer’s black turtlenecks, often pairing them with stiff blue jeans and white sneakers.

“He made me like a hundred of them,” Jobs told Isaacson, showing off a stack of turtlenecks in his wardrobe. “I have enough to last for the rest of my life.” Jobs died in 2011.

Miyake was deeply private, and no information on survivors was immediately available. In interviews, he often said that he tried to look toward the future in his work.

“All I can do is to keep experimenting, keep developing my thoughts further,” he said in 1998. “Certain people think that the definition of design is the beauty or the useful, but in my own work, I want to integrate feelings, emotion. You have to put life into it.”

The Washington Post’s Harrison Smith contributed to this report

© The Washington Post