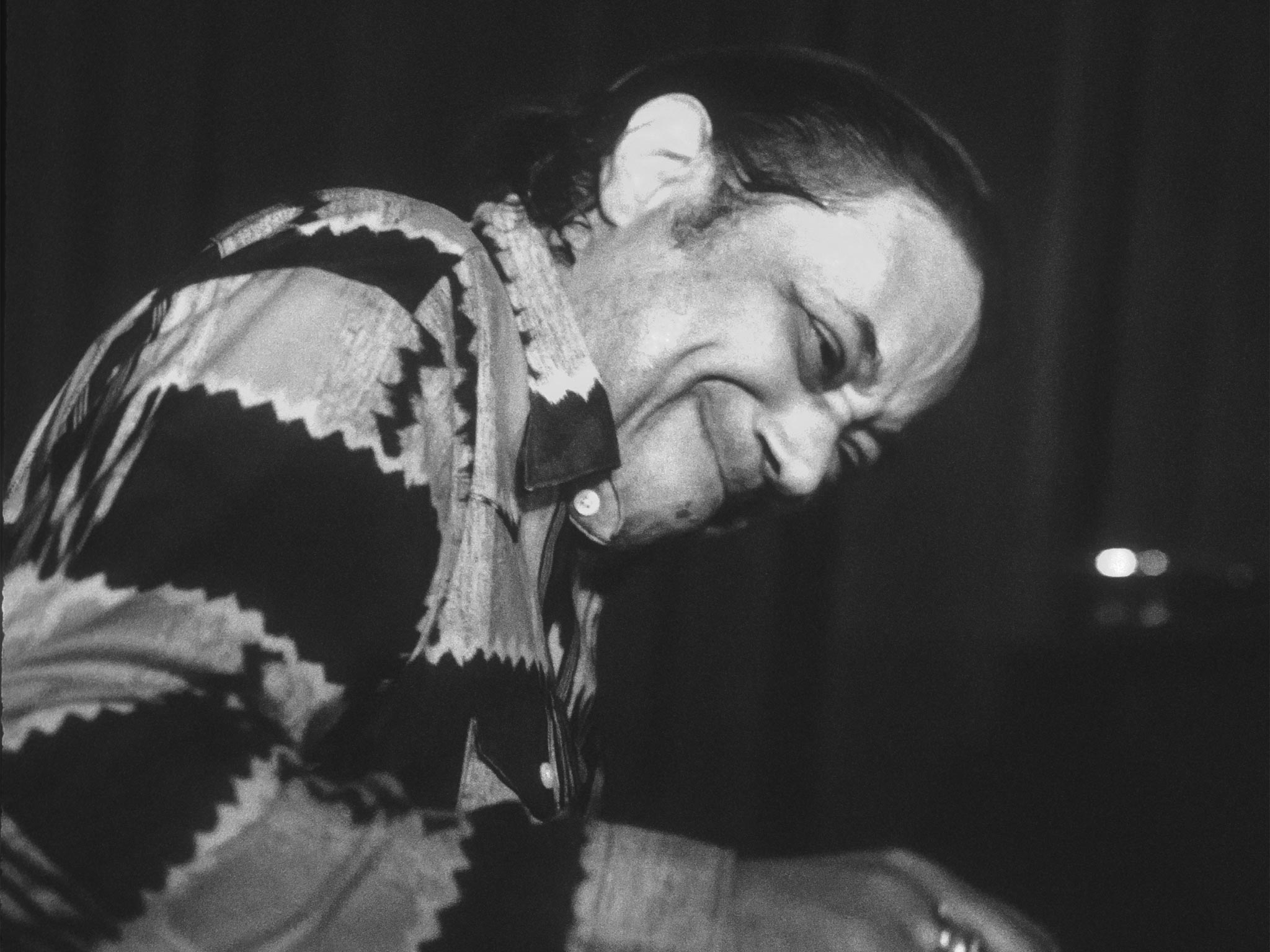

Horace Silver: Trailblazing jazz pianist, composer and bandleader who led the way with Art Blakey in developing the hard bop style

Jazz had become abstract, esoteric; Silver remained grounded in gospel and the blues

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Horace Silver was a trailblazing pianist and composer and a primary developer in the 1950s and 1960s of the style of jazz known as hard bop, marked by its catchy melodies and relentless rhythms. In 1953, Silver and drummer Art Blakey formed the hugely influential Jazz Messengers, and Silver’s earthy, blues-drenched compositions became a key part of the band’s repertoire and helped define a musical era.

“His work as a pianist, composer, and leader of quintets became pivotal in the jazz of the late Fifties,” the jazz historian Martin Williams wrote in his 1970 book The Jazz Tradition. When other jazz musicians were becoming more and more esoteric, reaching levels of musical abstraction where few listeners would follow, Silver remained grounded in gospel and the blues. His tunes were always hummable and toe-tappable. “They got so sophisticated that it seemed like they were afraid to play the blues, like it was demeaning to be funky,” Silver said in 1994, describing his populist approach. “And I tried to bring that. I didn’t do it consciously at first. But it started to happen.”

In dozens of recordings for Blue Note in the 1950s and ’60s, he combined long-standing traditions with the harmonic advances of bebop, the intricate style introduced in the 1940s by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. Silver’s music sounded casual and spontaneous, but it was carefully composed and arranged, with riffing horn parts and room for solos.

His easily recognisable but hard-to-classify music led critics on a search for a proper term to describe it. They called it “soul jazz” and “funk” before settling on hard bop. “Horace Silver’s music has always represented what jazz musicians preach but don’t necessarily practice, and that’s simplicity,” the Grammy Award-winning bass player Christian McBride said. “It gets in your blood easily. You can comprehend it easily. It’s very rooted, very soulful.”

Many of Silver’s tunes, the likes of “Nica’s Dream”, “Doodlin’”, “Señor Blues” and “Filthy McNasty”, have become standards, recorded hundreds of times. His music also found popularity beyond the world of jazz, and his 1964 “Song for My Father,” became a minor pop hit. The Brazilian-influenced, loping bass line was borrowed wholesale by Steely Dan for their 1974 hit “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number”.

His compositions alone would put Silver in the front rank of jazz history, but he was also an important bandleader who helped propel the careers of dozens of major musicians, including trumpeter Art Farmer and saxophonist Joe Henderson. As a pianist he was known for his raw, impassioned performances, as sweat dripped from his face and his hair whipped in the air. With his left hand he punched out a driving bass line that kept the pulse moving while he improvised infectiously melodic solos that danced above a solid rhythmic framework.

“I dreamed my dreams of becoming a great and famous musician, playing and travelling all over the world,” he wrote in his 2006 autobiography Let’s Get to the Nitty Gritty. “I said to myself, ‘One of these days, I’m going to make records. And when the people put the needle down on the record and play, about of a quarter of an inch in, they will say, ‘That’s Horace Silver – I recognize his style.’”

Horace Ward Silver was born in 1928, in Norwalk, Connecticut. His father was from Cape Verde, then a Portuguese colony off Africa’s west coast, and had anglicised his name from Silva. His mother, who died when he was nine, introduced him to gospel music at a Methodist church. His father was an amateur musician who played Cape Verdean folk songs.

Silver studied piano and began his professional career in Connecticut as a saxophonist before returning to the piano. In 1950 the saxophonist Stan Getz heard him at a Hartford jazz club and invited him to join his band.

After moving to New York, Silver performed with an array of stars, including saxists Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins and young trumpeters Miles Davis and Clifford Brown, who was an early member of the Jazz Messengers. Brown and Silver appeared on the 1954 three-volume A Night at Birdland, which featured several of Silver’s compositions and went a long way toward defining the hard-bop style.

After leaving the Jazz Messengers, Silver recorded celebrated albums including Six Pieces of Silver (1956), Blowin’ the Blues Away (1959), The Cape Verdean Blues (1965) and The Jody Grind (1966). He moved to California in the 1970s and explored various spiritual paths, which were reflected in his music at the time.

In the 1990s he had a late-career renaissance with well-received albums that returned to the style he had pioneered in the 1950s. He was named a jazz master by the US National Endowment for the Arts in 1995, and was one of the last three survivors of Art Kane’s famed “Great Day in Harlem” photograph for Esquire in 1958. The others are Benny Golson and Sonny Rollins.

“We don’t have any Charlie Parkers on the scene, or Art Tatums or Miles or Dizzies, as far as I’ve seen,” Silver said in 1996 after a film about the photo was released. “These guys are gone, and they haven’t been replaced with anyone of that calibre... Those with style will be remembered.”

Horace Ward Martin Tavares Silver, musician: born Norwalk, Connecticut 2 September 1928; married Barbara Dove (one son); died New Rochelle, New York 18 June 2014.

© The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments