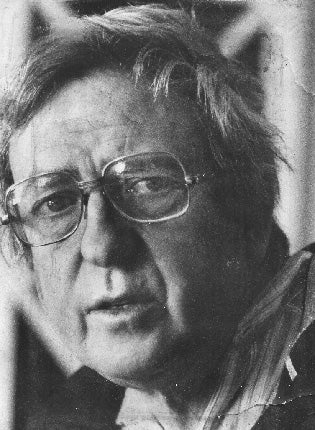

Ian Bowler: Engineer who laid an historic high-altitude oil pipeline between Iran and the Soviet Union

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Legendary oil and gas pipeline engineer, serious sailor, poet, short story writer, flamenco guitarist, naturalist, falconer, expert cook, raconteur and polymath: Ian Bowler was all of these.

His greatest achievement was getting a contract from the government of Iran to design and construct a gas pipeline from Ahwaz, near the Persian Gulf, to Astara, the Soviet border town on the Caspian. This high-pressure pipeline, completed in 1970 at a cost of $800m, was an outstanding technical and political achievement. It had taken four years from the signing of the contract to operation. Forty-two inches in diameter and 1260 kilometres long, with 10 compressor stations, a gas treatment plant and 800km of gathering pipelines from the surrounding oilfields, it pressed the limits of the current technology.

Nobody then had transmitted high-pressure gas at altitude, yet the pipe was laid over the Zagros mountains that run the length of Iran, in places 14,000 feet high. The pipe, of record dimensions, was produced in the Ahwaz pipe mill. Such were the skills developed by the Ahwazi welders that they were later employed in the North Sea. Nobody in the West had dealt with the Russians on such a project before; the Cold War was still on and Iran was a vital part of western strategic interest. It was for this that Bowler was awarded a Foreign Office CBE in 1971, to add to the OBE he had been awarded in 1957 for earlier projects.

Bowler was born in Northern Ireland, the son of an impoverished army officer. He started to work for Richard Costain as a quantity surveyor and during the war travelled round England building aerodromes for the RAF. In 1940 he married Betty Wardle, who ran a riding school in the Peak District.

In 1945 Costains sent him to work on oil terminals in the Persian Gulf. In 1948 the John Brown company bought out Costains to form Constructors John Brown to work on oil refineries and in 1954 CJB sent Bowler to Ahvaz, in south-western Iran, to work on the construction of an oil terminal and a number of sugar beet factories.

In 1958 they started work on an oil pipeline from Ahwaz to Tehran. In Iran Bowler met and married Laure, a Belgian, who was of great help in entertaining clients and officials from the ministries. As the pipeline moved north, the Bowlers moved to Shiraz, where they were introduced to more elevated Iranian social circles, which opened contractual doors for CJB.

Not long afterwards, at a large party in Tehran, across the room Bowler saw the striking Hamideh (Hamoush) Azodi, the twice-married daughter of Prince Yadollah Azodi, a distinguished Iranian diplomat and foreign minister. The next day Bowler sent her a lorry-load of roses with his card. She had no idea who he was at this stage, for they had not been introduced at the party, but she would later provide him with the high-level connections he needed.

Taking a number of his colleagues with him, he left CJB to set up the International Management and Engineering Group and married Hamoush. They made a glamorous pair on the glittering Tehran scene. It was a sign of Bowler's extraordinary skills as an engineer and negotiator that IMEG, a small company and unknown quantity, was awarded the contract for the mammoth IGAT gas pipeline. Eyebrows were raised, but the line was built to budget and on time. It was followed in 1977 by a second, larger pipeline which was nearly half-completed when work was stopped by the revolution, leaving IMEG owed vast sums by the National Iranian Gas Co.

Hamoush was part-heiress to a large estate at Shahrud in north-east Iran, at the southern foot of the Alborz mountains. Bowler loved escaping there to pursue rock partridge, snowcock and mouflon. He acquired two Saker falcons and in 1973 wrote The Predator Birds of Iran. He had the use of another refuge at Vali Abad, a disused royal hunting hut in the mountains nearer Tehran. Here he could take weekends off to be alone or to entertain more privately.

Bowler was also a sailor. He acquired the 54ft Bermudan ketch Tai-Mo-Shan, built in Hong Kong in 1933 by four Royal Navy officers from teak they found in the dockyard. Although a highly technical man, Bowler despised innovations at sea such as engines and radio navigation; wind, compass and sextant were all he needed. Once, off La Rochelle without an engine, he rescued a French yacht and towed it into port, for which he received a French honour. Later, with Bob du Jardin, a French colleague on the IGAT project, he embarked on a voyage gastronomique across the Atlantic. The logbook records dramas with weather and gear, but the biggest disaster it recorded was running out of mustard half-way across.

Bowler did not confine his interests to Iran. In 1969 he was involved with the conceptual design of the SUMED pipeline that followed the Suez canal, which was becoming too small for the new supertankers. IMEG designed and in 1984 built a technically challenging oil pipeline across the Andes in a dangerous part of Colombia. In spite of frequent sabotage, it is still carrying crude oil from Caño Limó*to the port of Covenas. Such was IMEG's technical reputation, the Iraqi government, which for political reasons had signed a pipeline contract with a Russian organisation which lacked the necessary competence, insisted that IMEG provide technical supervision.

In the late 1980s IMEG was involved in a number of pipeline projects in Malaysia. Bowler's commitment to conservation led him to persuade the authorities to bury the line in places so that wildlife, particularly elephants, would not be disturbed.

Bowler was attracted by challenge. After the break-up of the Soviet Union Bowler moved in to promote a number of projects ranging from the redevelopment of old oil and gas fields in the republics to designing new technology for pipelines across remote regions in freezing conditions.

These projects always demanded new technology. He was far ahead of his time and these projects, such as the Baku-Ceyhan line, have only just begun to see the light of day. Wherever he went he had a great gift for cultivating friendships with the men and women on the spot, who were all charmed by his bonhomie and gift for lively and entertaining conversation.

As a young man, Bowler had been much influenced by John Fothergill, proprietor of the famous Spread Eagle at Thame and author of An Innkeeper's Diary, and before the war Bowler went to live with him to decide whether or not to become a poet. Fothergill's links with the literary and artistic figures of the day, his erudition, wit, culinary skill and his love of sparkling conversation all rubbed off on Bowler. Bowler wrote good poems all his life, addressed to many of the women that he loved, and composed exquisitely turned short stories inspired by the many unusual characters he had come across. He surrounded himself only with beautiful objects, many acquired from the antique dealers of Tehran. He was inspired by a friend of Julian Bream to learn classical guitar. This turned into a love of flamenco guitar. He became so good at this that when in Spain he was invited to take the floor.

A man of great ideas, Bowler was not, in the end, a commercial success. By the end of his life, the fortune that he had made from the IGAT pipeline had evaporated: everything had gone, even the splendid house he shared with Hamoush in Chelsea that had been Augustus John's studio. He kept the yacht Tai-Mo-Shan until the onset of Parkinson's prevented him from sailing her, even in a wheelchair. His last years were spent in straitened circumstances, being visited by a handful of friends and cared for by his last companion, Jane Coyle.

Antony Wynn

Ian John Bowler, gas and oil pipeline engineer: born 16 December 1920; OBE 1957, CBE 1971; married 1940 Betty Warwick (two daughters), secondly Laure, 1963 Hamideh (Hamoush) Azodi (one stepson, one stepdaughter); died 10 May 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments