Ian Holm: Versatile actor whose measured, gritty performances took him from Shakespeare to Hollywood

He was a key player in what emerged as the RSC’s finest hour of the 1960s, and would later win the hearts of Tolkien fans across the world with his turn as Bilbo Baggins

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“I’m still here,” is a line belted out by an ex-chorus girl in Stephen Sondheim’s Follies, but long before that show it was a defiant assertion from Max, the redoubtable patriarch of Harold Pinter’s The Homecoming. And it was certainly a resonant claim as roared by Sir Ian Holm in that role in a revival of the play in 2001, one of a handful of extraordinary “comeback” performances at the turn of the century after a period of almost 20 years of virtual disappearance from the stage following a traumatic breakdown in 1976, and nearly 30 years since his first, and unforgettable, RSC and Broadway appearances in the premiere of The Homecoming when he played Teddy, the dangerous pimping son of Pinter’s male household.

Holm’s ancestry was Scottish – a Glasgow-born father and mother from an established Edinburgh dynasty – although he was born in Goodmayes, near Ilford, Essex, where his father worked. His mother belonged to the Scottish family which owned the White Horse whisky business, and it was that name which Holm adopted when he went on the stage.

Most of Holm’s early life was spent in the shadow of his brother, the elder by 10 years (Holm’s mother was nearly 40 when he was born), and he was miserable at a Chigwell school he described as “horrible – and I didn’t learn a thing”. His childhood introspection increased, at the age of 12, when his brother died.

The family had moved to Worthing and it was in the repressively grey, post-war respectability of that town, bleakly recalled in Wish You Were Here onscreen, that Holm’s love of the cinema was cradled. On his own a great deal in his formative years, he was a regular in the stalls of the Dome in Worthing, watching virtually all the major movies of golden ages for both Hollywood and British cinema; he retained a lifelong affection for the early favourite of the Charles Laughton version of Les Miserables.

Holm said himself that it was “a desire to be noticed”, particularly after his brother’s death and to overcome his increasing introspection, which crystallised his desire to become an actor. He began his Rada training before his national service, spent mostly as a lance-corporal in the Royal Army Service Corps. (“It was Dad’s Army really... I never saw a gun.”)

After returning to Rada to complete his training, almost immediately he auditioned successfully for the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon – a theatre with which he would be associated for the bulk of his early career – and joined the company during the 1954 season. They were lowly beginnings – Holm was contracted as the proverbial spear-carrier and to understudy in that season’s Othello with Anthony Quayle, then the Memorial Theatre’s director and a shrewd talent-spotter, both directing and playing the title role.

Quayle noticed Holm’s quiet dedication and he also came to admire, watching a few understudy rehearsals, the unshowy, gritty honesty of his acting, which was to be constant throughout his career. Holm was invited back for the whole of the following season which had Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, then at the very height of their joint fame, at the head of the company. More substantial 1955 roles included Donalbain in the Oliviers’ Macbeth and Mutinus in Peter Brook’s revelatory production (which he also designed and composed) of the rarity of Titus Andronicus, with Olivier’s astonishing reclamation of an allegedly unplayable role. He returned to this production – after a six-month stint in provincial rep (back in Worthing, as it happened) playing a string of character parts in plays from Agatha Christie to Shaw – for its triumphant European tour of 1957 and a London season.

Michael Redgrave had been lured back to Stratford by Quayle for the 1957 season and Holm’s performances included a delightfully befuddled Verges in a Much Ado About Nothing, ravishingly set in 1870s Italy, with Redgrave and Googie Withers as Benedick and Beatrice, Peter in Romeo and Juliet and a strikingly grave Sebastian (convincingly Dorothy Tutin’s twin) in Twelfth Night. He also helped Quayle out by agreeing to understudy Redgrave giving his second (and last) Hamlet, a multilayered and always fascinating performance which Holm admired deeply and watched often from the wings (although, at 5ft 6in to Redgrave’s 6ft 4in he was in some measure glad that he never had to go on).

With his commitment to Stratford and ensemble theatre, Holm was a natural early choice as a member when the Royal Shakespeare Company was formed, reconstituting the Memorial Theatre operation and with a London base at the Aldwych, under Peter Hall in 1961.

For most of the 1960s, Holm was a mainstay of the RSC as it built up its ensemble style over a period which some would claim saw the strongest blossoming of its company ideal. At the Aldwych in 1961 alone, he was happy to play supporting roles – First Judge in Giraudoux’ aqueous whimsy Ondine with Leslie Caron, and Mannoury in John Whiting’s The Devils with Tutin’s memorable Sister Jeanne – as well as more significant opportunities such as Trofimov in The Cherry Orchard. Directed by Michel Saint-Denis, this production did not perhaps quite match the level of Saint-Denis’s legendary pre-war Three Sisters, but Holm’s nervy, pallidly underfed-looking (he had the protean ability to change his shape at will of some of the greatest character-actors) eternal student stood out even in a lustrous company including Sir John Gielgud, Ashcroft, Tutin and Judi Dench.

Stratford saw him back to repeat both Puck and Gremio (1961) before a major performance in Peter Hall’s “sandpit”-set production of Troilus and Cressida (Aldwych, 1962). He and Tutin packed a powerful sexual charge in their scenes together and Holm coped superbly with the challenges of the complex, clotted speeches of disgust and despair which follow Troilus’s witnessing of Cressida’s betrayal in the Greek camp; this was volatile and dangerously immediate emotional acting.

Inevitably Holm was a key player in what emerged as the RSC’s finest hour of the 1960s – the cycle of The Wars of the Roses (1963-64), a thrillingly revisionist reevaluation of the history plays (tracing the monarchy from Edward IV through to Richard III in John Barton’s canny arrangement) and of Shakespeare’s notions of kingship. Against John Bury’s epic steel-clad set, Hall’s productions were studded with major performances – Ashcroft’s Margaret of Anjou, Donald Sinden’s Duke of York included – and Holm was in wonderful form as he traced Gloucester’s emerging evil into a coolly monstrous Richard III.

Another extraordinarily strong cast – the RSC at concert-pitch – appeared in Hall’s production of Pinter’s The Homecoming (1965), set in Bury’s cavernous, chalky north London room with Holm as the cold-eyed, spivvy Lenny, ferally circling the incoming wife (Vivien Merchant) of the returned prodigal son (Michael Bryant). He made an equally strong impact when the production opened on Broadway (Music Box, 1967), winning a Tony Award for Best Supporting Performance.

His Romeo at Stratford (1970) on his return was a disappointment, and he left for a time – wisely – to recharge his acting batteries in modern work. Arnold Wester’s The Friends (Roundhouse, 1970), a sprawling evening in the author’s own production, offered him only a distinctly lacklustre role, and not even the full majestic panoply of an old-style HM Tennent production of Terence Rattigan’s A Bequest to the Nation (Haymarket, 1970) could rescue an awkward adaptation from a television script. Holm as Horatio Nelson did his best with an underwritten part, at his strongest in a touching scene in which the admiral tries to explain the strength of Emma Hamilton’s sexual appeal. More rewarding material came his way from Edward Bond with The Sea (Royal Court, 1973) in William Gaskill’s finely controlled production, and his comedic gifts were well served by Mike Stott’s Other People (Hampstead, 1974).

Back with the RSC and with a handsome revival of Shaw’s The Devil’s Disciple (Aldwych, 1976) behind him, expectations were running high for Holm’s appearance as Hickey, the marathon leading role of O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh (Aldwych, 1976). Rehearsals had gone well, but during an early preview Holm “cracked up” in mid-speech, left the stage and was found sobbing, curled up on his dressing-room floor. This was no temporary crise de nerfs; Holm described his breakdown later as “like someone pulling a curtain down”. He saw a psychiatrist, who explained that he was suffering from a chemical imbalance in the brain (clinical depression, in effect) as well as chronic fatigue – prior to Iceman rehearsals he had spent some four months on a parched desert location for Zeffirelli’s overblown Life of Jesus. He was put on medication which slowly readjusted the maladjustment.

But, with the one exception of an Uncle Vanya (Hampstead, 1979) with, at Holm’s insistence, his friend Nigel Hawthorne also in the cast as security – he got through safely enough, but it was hardly on a level with his best work, as he knew himself – he stayed away from the stage for nearly two decades.

There was, of course, no shortage of film or television work, his career having already included fine performances for Richard Attenborough in Oh, What A Lovely War (1969) as a slyly punctilious Poincaré in the opening sequence of world powers on Brighton Pier, and in Young Winston (1972).

With his dourly driven Scottish coach in Chariots of Fire (1981), for which he won both Cannes Festival and Bafta Awards for Best Supporting Actor, his stock rose considerably both at home and, following the success of Chariots in the USA, in Hollywood. He was an impressively icy android in Alien (1979) and an extremely touching, almost masochistically devoted old flame of Ruth Ellis in Dance With A Stranger (1985).

During the 1980s and 1990s he also often astonished with his range on television. A chilling Goebbels in The Third Reich, the schoolteacher (Andrew Crocker-Harris) in Rattigan’s The Browning Version, and the enchanting series of The Borrowers (with his third wife, Penelope Wilton), were all top-flight projects. But for many, perhaps his most striking small-screen performance will remain his JM Barrie in Andrew Birkin’s series of The Lost Boys.

In another study of emotional repression, Holm’s eloquent eyes throughout the series were a constant index to the inner landscape of a man who yearned for love but who could express it only obliquely. The portrayal – full of the most beautifully observed detail – was haunting in its gradual revelation of a frozen soul.

Then, just when the tag of being described as the greatest actor we never had (applied to Robert Stephens almost as often) was being heard of Holm more frequently, he returned to the theatre. He had previously said “If Harold Pinter writes a new play and if it has a part for me...’’ he would take the opportunity, and Pinter provided both play and leading role in Moonlight (Almeida, 1993).

This was Pinter’s return to full-length material and his first play for some time. Holm made a much welcomed and, happily, completely confident appearance as a dying husband (he spent virtually all evening in bed) trapped in a decaying marriage. Fully charged with a resonant accidie and beautifully phrasing a text of characteristically meticulous rhythms, the performance was more widely seen on its subsequent West End transfer (Comedy, 1993).

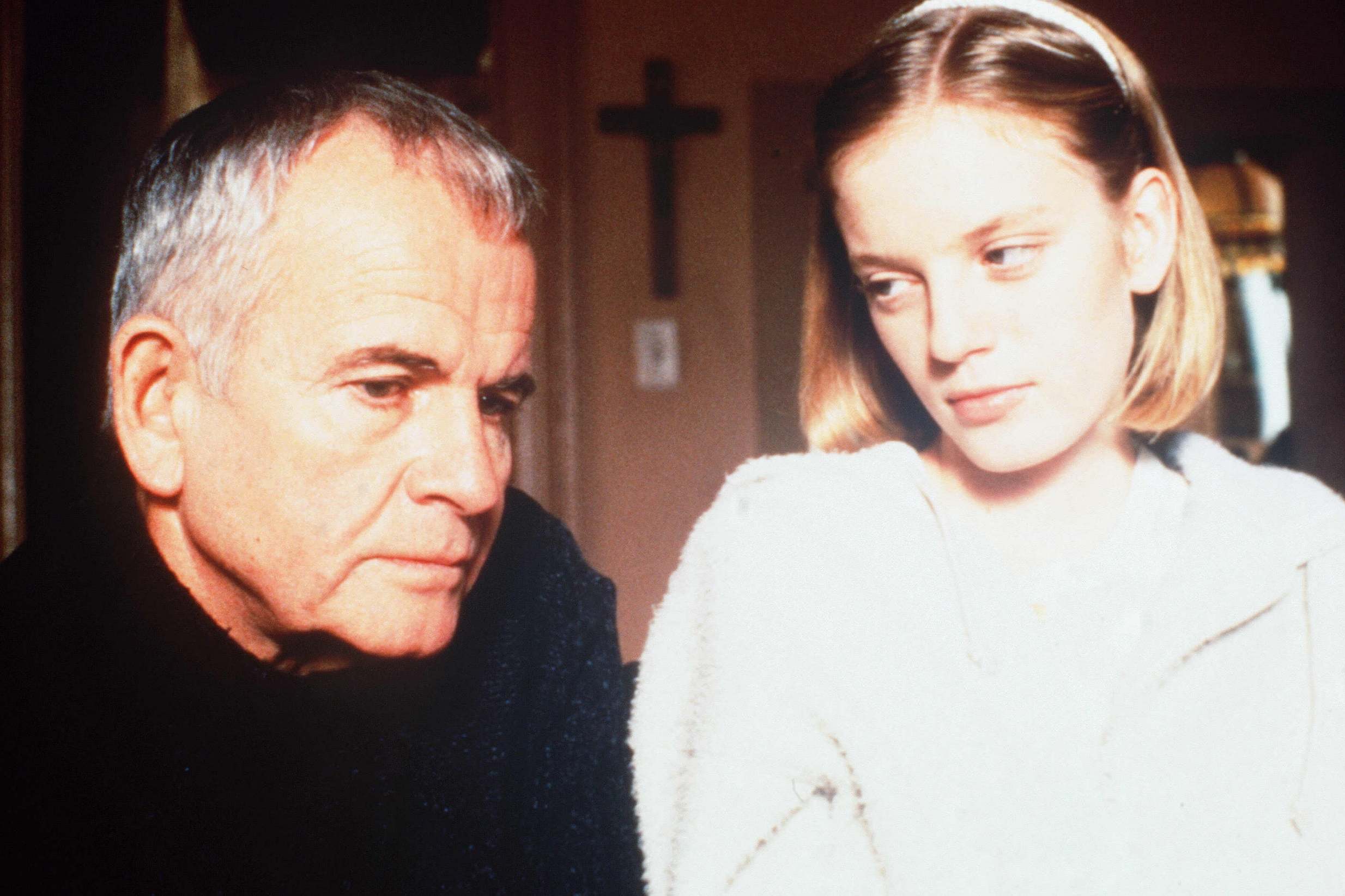

Throughout the 1990s Holm was in ever-increasing demand and took on a heavy movie workload. Subsequent films ranged from the bizarre – Luc Besson’s extravagant space fantasy The Fifth Element (1997) with Holm’s benign priest – to the less commercial but engrossing The Sweet Hereafter (1997), directed by Atom Egoyan. Adapted from Russell Banks’s novel, this saw Holm in what was effectively his first top-billed film starring role, and he burnt up the screen with his zealous, hectoring lawyer, determined to find justice for the parents of the children killed in a Canadian town in a schoolbus accident.

It began to seem as if Holm had become a kind of good-luck talisman for directors on offbeat films – Sydney Lumet cast him as an Irish cop from Queens (another spot-on accent) in Night Falls on Manhattan (1996), he played a splenetically funny patriarch (with Cameron Diaz as his daughter) in Danny Boyle’s A Life Less Ordinary (1997) and Stanley Tucci gave him a rich and beguiling part as a New York restaurateur in Big Night (1996).

Holm was, of course, virtually automatic casting – certainly for Tolkien anoraks – as Bilbo the hobbit who launches the Ring Cycle by giving his nephew Frodo (whom Holm had previously played in the BBC Radio version) the ring which could control Middle Earth in The Lord of the Rings (2001). In this hugely successful film he stood out even in a stellar cast and amid lavish special effects and unusually large amounts of false facial hair. He would return to the role of Bilbo in The Return of the King (2003), and as the older version of the character in The Hobbit film series of the 2010s.

In an interview with The Independent in 2004, Holm said he was “completely amazed” by the reaction to the Tolkien films. “I get a lot of fan mail addressed to Bilbo and sometimes Sir Bilbo – it’s hardly ever addressed to Ian Holm, in fact.”

In 2002, he was treated for prostate cancer and his work would become more sparse in his later years. Despite his increased prominence in Hollywood, Holm’s finest performances at the turn of the century were still on the stage.

In 1997 for Richard Eyre during a final South Bank season as director, he gave one of the best Lears – and, fittingly, given his earlier career, one of the best Shakespearean performances – in living memory. Played on a mostly bare traverse stage, giving unusual intimacy in the Cottesloe auditorium, Eyre’s scrupulous production was ideally shaped and scored to Holm’s basic humanity as an actor. Essentially domestic in initial approach – and drawing some wry, pugnacious comedy in the earlier family scenes – slowly both production and leading performance moved into the universal without strain, most powerfully in Lear’s scenes with Michael Bryant’s movingly clapped-out Fool, and, never to be forgotten, in his encounter on the heath with Edgar as “poor Tom”, both finally muddied and naked, revealed as poor forked animals. In Lear’s words, this was “the thing itself”.

In 2001, Holm returned to The Homecoming (Gate, Dublin), a play about which he had “proprietorial” feelings (he never went to see any other production). More than 30 years on, and just after his own 70th birthday, this time he played Max, the defiant, fading patriarch in a production very different from Hall’s in its focus on the play’s potent imagery and, if anything, even more shocking in a post-feminist era.

White-haired and shabbily cardigan-ed, inhabiting his chair like some stubborn mangy old bull, Holm extracted all the gleeful comedy in the part without losing the pathos of Max’s decline and looming usurpation. The portrayal confirmed Holm’s private theory that “Lenny is Max as a young man”. One wheel of Holm’s career had certainly come full circle.

Sir Ian Holm, actor, born 12 September 1931, died 19 June 2020

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments